by Lawrence Wittner | Mar 2, 2024 | Disarmament

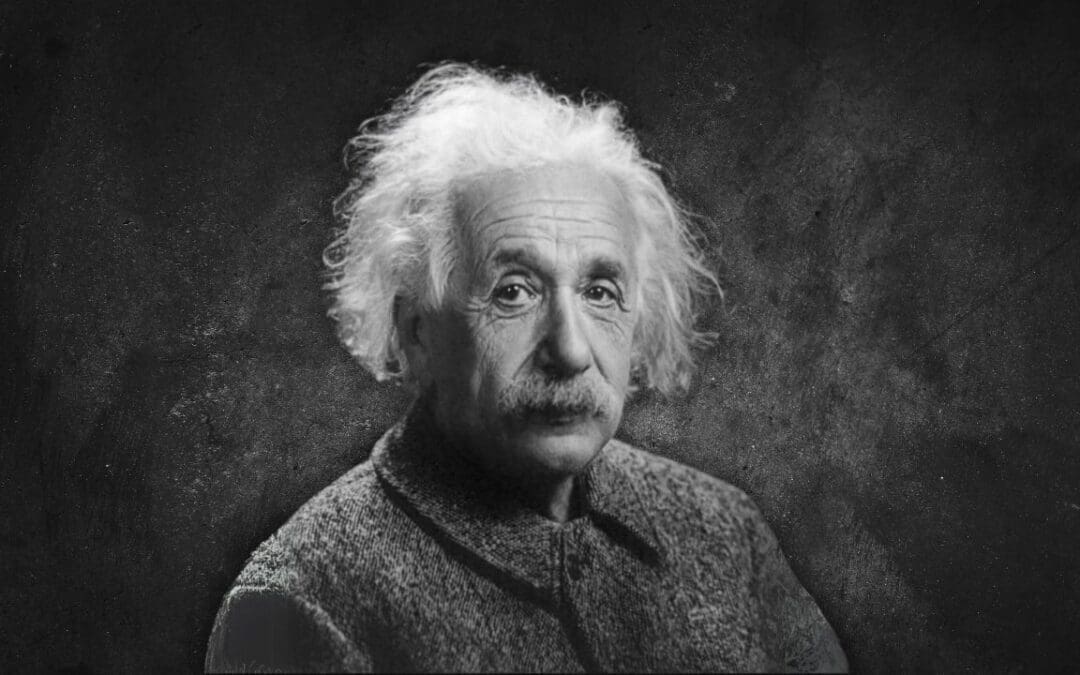

Although the popular new Netflix film, Einstein and the Bomb, purports to tell the story of the great physicist’s relationship to nuclear weapons, it ignores his vital role in rallying the world against nuclear catastrophe.

Aghast at the use of nuclear weapons in August 1945 to obliterate the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Einstein threw himself into efforts to prevent worldwide nuclear annihilation. In September, responding to a letter from Robert Hutchins, Chancellor of the University of Chicago, about nuclear weapons, Einstein contended that, “as long as nations demand unrestricted sovereignty, we shall undoubtedly be faced with still bigger wars, fought with bigger and technologically more advanced weapons.” Thus, “the most important task of intellectuals is to make this clear to the general public and to emphasize over and over again the need to establish a well-organized world government.” Four days later, he made the same point to an interviewer, insisting that “the only salvation for civilization and the human race lies in the creation of a world government, with security of nations founded upon law.”

Determined to prevent nuclear war, Einstein repeatedly hammered away at the need to replace international anarchy with a federation of nations operating under international law. In October 1945, together with other prominent Americans (among them Senator J. William Fulbright, Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, and novelist Thomas Mann), Einstein called for a “Federal Constitution of the World.” That November, he returned to this theme in an interview published in the Atlantic Monthly. “The release of atomic energy has not created a new problem,” he said. “It has merely made more urgent the necessity of solving an existing one. . . . As long as there are sovereign nations possessing great power, war is inevitable.” And war, sooner or later, would become nuclear war.

After the creation, in early 1947, of United World Federalists, the U.S. branch of the growing world federalist movement, Einstein served on its Advisory Board.

Einstein also promoted world federalist ideas through a burgeoning atomic scientists’ movement in which he played a central role. To bring the full significance of the atomic bomb to the public, the newly-formed Federation of American Scientists put together an inexpensive paperback, One World or None, with individual essays by prominent Americans. In his contribution to the book, Einstein wrote that he was “convinced there is only one way out” and this necessitated creating “a supranational organization” to “make it impossible for any country to wage war.” This hard-hitting book, which first appeared in early 1946, sold more than 100,000 copies.

