by Lawrence Wittner | Jan 25, 2026 | Global Justice, Peace

There is a widening gap today between global possibilities and global realities.

The global realities are quite grim.

Despite some advances in countering worldwide poverty, it remains at a startlingly high level. According to the World Bank, half of humanity lives on less than $6.85 per day per person, with over 700 million people living on less than $2.15 per day.

Moreover, economic inequality is vast and increasing. A recently-released World Inequality Report, produced in conjunction with the United Nations, found that, in almost every region of the world, the richest 1 percent is wealthier than the bottom 90 percent combined. Indeed, the richest 0.001 percent of the world’s population controls three times the wealth of the poorest half, and its wealth is growing at a faster rate.

As the charitable organization Oxfam has observed, there is no morally defensible justification for this state of affairs. “Extreme wealth is not accumulated simply as a reward for extreme talent,” it has noted. “The majority of billionaire wealth . . . is unearned, derived from inheritance, crony connections, and monopolistic power.” Moreover, billionaires and giant corporations are fostering greater economic inequality and misery by opposing labor laws and policies that benefit workers, undermining progressive taxation, employing modern colonial systems of wealth extraction in the Global South, and using monopoly power to control markets and set the rules and terms of exchange.

Furthermore, when it comes to respecting international law, the rulers of some powerful nations are behaving increasingly like gangsters.

Donald Trump is particularly flagrant in this regard. During his second term as President of the United States, he has already bombed seven nations (Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen), threatened to invade or seize five others (Canada, Colombia, Cuba, Greenland, and Mexico ), blown up 33 foreign boats and their sailors, kidnapped the president of a sovereign nation (Venezuela), and announced plans to “run” Venezuela and take control of its vast oil resources. “I don’t need international law,” he explained.

Trump’s “America First” policy―redolent of traditional great power imperialism―is complemented by other measures showing contempt for key international institutions. Trump quickly withdrew the U.S. government from leading UN agencies like the World Health Organization and the UN Human Rights Council, refused to participate in the UN Relief and Works Agency, and announced plans to withdraw from UNESCO. On January 7, 2026, the White House followed up by announcing U.S. withdrawal from 66 international and UN entities. It has also withheld at least two years of mandated dues to the UN’s regular budget and has placed sanctions on the judges and chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

Clearly, Trump has other priorities. He dramatically increased U.S. military spending soon after he returned to power and, in January 2026, proposed raising military spending by another $600 billion to a record $1.5 trillion, thereby creating his “Dream Military.” Apparently, this dream does not include ending the menace of nuclear annihilation, for―asked about renewing the last nuclear arms control agreement remaining with Russia, scheduled to expire next month―Trump responded: “If it expires, it expires.”

Unfortunately, leaders of other nations are also working full-time to destroy what remains of international law and humanity’s hopes for the future.

Vladimir Putin has stopped at nothing to revive what he considers Russia’s imperial glory by waging nearly four years of war to conquer and annex his far smaller, weaker neighbor, Ukraine. Ignoring strong condemnations by the UN General Assembly, the International Court of Justice, and the International Criminal Court, Putin has pressed on with an imperialist war that has reduced cities to rubble, damaged or destroyed thousands of schools and health care facilities, and sent 6 million Ukrainians fleeing abroad. The wounded or dead number hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians and as many as 1.2 million Russian soldiers.

Nor is this the extent of Putin’s military interventionism. Until quite recently, he conducted a brutal bombing campaign for nearly a decade in Syria to prop up the Assad dictatorship against its domestic foes. He also employed the Wagner Group, a shadowy private mercenary army headquartered in Russia, to conduct military operations elsewhere in the Middle East and in numerous African nations.

Like Trump, Putin has scrapped nuclear arms control agreements and occasionally threatened nuclear war.

Other national rulers, enamored with military power and widening their realms, have also turned their countries into rogue nations. Kim Jong Un, despite offers from the South Korean and U.S. governments to improve diplomatic relations, has chosen instead to dramatically expand North Korea’s nuclear arsenal, threaten nuclear war, and dispatch more than 14,000 combat troops to help Russia subdue Ukraine. Benjamin Netanyahu, while constantly claiming Israel’s victimization, has in fact superintended a genocidal slaughter of Palestinian civilians, staged military attacks on numerous nations, and―in defiance of a ruling by the International Court of Justice―refused to end Israel’s decades-long occupation of Palestinian territory.

And yet, the possibilities for reversing this sad state of affairs are enormous, for―thanks to a variety of factors, ranging from increases in knowledge to advances in economic productivity―it’s finally feasible for all of humanity to lead decent and fulfilling lives.

