by Lawrence Wittner | Dec 9, 2024 | Global Justice, Human Rights

The International Criminal Court’s recent issuance of arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant for crimes against humanity and war crimes in Gaza has stirred up a considerable backlash. Dismissing the charges as “absurd and false,” Netanyahu announced that Israel would “not recognize the validity” of the ICC’s action. U.S. President Joe Biden denounced the arrest warrants as “outrageous,” while the French government reversed its stance after agreeing to support them.

Thanks to a vigorous campaign by human rights organizations, the International Criminal Court (ICC) became operational in 2002, with the mandate to prosecute individuals for genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and, after 2018, the crime of aggression. Nations ratifying the Rome Statute, the ICC’s authorizing document, assumed responsibility for arresting these individuals and submitting them to the Court for trial. The ICC prosecutes cases only when countries are unwilling or unable to do so, for it was designed to complement, rather than replace, national criminal justice systems.

Operating with clearly delimited powers and limited funding, the ICC, headquartered at the Hague, has thus far usually taken modest but effective action to investigate, prosecute, and convict perpetrators of heinous atrocity crimes.

Although 124 nations have ratified the Rome Statute, Russia, China, the United States, India, Israel, and North Korea are not among them. Indeed, the world’s major military powers, accustomed to the privileged role in world affairs that their armed might usually afford them, have often been at odds with the ICC, for it has the potential to investigate, prosecute, and convict their government officials.

The desire of the “great powers” to safeguard themselves from the enforcement of international law is exemplified by the record of the U.S. government. Although President Bill Clinton signed the Rome Statute in December 2000, he warned about “significant flaws in the treaty,” among them the inability to “protect US officials.” Refusing to support U.S. Senate ratification, he recommended that his successor continue this policy “until our fundamental concerns are satisfied.”

U.S. President George W. Bush “unsigned” the treaty in 2002, pressured other nations into bilateral agreements requiring them to refuse to surrender U.S. nationals to the Court, and signed the American Servicemembers Protection Act, authorizing the use of military force to liberate any Americans held for crimes by the ICC.

Although, subsequently, the Bush and Obama administrations warmed somewhat toward the Court, then engaged in prosecuting African warlords and Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, President Donald Trump reverted to staunch opposition in 2018, informing the UN General Assembly that the U.S. government would not support the ICC, which he claimed had “no jurisdiction, no legitimacy, and no authority.” In 2020, the Trump administration imposed economic sanctions and visa restrictions on top ICC officials for any effort to investigate the actions of U.S. personnel in Afghanistan.

Like the United States, Russia initially signed the Rome treaty. It withdrew its signature, however, after Ukraine appealed to the ICC in 2014 and 2015 to investigate war crimes and crimes against humanity that Russia committed in Ukraine. The ICC did launch a preliminary investigation that, after the full-scale Russian military invasion of February 2022 and the Russian murder of Ukrainian civilians and prisoners of war in Bucha, expanded into a formal investigation. Taking bold action in March 2023, the ICC issued arrest warrants for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova for the mass kidnapping of Ukrainian children.

Having previously denied wrongdoing in Bucha, the Russian government reacted furiously to the kidnapping charge. “The very question itself is outrageous,” declared Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov, and the ICC’s decisions “are insignificant for the Russian Federation.” Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chair of the Russian Security Council and a former Russian president, publicly threatened a Russian hypersonic missile attack upon the ICC headquarters, remarking: “Judges of the court, look carefully at the sky.” Subsequently, Moscow issued arrest warrants for top ICC officials.

Meanwhile, the United States has continued its ambivalence toward the ICC. President Joe Biden scrapped the Trump sanctions against the Court and authorized the sharing of information and funding for it in its investigations of Russian atrocities in Ukraine. But he reaffirmed “our government’s longstanding objection to the Court’s efforts to assert jurisdiction” over U.S. and Israeli officials.

The incoming Trump administration seems likely to take a much harsher line. The Republican-led House of Representatives recently passed legislation to sanction the ICC, while Republican Senator Lindsay Graham, calling the Court a “dangerous joke,” urged Congress to sanction its prosecutor, and warned U.S. allies that, “if you try to help the ICC, we’re going to sanction you.”