Given Einstein’s fame and his well-publicized efforts to avert a nuclear holocaust, in May 1946 he became chair of the newly-formed Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, a fundraising and policymaking arm for the atomic scientists’ movement. In the Committee’s first fund appeal, Einstein warned that “the unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking, and thus we drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.”

Even so, despite the fact that Einstein, like most members of the early atomic scientists’ movement, saw world government as the best recipe for survival in the nuclear age, there seemed good reason to consider shorter-range objectives. After all, the Cold War was emerging and nations were beginning to formulate nuclear policies. An early Atomic Scientists of Chicago statement, prepared by Eugene Rabinowitch, editor of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, underscored practical considerations. “Since world government is unlikely to be achieved within the short time available before the atomic armaments race will lead to an acute danger of armed conflict,” it noted, “the establishment of international controls must be considered as a problem of immediate urgency.” Consequently, the movement increasingly worked in support of specific nuclear arms control and disarmament measures.

In the context of the heightening Cold War, however, taking even limited steps forward proved impossible. The Russian government sharply rejected the Baruch Plan for international control of atomic energy and, instead, developed its own atomic arsenal. In turn, U.S. President Harry Truman, in February 1950, announced his decision to develop a hydrogen bomb―a weapon a thousand times as powerful as its predecessor. Naturally, the atomic scientists were deeply disturbed by this lurch toward disaster. Appearing on television, Einstein called once more for the creation of a “supra-national” government as the only “way out of the impasse.” Until then, he declared, “annihilation beckons.”

Despite the dashing of his hopes for postwar action to end the nuclear menace, Einstein lent his support over the following years to peace, nuclear disarmament, and world government projects.

The most important of these ventures occurred in 1955, when Bertrand Russell, like Einstein, a proponent of world federation, conceived the idea of issuing a public statement by a small group of the world’s most eminent scientists about the existential peril nuclear weapons brought to modern war. Asked by Russell for his support, Einstein was delighted to sign the statement and did so in one of his last actions before his death that April. In July, Russell presented the statement to a large meeting in London, packed with representatives of the mass communications media. In the shadow of the Bomb, it read, “we have to learn to think in a new way. . . . Shall we . . . choose death because we cannot forget our quarrels? We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest.”

This Russell-Einstein Manifesto, as it became known, helped trigger a remarkable worldwide uprising against nuclear weapons in the late 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in the world’s first significant nuclear arms control measures. Furthermore, in later years, it inspired legions of activists and world leaders. Among them was the Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev, whose “new thinking,” modeled on the Manifesto, brought a dramatic end to the Cold War and fostered substantial nuclear disarmament.

The Manifesto thus provided an appropriate conclusion to Einstein’s unremitting campaign to save the world from nuclear destruction.

Image courtesy of US Govt. Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

by Lawrence Wittner | Feb 20, 2024 | Climate Justice, Disarmament

For some time, it’s been apparent that the world’s nations are not meeting the growing challenges to human survival.

A key challenge comes from modern war.

Over the centuries, as military weapons have grown ever more destructive, war-related devastation has grown accordingly. World War II was the deadliest military conflict in human history, with an estimated 70-85 million people perishing from the war directly or through war-caused disease, famine, and other indirect factors. Most of the dead were civilians. In addition, many millions of people were wounded―blinded, crippled, driven mad, or otherwise ravaged by the vast carnage. Large portions of the globe had become a charnel house, with the battered survivors left to desperately scavenge for food amid the burnt-out rubble and ruin.

Although some scholars have pointed out that warfare has declined since then, and especially since the end of the Cold War, there was a sharp turnabout in 2022, when the wars in Ethiopia and Ukraine contributed to more battle-related deaths than in any year since 1994. By late 2023, Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine alone had produced an estimated 315,000 killed or injured Russian troops, while the number of casualties among Ukrainian troops and civilians, though unknown, is certainly enormous. Among these and the many other wars currently raging―in Sudan, Myanmar, Ethiopia, the Sahel, and Syria, to name only a few―the recent one in Gaza, with the fastest daily death rate of the 21st century, is particularly alarming, having already led to nearly 30,000 deaths and nearly 70,000 injuries.

And then, of course, there’s nuclear war, which emerged in 1945 with the utter annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and which now has the capacity to end virtually all life on earth. Amid public threats from leaders of nuclear-armed nations to launch a nuclear war, the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists have set their “Doomsday Clock” at its closest ever to apocalypse.