No longer is poverty necessary, for the enormous global economy can produce adequate food, goods, and services for all the world’s people.

Human health and longevity can be improved substantially, thanks to breakthroughs in science and medicine.

Education, communications, transportation, and culture have made huge strides toward enriching human existence and could finally be made available to all.

Meanwhile, the rise of the United Nations and of international law holds the promise of moving beyond the violent, bloodstained past and securing peace, human rights, and justice on the international level.

Although it’s tragic that powerful forces seem intent on building an unjust, lawless, and violent planet, let’s not forget that another world remains possible. Indeed, with an organized international effort, it could be a wonderful world.

by Donna Park | Dec 19, 2025 | Peace

Given my long-term interest in international affairs, I went to see the recently released movie, “Nuremberg,” to revisit the issue of how a court of law can be used to convict those guilty of war crimes. As a result, several parts of the film left me uneasy and looking for a better way to govern our world.

A statement in the film made by Hermann Goering, one of the most powerful leaders of Germany’s Nazi Party from 1933 to 1945, particularly struck me. He told the American psychologist whose job was to get to know him and keep him alive for the trial: “I am a prisoner because you won and we lost, not because you’re morally superior.” Goering suggested that if the Germans won the war, the Americans could have been brought to trial for dropping two nuclear bombs on Japan in August 1945.

Although, of course, Goering was a monster, his suggestion that the war’s victors were also responsible for war crimes has a disturbing element of truth to it. According to the K=1 Project, Center for Nuclear Studies at Columbia University, within the first few months after the bombing between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civilians, died in Hiroshima and Nagasaki due to the force and excruciating heat of the explosions as well as deaths caused by acute radiation exposure.

Indeed, the preparations for the Nuremberg war crimes trials were closely interwoven with the atomic bombings. The London Charter that created the International Military Tribunal for the prosecution of Nazi war criminals was signed on August 8, 1945―two days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and one day before the atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

It’s also worth pondering what would have happened to the war crimes trials of Nazi leaders if the four major Allied powers―the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union—had not all agreed to them. Would the trials have occurred at all?

In fact, the world lacked an institutional structure to hold an individual accountable for war crimes until the Rome Statute, an international treaty, was adopted at the Rome Conference on July 17, 1998. Effective beginning July 1, 2002, the Rome Statute created the International Criminal Court (ICC). According to its website, the ICC “investigates and, where warranted, tries individuals charged with the gravest crimes of concern to the international community: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and the crime of aggression. As a court of last resort, it seeks to complement, not replace, national Courts.”

Despite this breakthrough, the ICC is facing serious difficulties. Only 125 nations have ratified the Rome Statute, with the non-signers including China, Russia, Israel, India, Iran, and the United States. Furthermore, the U.S. government, under the presidency of Donald Trump, has recently imposed damaging economic sanctions against several members of the ICC. Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin has refused to surrender to the ICC for investigation of war crimes, while Benjamin Netanyahu has refused to submit to the court’s authority in connection with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Holding individuals accountable for the gravest crimes should be a high priority of our world. We should not accept a world in which individuals can commit genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression with impunity. But officials of major powers continue to obstruct the operations of the ICC and to act with impunity.

How can we move forward to creating a world in which international law and its obligations receive proper respect?

We can do so by looking back to San Francisco and the promises made there in 1945 during the creation of the United Nations (UN). As World War II was ending, representatives of 50 countries gathered in that city from April 25 to June 26 to draft and sign a Charter for the UN in the hopes of fostering international security and preventing another world war. There were many compromises made in the initial Charter, the biggest being the veto in the Security Council granted to the 5 permanent members. But this veto was balanced with a promise to revisit the Charter in no more than 10 years.

Accordingly, Article 109, paragraph three of the Charter promised a vote in the UN General Assembly by 1955 on whether to hold a conference for all member states to review the Charter. This decision only requires a majority vote of the 193 members of the General Assembly and any seven members of the 15-member states in the Security Council. There is no possibility of a veto in connection with this vote, so it can pass even if all five permanent members oppose the conference.

Unfortunately, no such vote has ever been taken at the General Assembly. We are now 70 years past the promised date. The multi-dimensional crises facing our world, including our inability to hold individuals accountable for the gravest crimes against humanity, demand such a vote, followed by the strengthening of the UN Charter and the international law it is supposed to enforce. Our world should be governed using the rule of law, not military might.