Given the policies of the “great powers,” are the Court’s efforts to enforce international law futile?

Leading advocates of human rights don’t think so. “This is a big day for the many victims of crimes committed by Russian forces in Ukraine,” declared Amnesty International upon learning of the Court’s arrest warrants for top Russian officials. “The ICC has made Putin a wanted man and taken its first step to end the impunity that has emboldened perpetrators in Russia’s war.” Similarly, Kenneth Roth, the former executive director of Human Rights Watch, stated that the ICC’s issuance of arrest warrants for top Israeli officials represented “an important step toward justice for the Palestinian people. . . . Israeli generals must now think twice about proceeding with the bombing and starving of Palestinian children.”

And, indeed, the ICC’s actions have started to bear fruit. Invited to South Africa to participate in a BRICS conference, Putin canceled his visit after his hosts explained that, in light of the arrest warrant, he was no longer welcome. Also, later that year, Russian officials returned hundreds of Ukrainian children to their parents. Although the results of the ICC’s action against Israeli officials are only starting to unfold, numerous countries have promised to honor the arrest warrants for Netanyahu and Gallant.

Even so, the ICC’s enforcement of international criminal justice would be considerably more effective if the major powers stopped obstructing its efforts.

by Lawrence Wittner | Nov 22, 2024 | Global Cooperation

The latest rollout of the hyper-nationalist “America First” policy underscores the world’s long-term slide toward catastrophe.

Within nations, when conflicts inevitably erupt, there are laws, as well as police, courts, and governments that enforce the laws.

On the global level, however, governance is quite limited. The UN Security Council, responsible under the UN Charter for maintaining international peace and security, is frequently hamstrung by the veto, which the five great powers of 1945 insisted upon according to themselves. By this April, it had been employed 321 times. Although the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court deliver legally binding judgments, based on international law, such judgments are not always obeyed. The UN General Assembly votes on key international issues as well, but such votes are merely advisory. Consequently, these international organizations issue laudable statements, while the most powerful nations all too frequently defy them and go on their merry, marauding way.

The Russian government is currently continuing its massive military invasion of Ukraine and annexing its territory while ignoring the demands of the UN General Assembly and the International Court of Justice to end Russia’s aggression and withdraw from Ukraine. Similarly, the Israeli government ignores the demands of these world organizations to end its brutal war upon and occupation of Palestine.

From the overwhelming votes in the UN General Assembly to condemn the Russian and Israeli invasions, we can see what most of the world’s nations want done to address these terrible situations. But there is no implementation of their demand to respect international law―law that lacks effective international enforcement.

Over the course of human history, this international lawlessness has contributed to a might-makes-right approach to world affairs, in which militarily powerful nations play the dominant role. Naturally, then, nations have gravitated toward military buildups, making some very powerful, indeed.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, the top military spenders in 2023 (the latest year for which figures are available) are the United States ($916 billion), China ($296 billion), Russia ($109 billion), and India ($84 billion). But others―Israel ($28 billion) and North Korea (amount unknown)―also rank among the big-time military spenders. All told, the nations of the world devoted at least $2,443 billion to war and preparations for war, an increase over the previous year of nearly 7 percent.

Military spending is not the only way to measure militarism. The Global Peace Index 2024, compiled by the Institute for Economics and Peace, used the level of societal safety and security, the extent of ongoing domestic and international conflict, and the degree of militarization to examine 163 independent nations and territories. Not surprisingly, the major military powers ranked low on the scale of peacefulness, including China (88th), India (116th), the United States (132nd), North Korea (152nd), Israel (155th), and Russia (157th).

By contrast to these military behemoths―possessing the mightiest military forces in world history, including arsenals of nuclear weapons―the United Nations has remained a relatively anemic organization, speaking truth but lacking power.