War―particularly nuclear war―is probably the fastest way to extinguish the human race, but there are other crises underway that, on a longer-range basis, seem likely to accomplish the same task.

The most serious of these crises is environmental. In recent decades, there has been a rapid loss of biodiversity, with the sixth mass extinction of wildlife clearly accelerating. Pollution has grown dramatically. This includes pollution of land and water caused by chemicals and by plastic (which takes 400 years to decompose) and of the air caused by industrial, motor vehicle, and other emissions (leading to an estimated 4.2 to 7 million human deaths annually). Damage to the soil, caused especially by use of toxic chemicals and other pollutants, as well as by deforestation, has become particularly severe. The United Nations has estimated that some 40 percent of the planet’s soil is now degraded.

A key element in the environmental collapse is the growing climate catastrophe, caused primarily by the burning of fossil fuels. Melting icecaps and rising sea levels, unprecedented hurricanes, floods, and wildfires, and ocean acidification are all well underway. Together with unsustainable farming practices, rising temperatures have produced growing food and water scarcity. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres declared that, unless immediate action is taken, there will be a “global food emergency that could have long term impacts on hundreds of millions of adults and children.” Furthermore, it is estimated that, by 2025, two-thirds of the world’s people might face water shortages. Commenting on the deteriorating climate situation, Guterres declared gloomily in September 2023 that “humanity has opened the gates to hell.”

The rise of rightwing nationalism provides yet another challenge to human survival. In recent years, rightwing political movements―headed by authoritarian demagogues such as Donald Trump (United States), Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil), Vladimir Putin (Russia), Narendra Modi (India), Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Turkey), Marine Le Pen (France), Benjamin Netanyahu (Israel), Viktor Orban (Hungary), and their counterparts in other lands―have transformed the landscape of world politics. Appealing to xenophobia, militarism, racism, and religious prejudice, they have made great strides toward stirring up longstanding hatreds in their ruthless quest for power. A key to their success along these lines has been their call to revive the ostensible glory of their own nations by purging their internal enemies and triumphing over other, ostensibly inferior, countries abroad. Redolent of the fascist movements of the 1930s, this Radical Right approach portends worldwide turmoil, violence, and destruction.

Of course, it might not be too late to head off these developments. After all, in the twentieth century, humanity did manage to defeat the drive of the rightwing maniacs who established fascist regimes and launched vast wars to rule the world. In the aftermath of the chaos and destruction of World War II, humanity did manage to create the United Nations and to extend the range of international law. And, still later, as the planet stood on the brink of nuclear war, humanity did manage to roll back the nuclear menace and, for a time, halt the nuclear arms race and curb the prevalence of war.

Moreover, there are a great many efforts underway―by social movements and some far-sighted governments―to address the contemporary crises. Peace, environmental, and political action movements have flourished and brought forth demands for sweeping changes in public policy. In addition, some social movements, recognizing the global nature of the problems facing humanity, have called for enhanced global governance to cope with the severe threats posed by war, environmental devastation, and violations of human rights. The Summit of the Future on the horizon in September 2024 has been hailed as a “once in a generation” opportunity for meaningful reform of the global governance architecture. This watershed moment could be seized as a chance to correct course and avert disaster for humanity and the planet.

Even so, as the world once again veers toward destruction, it’s clear that it’s getting late―very late―to avert catastrophe.

Image Source: Doomsday Clock சஞ்சீவி சிவகுமார், CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Sovaida Maani Ewing | Feb 8, 2024 | Peace

Like it or not, our world has become so interconnected and interdependent that events that have hitherto been regarded as regional in nature now threaten our well-being everywhere. The Ukraine war triggered global food and energy crises, global inflation, exacerbated the worldwide refugee crisis, and renewed the specter of a nuclear war. The war in Gaza has added to these woes by sparking reactions that threaten global shipping through the Suez Canal, putting a further dent in our global economy by raising consumer prices. We must act swiftly and effectively now to stem the cancerous spread of violence before we find ourselves engulfed in a global conflagration.

The international community must step up and shoulder a responsibility it has, for too long, abdicated: to maintain and restore peace in the world. We can begin by going beyond mere words and adopting mechanisms to operationalize and implement a principle known as the Responsibility to Protect, adopted unanimously by 193 nations at the UN Summit of world leaders in 2005. It provides that if a government is unable or unwilling to protect its people, it falls to the international community to step in and shoulder that responsibility.