The recently formed Article 109 Coalition is now working towards a conference to review and strengthen the UN Charter. Concerned Americans should learn more about it and take action to support it. There is a better way to govern our world and to keep humanity safe and secure from military threats and crimes against humanity. Let’s move forward with it!

by Lawrence Wittner | Oct 14, 2025 | Peace

Although Albert Einstein is best-known as a theoretical physicist, he also spent much of his life grappling with the problem of war.

In 1914, shortly after he moved to Berlin to serve as director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Physics, Einstein was horrified by the onset of World War I. “Europe, in her insanity, has started something unbelievable,” he told a friend. “In such times one realizes to what a sad species of animal one belongs.” Writing to the French author Romain Rolland, he wondered whether “centuries of painstaking cultural effort” have “carried us no further than . . . the insanity of nationalism.”

As militarist propaganda swept through Germany, accompanied that fall by a heated patriotic “Manifesto” from 93 prominent German intellectuals, Einstein teamed up with the German pacifist Georg Friedrich Nicolai to draft an antiwar response, the “Manifesto to Europeans.” Condemning “this barbarous war” and the “hostile spirit” of its intellectual apologists, the Einstein-Nicolai statement maintained that “nationalist passions cannot excuse this attitude which is unworthy of what the world has heretofore called culture.”

In the context of the war’s growing destructiveness, Einstein also helped launch and promote a new German antiwar organization, the New Fatherland League, which called for a prompt peace without annexations and the formation of a world government to make future wars impossible. It engaged in petitioning the Reichstag, challenging proposals for territorial gain, and distributing statements by British pacifists. In response, the German government harassed the League and, in 1916, formally suppressed it.

After the World War came to an end, Einstein became one of the Weimar Republic’s most influential pacifists and internationalists. Despite venomous attacks by Germany’s rightwing nationalists, he grew increasingly outspoken. “I believe the world has had enough of war,” he told an American journalist. “Some sort of international agreement must be reached among nations.” Meanwhile, he promoted organized war resistance, denounced military conscription, and, in 1932, drew Sigmund Freud into a famous exchange of letters, later published as Why War.

Although technically a Zionist, Einstein had a rather relaxed view of that term, contending that it meant a respect for Jewish rights around the world. Appalled by Palestinian-Jewish violence in British-ruled Palestine, he pleaded for cooperation between the two constituencies. In 1938, he declared that he would “much rather see reasonable agreement with the Arabs on the basis of living together in peace than the creation of a Jewish state.” He disliked “the idea of a Jewish state with borders, an army, and a measure of temporal power,” plus “the development of a narrow nationalism within our own ranks.”

The most serious challenge to Einstein’s pacifism came with the Nazi takeover of Germany in 1933 and the advent of that nation’s imperialist juggernaut. “My views have not changed,” he told a French pacifist, “but the European situation has.” As long as “Germany persists in rearming and systematically indoctrinating its citizens in preparation for a war of revenge, the nations of Western Europe depend, unfortunately, on military defense.” In his heart, he said, he continued to “loathe violence and militarism as much as ever; but I cannot shut my eyes to realities.” Consequently, Einstein became a proponent of collective security against fascism.

Fleeing from Nazi Germany, Einstein took refuge in the United States, which became his new home. Thanks to his renown, he was approached in 1939 by one of his former physics students, Leo Szilard, a Hungarian refugee who brought ominous news about advances in nuclear fission research in Nazi Germany. At Szilard’s urging, Einstein sent a warning letter to President Franklin Roosevelt about German nuclear progress. In response, the U.S. government launched the Manhattan Project, a secret program to build an atomic bomb.

Einstein, like Szilard, considered the Manhattan Project necessary solely to prevent Nazi Germany’s employment of nuclear weapons to conquer the world. Therefore, when Germany’s war effort neared collapse and the U.S. bomb project neared completion, Einstein helped facilitate a mission by Szilard to Roosevelt with the goal of preventing the use of atomic bombs by the United States. He also fired off an impassioned appeal to the prominent Danish physicist, Niels Bohr, urging scientists to take the lead in heading off a dangerous postwar nuclear arms race.

Neither venture proved successful, and the U.S. government, under the direction of the new president, Harry Truman, launched the nuclear age with the atomic bombing of Japan. Einstein later remarked that his 1939 letter to Roosevelt had been the worst mistake of his life.