Sometimes, the major military powers cope with the explosive global situation by making deals with one another―although such deals rarely create the basis for a peaceful world. For example, the August 23, 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (better known as the Nazi-Soviet Pact) provided for détente between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, two highly-militarized nations that had previously been at odds. In this secret protocol, Hitler and Stalin agreed to share Poland and give Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, and other East European territories to the Soviet Union. On September 1, Germany invaded western Poland, thereby beginning World War II. Soon thereafter, the Soviet Union took action to seize its share of the spoils. As early as July 1940, however, the German High Command began planning its invasion of the Soviet Union, which occurred the following June, ending this cozy arrangement.

On other occasions, major military powers have formed alliances. Wary of a military attack by their rivals or eager to bolster their strength for a military attack upon them, these “great powers” have enhanced their military might by creating military alliances with weaker nations. The weaker nations, for their part, sometimes seek alliances with the militarily powerful to guarantee their own security.

But alliances, too, have provided a shaky basis for maintaining international peace. During the Cold War, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (dominated by the United States) and the Warsaw Pact (dominated by the Soviet Union) engaged in remarkably dangerous nuclear confrontations. Furthermore, both alliances experienced serious internal convulsions. In 1956, Hungary withdrew from the Warsaw Pact, leading to a Soviet invasion that slaughtered 2,500 Hungarians and sent 200,000 fleeing abroad.

Today, the traditional system of every-nation-for-itself is leading to disaster. There are currently 56 active military conflicts in the world, the largest number since the end of World War II. These conflicts are also becoming more internationalized, with 92 nations engaged in a conflict beyond their borders. According to the Global Peace Index, “there has been a significant rise in both conflicts and battle deaths in the past two decades, with battle deaths reaching a thirty-year high.”

Overarching this grim toll lies a revived nuclear arms race, increasingly likely to erupt into a nuclear war that will annihilate most life on Earth.

In this situation, there is a desperate need for effective global governance. Or, to put things differently, the world needs a stronger United Nations―strong enough to resolve conflicts among nations and, thereby, maintain international peace and security.

The task of strengthening global governance is difficult, but not impossible. There are ways to limit the use of the veto in the UN Security Council (as championed by many nations), transfer security issues to the UN General Assembly (where there is majority rule and no veto), and increase the jurisdiction of international judicial bodies. It’s also necessary and possible to provide the UN with an independent source of income to fund an expanded range of activities.

The time has come to transform the United Nations into a federation of nations that can effectively uphold international law―a government for the world. With such a government, we would have a much better chance of restraining outlaw nations and averting the nuclear catastrophe that looms before us.