A mechanism that is worth considering along these lines is that of making Gaza an international trust for a limited period of time until it is ready for self-governance. Even if there is no appetite to revive the Trusteeship Council, an organ of the United Nations which was suspended (though not dismantled) in 1994, we can revive and apply its attributes to create this trust as a stepping-stone for peace in the Middle East. We should urge the UN General Assembly to create an ad hoc Trusteeship Council that would act as a time-limited cocoon (say of 5 years) around Gaza, allowing it to heal at all levels until it is able to take up its role as a mature member of the international community of nations. The case of South West Africa’s evolution to becoming Namibia provides us with a useful precedent for setting up such an ad hoc Council and warns us of pitfalls to avoid.

Many benefits flow from this approach: first, Gaza would be under the direct administration and control of the UN, which would appoint an ad hoc Trusteeship Council for Gaza (and possibly parts of the West Bank) composed of a mix of countries from the region (such as Jordan, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia) and beyond (like Canada, Germany, France, the UK and Australia) on condition that they are committed to the well-being of all parties to the conflict and to establishing peace in the region. Having such a Council frees Israel from the burden of administering these territories and affords the Palestinians the space to recover, develop and grow into an independent self-governing entity.

Second, Gaza could be demilitarized, thereby ensuring the security of both its people and its neighbors. Here again, we can turn to the successful experiences of Northern Ireland and East Timor for lessons in how best to achieve this.

Third, an economic recovery and reconstruction plan akin to the Marshall Plan could be developed for Gaza. Moreover, the administering authority should be able to monitor all funds coming into Gaza and ensure that they will be used solely for constructive and peaceful purposes and not diverted for the purchase of weapons or instruments of war that can threaten the peace.

Fourth, a system of education that is rooted in teaching coexistence and peace and is coupled with the provision of training in good governance should be introduced, allowing for a cadre of potential leaders representative of the people of Gaza to emerge.

Last, the UN can arrange for free and fair elections to be held, as it did in Namibia.

It is time to take bold steps to spare our world from the ravages of war and establish a lasting peace.

This article was originally published in PeaceVoice.

Image Credits: Stepping stones across the R.Mole below Box Hill by Jonathan Hutchins, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Lawrence Wittner | Jan 31, 2024 | Peace

Although, according to the UN Charter, the United Nations was established to “maintain international peace and security,” it has often fallen short of this goal. Russia’s ongoing military invasion of Ukraine and the more recent Israeli-Palestinian war in Gaza provide the latest examples of the world organization’s frequent paralysis in the face of violent international conflict.

The hobbling of the Security Council, the UN agency tasked with enforcing international peace and security, bears the lion’s share of the responsibility for this weakness. Under the rules set forth by the UN Charter, each permanent member of the Security Council has the power to veto Security Council resolutions. And these members have used the veto, thereby blocking UN action.

This built-in weakness was inherited from the UN’s predecessor, the League of Nations. In that body, a unanimous vote by all member nations was required for League action. Such unanimity of course, proved nearly impossible to attain, and this fact largely explains the League’s failure and eventual collapse.

The creators of the United Nations, aware of this problem when drafting the new organization’s Charter in 1944-45, limited the number of nations that could veto Security Council resolutions to the five major military powers of the era―the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France.

Other nations went along with this arrangement because these “great powers” insisted that, without this acceptance of their primacy, they would not support the establishment of the new world organization. The Charter’s only restriction on their use of the veto was a provision that it could not be cast by a party to a dispute―a provision largely ignored after 1952. Fortifying the privileged position of these five permanent Security Council members, the Charter also provided that any change in their status required their approval.

In this fashion, the great powers of the era locked in the ability of any one of them to block a UN Security Council resolution that it opposed.

Not surprisingly, they availed themselves of this privilege. By May 2022, Russia (which took the seat previously held by the Soviet Union), had cast its veto in the Security Council on 121 occasions. The United States cast 82 vetoes, Britain 29, China 17, and France 16.

As the Council’s paralysis became apparent, proponents of UN action gravitated toward the UN General Assembly. This UN entity expanded substantially after 1945 as newly-independent countries joined the United Nations. Moreover, no veto blocked passage of its resolutions. Therefore, the General Assembly could serve not only as a voice for the world’s nations, but as an alternative source of power.