Convinced that humanity now faced the prospect of utter annihilation, Einstein resurrected one of his earlier ideas and organized a new campaign against war. “The only salvation for civilization and the human race,” he told an interviewer in September 1945, “lies in the creation of a world government, with security of nations founded upon law.” Again and again, he reiterated this message. In January 1946, he declared: “As long as there exist sovereign states, each with its own, independent armaments, the prevention of war becomes a virtual impossibility.” Consequently, humanity’s “desire for peace can be realized only by the creation of a world government.”

In 1946, he and other prominent scientists, fearful of the world’s future, established the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists. As chair of the new venture, Einstein repeatedly assailed militarism, nuclear weapons, and runaway nationalism. “We shall require a substantially new manner of thinking,” he said, “if mankind is to survive.”

Until his death in 1955, Einstein continued his quest for peace, criticizing the Cold War and the nuclear arms race and calling for strengthened global governance as the only “way out of the impasse.”

Today, as we face a violent, nuclear-armed world, Einstein’s warnings about unrestrained nationalism and his proposals to control it are increasingly relevant.

P.S.: Albert Einstein was a member of the National Advisory Council of the World Federalist Association, the predecessor of the Citizens for Global Solutions Education Fund.

by Jerry Tetalman | Oct 14, 2025 | Peace, UN Reform

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the major countries of the world have been aligning in two different blocs: NATO (which includes most European nations, the United States, and Canada), Japan, and South Korea, on one side, and Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, and India on the other. Both blocs of countries are supporting their side in the war with weapons, trade, or troops. The negotiations to end the Ukraine-Russia war have so far failed due to Vladimir Putin’s reluctance to engage. NATO has so far only supplied weapons and military support. Still, it has been careful not to confront Russia with troops directly―probably because Russia has a large nuclear arsenal and the United States and NATO are trying to avoid a full-scale war. This strategy, so far, has resulted in a protracted stalemate.

If allowed to spread and escalate, however, the Ukraine-Russia war might trigger World War III.

So, how does the United States deal with this dilemma? One option is to do more of what it has been doing: provide more weapons and sanctions, in the hope that they will bring Putin to the negotiating table in earnest. Another, more daring approach is to look at what causes war and then address the root cause of war.

We live in a world where most nations or groups of nations solve their disputes through military force rather than the force of law. But in some parts of the world, we have replaced war with law and government. For example, the European Union has created peace between its member states, such as France and Germany, countries that had fought bitterly against one another in World Wars I and II. Now these nations settle their disputes by voting in the European Parliament and the European Union courts.

Why has the European Union succeeded in creating peace among its members while the United Nations has failed in these efforts? The answer lies in the fact that the United Nations is based on treaty law, a voluntary system of agreements among nations that lacks an enforcement mechanism that true law uses.

A new, more powerful, and democratic United Nations, however, could create peace among the world’s countries. By convening a UN reform conference under Article 109 of the UN charter, it would be possible to engage the world’s nations in creating a rules-based system of international law that is enforceable rather than voluntary. Building a civilized world based on law and rules, rather than on military power, would create a global framework for peace, and hopefully, reverse the schism of the world into warring camps.

Would such a framework solve the Russia-Ukraine war? Not directly, but it would provide an institution capable of resolving it.

If left on their current trajectory, international relations and military conflict will soon reach a dark place that will be difficult to recover from. The alternative is not radical; indeed, rules and laws provide the basis of civilization, and today they are desperately needed at the international level. These can be provided by a structure of limited world government, similar to that of the European Union. Individual nations would remain free to develop their own laws dealing with their internal affairs, but, in international affairs, they would abide by the laws between countries. In this fashion, a small piece of sovereignty would be exchanged for a peaceful world.

The world’s nations can begin this process by invoking Article 109 of the UN Charter to call for a global conference to craft a new, more effective United Nations. For such a mission to succeed, many details must be worked out, but the alternative of more war and destruction is unacceptable.

by Lawrence Wittner | Mar 26, 2025 | Global Justice, Peace

Although the nations of the world have pledged to respect a system of international law and global responsibility, the recent behavior of several countries provides a sharp challenge to this arrangement.

For over three years, the Russian government has conducted a brutal military invasion, occupation, and annexation of Ukraine―the largest and most devastating military operation in Europe since World War II. Defying Russia’s international obligations―including a peace treaty it signed with Ukraine, a ruling by the International Court of Justice demanding Russia halt its military operations in Ukraine, the UN Charter, and repeated UN General Assembly condemnations of Russian behavior by an overwhelming majority of the world’s nations―the Putin regime has stubbornly persisted with Russia’s imperialist aggression against its smaller, weaker neighbor.