by Matt McDonough | Oct 17, 2024 | Peace

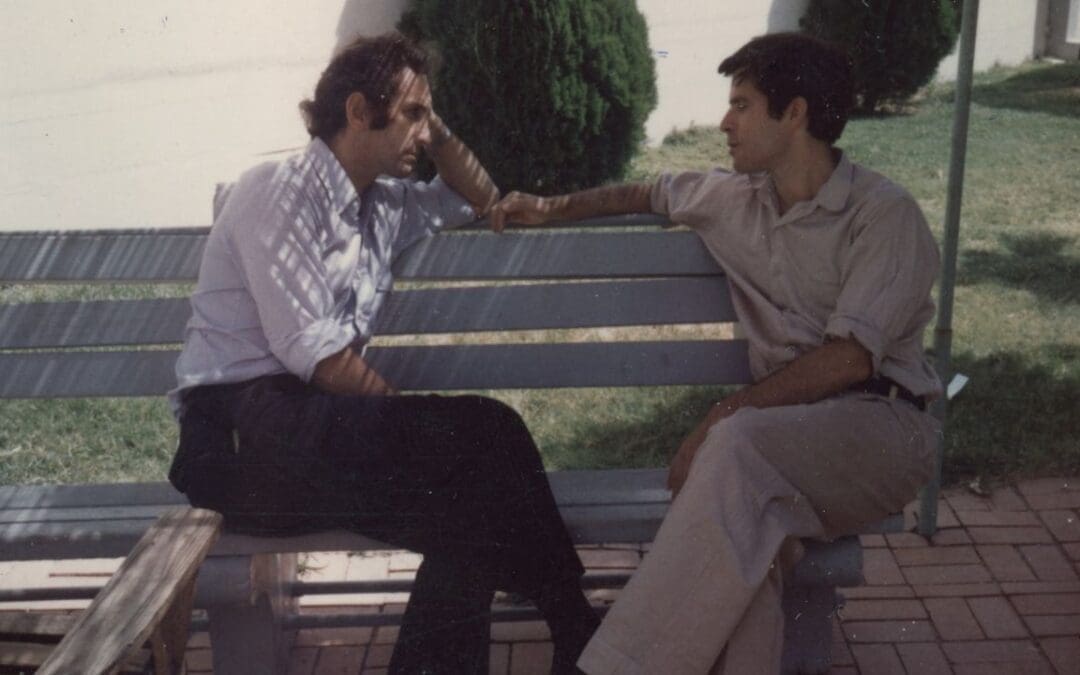

This summer, Citizens for Global Solutions lost a valuable member of our National Advisory Council, Randy Kehler, who, at age 80, passed in July.

Randy was a peace activist, dedicated to the eradication of war and to the expansion of justice at both the local and global level. In 1969 Randy refused to go to war. He returned his draft card, thereby committing a felony and blocked entrance to an induction center. For these actions Randy served nearly two years in federal prison.

I first met Randy when my ex-wife became his administrative assistant. Over the ensuing years I got to see his passion and commitment up close. I don’t know if I have ever met a harder worker.

Randy was known as the father of the Freeze Campaign, a national effort to get the two superpowers to agree to freeze their nuclear arsenals at the then current levels. Observers claim that these efforts influenced the Reagan administration to push for arms reduction talks with the Soviet Union.

Randy is perhaps best known as the person who influenced Daniel Ellsberg to release the Pentagon Papers. The release of that document led directly to a substantial increase in resistance to the Vietnam war. On a number of occasions Mr. Ellsberg said, “No Randy Kehler, no Pentagon Papers.”

Randy was a lifelong tax resistor. He felt that he could not support the U.S. military. He calculated the tax that he owed and contributed that amount to charity. In 1989, this resulted in the Internal Revenue Service seizing his house in Colrain, MA. When he refused a judge’s order to vacate, he once again found himself in jail. He eventually lost his home and he and his wife, Betsy Corner, moved into a house owned by her parents.

Over a cup of coffee, I once mentioned how unjust I thought it was that he was jailed for resisting the draft. He immediately corrected me. His conscience told him that he had to resist the draft, but he broke the law, and the government did what it had to do. He felt no resentment. This was a typical example of Randy’s integrity.

Randy will be greatly missed.

Image Source: Daniel Ellsberg and Randy Kehler seated at a bench, ca. 1971. Daniel Ellsberg Papers (MS 1093). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

by Lawrence Wittner | Sep 18, 2024 | Global Justice

Are the nations of the world doomed to go on fighting the brutal, horrifying wars that have long characterized human history?

We might well wonder about that as we watch, aghast, while Israeli armed forces slaughter thousands of Palestinian civilians, Russian military might relentlessly pounds Ukrainian towns and cities into rubble, and new, bloody wars erupt in numerous other lands.

Why does such widespread destruction and human suffering persist in the modern, ostensibly “civilized,” world?

A variety of explanations have been advanced. Some observers point to capitalism, others blame dictatorial rule, while still others place the onus on xenophobia, religious differences, racism, and toxic masculinity.

Each of these factors has some weight. Certainly greed, authoritarian arrogance, inflamed nationalism, religious and racial animosities, and male violence have played some role in dividing people and, thereby, fostering wars among them over the course of history.

But are these factors sufficient to explain the stubborn persistence of war? After all, wars existed long before the advent of capitalism and, furthermore, since then, non-capitalist (for example, Communist) nations have repeatedly waged wars, even against one another. Similarly, democratic nations have plunged regularly into numerous wars, some against their fellow democracies. Moreover, even countries whose populations have friendly ties, have the same racial composition and religion, and have taken major strides toward gender equality (including admission of women to the armed forces and top posts in government) seem quite willing to prepare for and engage in war with each other.