The first sign of a shift in power from the Security Council to the General Assembly emerged with the General Assembly’s approval of Resolution 377A: “Uniting for Peace.” The catalyst was the Soviet Union’s use of its veto to block the Security Council from authorizing continued military action to end the Korean War. Uniting for Peace, adopted on November 3, 1950 by an overwhelming vote in the General Assembly, stated that, “if the Security Council, because of lack of unanimity of the permanent members, fails to exercise its primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security . . . the General Assembly shall consider the matter immediately with a view to making appropriate recommendations to members for collective measures.” To facilitate rapid action, the resolution created the mechanism of the emergency special session.

Between 1951 and 2022, the United Nations drew upon the Uniting for Peace resolution on thirteen occasions, with eleven cases taking the form of the emergency special session. In addition to dealing with the Korean War, Uniting for Peace resolutions addressed the Suez confrontation, as well as crises in Hungary, Congo, Afghanistan, Palestine, Namibia, and Ukraine. Although, under the umbrella of Uniting for Peace, the General Assembly could have recommended “armed force when necessary” against violators of international peace and security,the Assembly adopted that approach only during the Korean War. On the other occasions, it limited itself to calls for peaceful resolution of international conflict and the imposition of sanctions against aggressors.

These developments had mixed results. In 1956, during the Suez crisis, shortly after the General Assembly held a Uniting for Peace session calling for British and French withdrawal from the canal zone, both countries complied. By contrast, in 1980, when a Uniting for Peace session called for an end to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Moscow ignored the UN demand. It could do so thanks to the fact that General Assembly resolutions are mere recommendations and, as such, are not legally binding.

Even so, global crises in recent years have heightened pressure to provide the United Nations with the ability to take effective action. In April 2022, shortly after the Russian government vetoed a Security Council resolution calling for Russia’s unconditional withdrawal from Ukraine, the General Assembly voted that, henceforth a Security Council veto would automatically trigger a meeting of the Assembly within ten days of the action to cope with the situation.

Meanwhile, numerous nations have been working to restrict the veto in specific situations. In July 2015, the UN Accountability, Coherence, and Transparency Group proposed a Code of Conduct against “genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes” that called upon all Security Council members to avoid voting to reject any credible draft resolution intended to prevent or halt mass atrocities. By 2022, the Code had been signed by 121 member nations. France and Mexico have taken the lead in proposing the renunciation of the veto in these situations.

These reform initiatives are likely to be addressed at the September 2024 UN Summit of the Future.

Clearly, as the history of the United Nations demonstrates, if the world organization is to maintain international peace and security, it must be freed from its current constraints.

This article was originally published in PeaceVoice.

by Jerry Tetalman | Jan 19, 2024 | Peace

The war in Ukraine has destabilized and polarized the international order. It pits two nuclear-armed superpowers, the United States and Russia, against each other. Any miscalculation can take all of us to nuclear Armageddon. This war has created untold human misery. Ending this war should be a top priority for humankind. How can the war be ended and on what terms?

Conventional wisdom holds that wars end in one of two ways. Either one side wins and the other loses or they negotiate a peace agreement by coming to an understanding that both sides can live with. The Russian invasion of Ukraine currently looks like a stalemate, with little territory being won or lost in the last year and both sides seemingly adhering to a position requiring total victory.

Russia seems to be playing the long game, of waiting out the resolve of the West to fund and support Ukraine. Sanctions on Russia have had an effect, but it still sells oil to China, India, and much of the world.

Ukraine’s goal is to regain its lost territory, maintain its current territory, and achieve security against future invasions. Russia wants to control all of Ukraine and wants to prevent it from joining NATO. The question is, can a peace agreement be made that both sides can live with?

Countries at war start to look for alternatives when victory is no longer assured or even likely. This war has reached that point. Negotiations give countries options in a no-win situation. Are the parties ready to negotiate?

Peace agreements are reached by making a win-win deal where both sides get something they want out of it. Of course, they need to compromise and give up some things as well.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is a key to any peace deal, for he must be willing to negotiate and implement any agreement reached. But the other key is Ukraine, whose territory has been invaded, occupied, and annexed by Russia.

The “deciders” will be Russia (essentially Putin) and Ukraine (the Zelensky administration). They will be the ones with representatives at the negotiating table.

Beyond “the table,” there are other influencers, such as those who support Ukraine with arms and funding–the European Union and the US. Some tacitly support Russia by continuing commerce with Putin and by not voting in the UN to sanction Russia.

If an understanding and peace settlement is to be reached between Ukraine and Russia, we must consider what institution is most capable of facilitating the necessary negotiations. The United Nations which is the world’s largest and most important international peace organization is the logical party, for this task, according to its charter, its goal is to “prevent the scourge of war.” Unfortunately, the UN Security Council is hobbled by the fact that Russia and the other great powers that emerged victorious in World War II―the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and China―exercise veto power. And Russia has vetoed Security Council action in connection with the Ukraine war.