The consequences have been horrific. Russian and Ukrainian military forces are estimated to have suffered a total of roughly a million deaths or injuries. Moreover, the war has taken a severe toll on Ukraine’s civilian population, with some 42,000 civilians killed or injured and over 10 million more fleeing the country or internally displaced. In July 2024, it was estimated that, thanks to the Russian military’s indiscriminate bombing and shelling of civilian infrastructure, Russia had damaged more than 1,600 Ukrainian medical centers and destroyed over 200 hospitals. In the first year-and-a-half of the war, Human Rights Watch reported, the Russian invasion “devastated schools and kindergartens throughout the country,” with “over 3,790 educational facilities . . . damaged or destroyed.” A more recent study by this leading human rights organization noted that, in areas of Ukraine that Russian forces occupy, they have “committed war crimes and crimes against humanity. These include torture and killings of civilians, sexual violence, enforced disappearances, and forcible transfers and unlawful deportations of Ukrainians” to Russia.

For its part, the Israeli government has long been at odds with the United Nations over Israel’s mistreatment of Palestinians and, particularly, its refusal to end its military occupation of the Palestinian territory it conquered during the 1967 Mideast war. Committed to building a Greater Israel, rightwing Israeli government officials have seized Palestinian land in the occupied West Bank and flooded it with about 700,000 heavily-subsidized Israeli settlers. In turn, the UN General Assembly, by an overwhelming vote, has called upon Israel to comply with international law and withdraw its military forces, cease new settlement activity, and evacuate its settlers from the West Bank.

The simmering Israeli-Palestinian conflict erupted once again in October 2023, when, in response to an Hamas terrorist attack, Benyamin Netanyahu, Israel’s prime minister, launched a full-scale military invasion of Gaza with a colossal humanitarian impact. An estimated 46,788 Palestinians have been killed, most of them civilians, and 110,453 have been injured. According to the United Nations, 1.9 million people (90 percent of the population) have been internally displaced thanks to the Israeli bombing campaign, 69 percent of all structures have been destroyed (including 50 percent of hospitals, with the rest just partially functional), and about 1,060 medical workers have been killed. Thanks to the Israeli government’s blockade of food and water supplies, an estimated 91 percent of the population have faced severe levels of hunger.

Although only recently restored to the White House, Donald Trump has already embarked on an ambitious program of scrapping U.S. international commitments and proceeding, instead, with U.S. empire-building. Ordering U.S. sanctions on the International Criminal Court, as well as a U.S. pullout from two key UN agencies (the World Health Organization and the Human Rights Council), he has also chosen a U.S. ambassador to the UN, Representative Elise Stefanik, who has promised to bring the world organization into line with Trump’s “America First” priorities. Moreover, the American president has abruptly terminated nearly all USAID programs, putting millions of people around the world at risk of starvation, disease, and death. In sharp contrast to the severe cuts in domestic social spending that Trump is implementing, he has called for increased military spending, potentially raising the annual U.S. military expenditure from $842 billion to over $1 trillion. This enhanced military power should prove useful, for since returning to office he has championed seizing the Panama Canal and Greenland, taking over Gaza, and annexing Canada as the 51st American state.

In all three cases, the reckless pursuit of narrowly-defined national interests has taken precedence over the shared interests of the world community.

Nor is this an accident, for Putin, Netanyahu, and Trump are caught up in overheated nationalist dreams quite out of touch with global reality. Today, as human survival is threatened by climate catastrophe, a renewed nuclear arms race, disease pandemics, and widespread poverty―crises that cry out for global solutions―these government officials and their rightwing counterparts in other lands are driven by nationalist fantasies. Putin is enamored with Russian imperial glory, Netanyahu is obsessed with visions of Greater Israel, and Trump is intoxicated with America First. And, in their respective fantasies, each of them takes on heroic stature as the Supreme Leader.

Unfortunately, we have seen this phenomenon, along with its catastrophic consequences, many times before.

Fortunately, however, multitudes of people realize that things need not be this way. Indeed, Putin, Netanyahu, and Trump are out of line with the views of many national leaders and social movements that have recognized, and continue to recognize, that the reckless pursuit of narrow national interests is a recipe for disaster. To avoid this disaster, our far-sighted predecessors created the United Nations, the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court, and other international institutions. That is also why these institutions must be strengthened, for without the enforcement of world law, national irresponsibility will thrive.

Indeed, if humanity is to survive in coming decades, it is imperative that reckless competition and conflict among nations give way to cooperation and collective action. War must be replaced by peace, privilege by equality, and the rule of force with the force of law.