Something is clearly missing from these explanations of widespread international violence―something fundamental. Could it be the structure of international relations?

International relations specialists have long argued that the driving force behind international war is global anarchy. Humanity, like war, has existed for thousands of years. But, although humans have gradually created governments to establish effective laws regulating behavior within their territories―regions, cities, states, and, ultimately, nations―they have failed to do so for the world. Thus, on the global level, nations have been left largely to their own devices. The resulting situation resembles the American Wild West, characterized by the absence of law enforcement and the prevalence of heavily armed gangs.

For centuries, scholars have pointed to the need for creating transnational structures to end this global nightmare. The theologian and diplomat Hugo Grotius helped develop the concept of international law, while writers such as Dante Alighieri, Immanuel Kant, and H.G. Wells promoted the idea of global governance.

After the atomic bombing of Japan and the ensuing scramble for nuclear weapons starkly revealed the peril of nuclear annihilation, the call for a full-scale transformation of international relations became even sharper. Albert Einstein, the chair of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, stated bluntly: “Mankind’s desire for peace can be realized only by the creation of a world government.”

Norman Cousins, editor of one of America’s major magazines of the era (the Saturday Review), played a key role in channeling Einstein’s call into a postwar campaign for a global federation of nations. “The only security for Americans today, or for any people,” Cousins contended, is “a system of world order that enables nations to retain sovereignty over their own cultures and institutions but that creates a workable authority for regulating the behavior of nations in their relationships with one another.” Cousins served as president of United World Federalists (which morphed into the World Federalist Association and, eventually, Citizens for Global Solutions), the U.S. member organization of the World Federalist Movement.

Benjamin Ferencz, the U.S. prosecutor at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials of the late 1940s, became an important popularizer of this world federalist approach. In his widely-read book, PlanetHood, Ferencz told Americans that, in the United States, “we have four layers of government: city, county, state, and national,” created “to avoid anarchy within our nation.” Thus, adding “one more layer of government will enable us to have an abundant future on this planet.” Indeed, “international governance―something like a United Nations of the World―will rescue us from our deadly predicament.”

Critics, of course, might argue that a United Nations already exists, and has often proved unable to prevent the recurrence of war. But Ferencz’s answer―and, usually, the answer of the world federalist movement―was that, although the United Nations had significant accomplishments to its credit, the UN Charter “was deliberately made weak” by the major powers. As a result, it “did not give the United Nations the binding strength needed to get rid of international lawlessness.” Ultimately, “the only way to permanently solve the problem of war is to replace the Law of Force with the Force of Law.” This perspective led, in recent years, to the establishment of the LAW not War campaign, designed to promote the universality of the International Court of Justice.

World federalists can also point to a dramatic decline in war when independent nations accepted limitations on their sovereignty. In the late eighteenth century, as 13 British North American colonies gained their independence, they could have followed the usual global pattern of war with one another. But, instead, they gradually created a federal union (the United States) and fought only one war within their ranks during the following 235 years. Similarly, although European nations had undergone centuries of war with each other before they went at it again in World War II, members of the European Union, formed in the aftermath of that devastating war (and now encompassing 27 nations), succeeded in ending war among them.

The issue of transcending the ages-old practice of international war certainly remains relevant today. Indeed, the United Nations is moving forward with plans for a Summit of the Future in late September. Designed to address “global governance,” among other issues, the Summit provides yet another opportunity for nations to empower the world organization to maintain international peace through the enforcement of world law.

Is that goal realistic? Perhaps so, perhaps not. But how realistic is it to continue the anarchy of nations, which today threatens universal death and destruction?

Image source: https://www.asymmetricalhaircuts.com/episodes/in-memoriam-benjamin-b-ferencz/

by Sovaida Maani Ewing | Aug 30, 2024 | Peace

The intensifying cascade of global crises including intractable wars, massive human rights atrocities, nuclear proliferation, climate change and environmental degradation, the growing inequality between the rich and the poor, recurring bouts of global financial instability, and the increasing risks of pandemics to name but a few, call to mind the warning sounded by Arnold Toynbee, one of the most highly-regarded authorities and foremost experts on international affairs and world history in the 20th century, that humanity would be faced with an existential crisis followed by his recommendation as to what we, the family of nations, should do in response.