Another option is for UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to organize serious peace negotiations. The role of the Secretary-General is that of chief diplomat for all nations. That official is charged with mediation and appointment of envoys to broker peace agreements. In getting such negotiations off the ground, he might find it useful to draw upon countries such as China or Turkey, both of which have a rapport with Putin.

The International Court of Justice was foreseen by the UN Charter as the primary method of resolution of disputes between Countries, offering law as an alternative to war. The law needs enforcement, and the ICJ is limited in this area. Its preliminary ruling against Russia, nearly two years ago, was ignored by Putin. The International Court of Justice has resolved the majority of the cases they hear through a voluntary agreement. If we are to move from an international system based on war and military force to a system based on law and justice, we need to empower and expand the International Court of Justice to include all nations in the UN.

We must also move forward with reform of the UN Security Council, thereby ending its paralysis when it comes to enforcing world peace and security. A more democratic United Nations, with greater funding and enforcement power, is necessary if we hope to survive this dangerous time. We can move from war to law by reforming and strengthening the United Nations, but it will take some creative thinking and action by all of us.

This article was originally published in Black Star News.

Image Credits: UN Photo/Manuel Elías

by Daniel Perell | Dec 30, 2023 | Climate Justice

My father was always the smartest person in the room. Despite never studying medicine, he once assisted a pre-med friend in preparing for an exam entirely by recalling intricate anatomical structures from a biology course he had taken thirty years prior.

My father was also a smoker. Some of my earliest memories are my tearful pleas to him to stop, knowing, as we both did, the risks. My dad did the math and determined that he didn’t yet need to change behavior. He would coin clever phrases like “maybe I might” and “I want to want to quit.” This reticence instilled in me, from a very young age, a curiosity about what truly motivates people to change. Is it data? We had that. Is it the cries of children? We had that, too.

As I awoke earlier this week to the news that agreement had been reached in Dubai, I, like many, chose to see hope in this small step. I will work tirelessly to contribute my small portion to this great collective effort to stave off the worst consequences of climate change. Yet a question remains in my mind—to what degree can these agreements bend the curve of our behavior? How can we ensure the trajectory will be meaningfully different with this consensus having been reached?

I look to examples the international community has created to shape the behavior of governments and humanity more broadly. The Security Council, the human rights system, the sustainable development goals. Each has had an impact in its own way. A stronger enforcement mechanism like the Security Council increases legitimacy, but limits consensus. A systematic and mandatory review system, like the Universal Periodic Review, ensures oversight and greater fact-finding, but is dependent on Member State compliance for results. And an entirely voluntary system, like the Sustainable Development Goals, can inspire the masses and allow the tracking of progress. Yet for the SDGs, and based on recent reports, the curve has yet to be bent sufficiently to achieve the prosperity a bright-eyed 2015 international community hoped for.

These are all helpful in their own right. But the forces of inertia are strong. Volition and motivation are needed.

Nowhere is this more relevant than in the case of climate agreements. Many nations which have contributed the least to climate change must respond to consequences not of their making. And those which exercise an outsized influence on the shape and direction of human affairs, for reasons of history and current priorities, are being asked to sacrifice a degree of short-term well-being of their economies for the long-term security of themselves and others. The science is clear; the issue is summoning the will to overcome the uncomfortable to achieve the necessary. In a way, these countries are my brilliant father.

When my dad was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer—the risk of which was increased by his smoking habit—he quit immediately. It was remarkable. But it was too late. He might have gotten cancer anyway, and it isn’t fair to place blame not knowing the alternate reality. But he certainly did not follow the rules of the precautionary principle in his behavior.

I am heartened to know that in communities around the world, action is being taken now to improve humanity’s relationship with the natural world. People are not waiting. Agreements like those reached in Dubai, in Paris, and elsewhere are important. They represent the consensus of governments, and we, as well-wishers of humanity and the planet, should encourage and expect ever higher ambition.

Yet regardless of our opinion of the outcome in 2023, we have a responsibility to continue looking for the stores of motivation and the diversity of options for individuals, institutions, and communities to make the necessary changes in light of the mounting evidence. If any lesson is to be taken from my family, it is that waiting is not a viable option.

This article was originally published in Bahá’í International Community’s blog.

Photo credit: Baha’i International Community