Above all, no nation can go it alone, for we are all part of one world and must act accordingly.

by Matt McDonough | Oct 17, 2024 | Peace

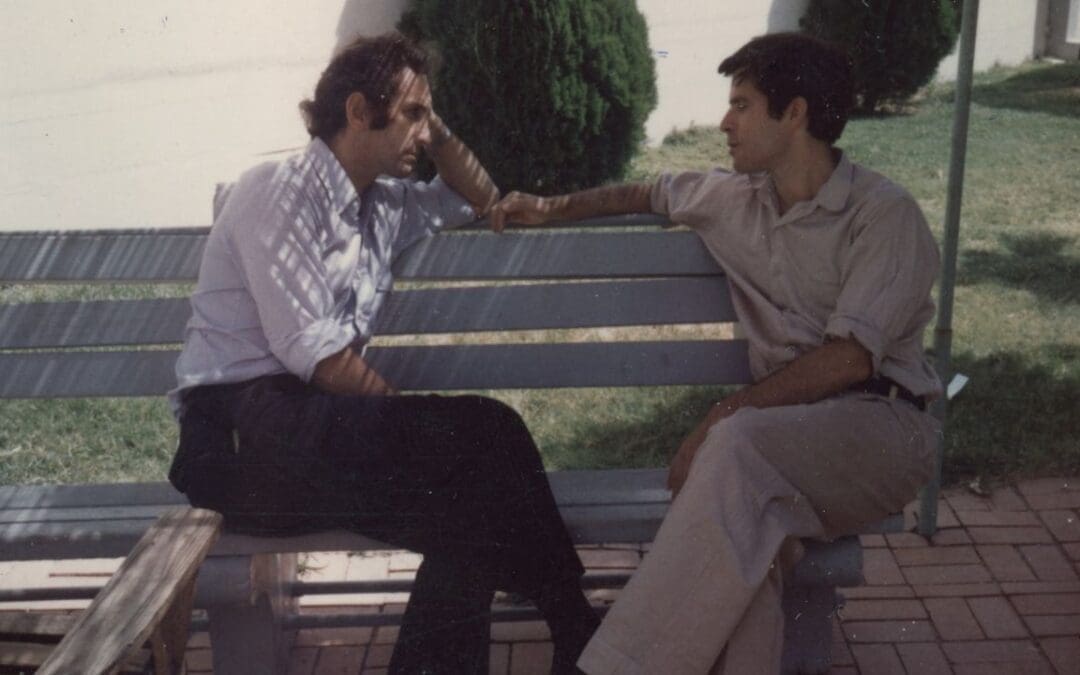

This summer, Citizens for Global Solutions lost a valuable member of our National Advisory Council, Randy Kehler, who, at age 80, passed in July.

Randy was a peace activist, dedicated to the eradication of war and to the expansion of justice at both the local and global level. In 1969 Randy refused to go to war. He returned his draft card, thereby committing a felony and blocked entrance to an induction center. For these actions Randy served nearly two years in federal prison.

I first met Randy when my ex-wife became his administrative assistant. Over the ensuing years I got to see his passion and commitment up close. I don’t know if I have ever met a harder worker.

Randy was known as the father of the Freeze Campaign, a national effort to get the two superpowers to agree to freeze their nuclear arsenals at the then current levels. Observers claim that these efforts influenced the Reagan administration to push for arms reduction talks with the Soviet Union.

Randy is perhaps best known as the person who influenced Daniel Ellsberg to release the Pentagon Papers. The release of that document led directly to a substantial increase in resistance to the Vietnam war. On a number of occasions Mr. Ellsberg said, “No Randy Kehler, no Pentagon Papers.”

Randy was a lifelong tax resistor. He felt that he could not support the U.S. military. He calculated the tax that he owed and contributed that amount to charity. In 1989, this resulted in the Internal Revenue Service seizing his house in Colrain, MA. When he refused a judge’s order to vacate, he once again found himself in jail. He eventually lost his home and he and his wife, Betsy Corner, moved into a house owned by her parents.

Over a cup of coffee, I once mentioned how unjust I thought it was that he was jailed for resisting the draft. He immediately corrected me. His conscience told him that he had to resist the draft, but he broke the law, and the government did what it had to do. He felt no resentment. This was a typical example of Randy’s integrity.

Randy will be greatly missed.

Image Source: Daniel Ellsberg and Randy Kehler seated at a bench, ca. 1971. Daniel Ellsberg Papers (MS 1093). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.