Toynbee contended that in the atomic age, humanity would have to choose between political unification and mass suicide. He believed the chief obstacle to political unification was a long-standing destructive habit of the West which he referred to as the habit of “divisive feeling” to which we tended to easily succumb as opposed to reaching for our more recently-adopted habit of “world-mindedness.” The good news he said was that just as new habits could be adopted, old ones could also be modified or abandoned. He stressed that as a general rule, we humans would opt to abandon even our most deeply-rooted habits once it became clear that clinging to them would spell disaster.

He recommended that we replace our outworn habit of divisive feeling with a new habit of common action on a worldwide scale through the creation of some form of limited world-state that would be empowered to act in humanity’s collective interest in certain narrow fields of endeavor. Already, as far back as the 1970’s he believed that the global community needed to engage in common action on a world-wide scale in at least two areas: to control atomic energy through a World Authority and to administer the production and distribution of food through another World Authority. Now, just over fifty years hence, we can confidently add climate change to this list.

Toynbee predicted that global circumstances we unwittingly created through our technological advancements would eventually force us to submit to a limited world government once we realized it was our only hope for salvation in the face of an existential threat. He believed we would wait until the eleventh hour before making a radical shift to establish such a government even though we would do this kicking and screaming all the way.

He was very clear in recognizing our visceral fears about and knee-jerk reaction in opposition to a world government that might become a draconian centralized bureaucracy imposing its will on local governments around the world. He made the following compelling arguments to dispel these fears.

Firstly, a world government should be minimal and should be limited in its sphere of action. World leaders should therefore confine the authority of a world government they established only to that which was strictly necessary for their self-preservation right now.

Secondly, he stressed that in the atomic age, world government should come about voluntarily through the mutual consent and cooperation of world powers rather than through the use of force. He warned that any attempt to impose political unity by force would be ineffective as it would only lead to stiff resistance and a resurgent nationalism as soon as an opportunity to revolt presented itself.

Thirdly, the prerequisite for such an endeavor to succeed lies in the universal adoption of an ideology of world-mindedness that we had never achieved before.

Toynbee believed that the structure of a limited world state would likely be a federal one in which previously independent units would voluntarily come together in a global union. He argued that this was the most likely scenario given that states generally prefer to preserve their identity and retain their autonomy to act locally; they would likely be willing to cede power to a world government only in limited areas in which it served their collective interests to do so.

Lastly, he believed that humanity needed to forge some unity of thought as to what constituted right and wrong. In other words, it was necessary to adopt a shared set of moral values that would serve to harmonize the disparate social and cultural heritages that had evolved independently of each other over the course of human history. Without fundamental agreement on moral issues he argued, it would be difficult to achieve political unification.

Given the rapid disintegration of countries and societies around the world and the accelerating fragmentation and polarization that are rending apart the fabric of our global society, is it not time for us to step up and make the choice to collaborate, cooperate and deepen our integration as a global society? To this end is it not time we take a step in the direction of collective maturity by voluntarily consenting to political unification by forming a limited democratic federal world government? Imagine what we could achieve if we engaged in collective and consultative decision-making in order to meet the pressing needs and the greatest global challenges of our time as opposed to opting for what Toynbee coined the “Great Refusal” that would inevitably result in carnage and devastation on a scale never before seen.

Image source: rawpixel.com

by Lawrence Wittner | Aug 8, 2024 | Peace

Although the current U.S. presidential campaign has focused almost entirely on domestic issues, Americans live on a planet engulfed in horrific wars, an escalating arms race, and repeated threats of nuclear annihilation. Amid this dangerous reality, shouldn’t we give some thought to how to build a more peaceful future?

Back in 1945, toward the end of the most devastating war in history, the world’s badly battered nations, many of them in smoldering ruins, agreed to create the United Nations, with a mandate to “maintain international peace and security.”

It was not only a relevant idea, but one that seemed to have a lot of potential. The new UN General Assembly would provide membership and a voice for the world’s far-flung nations, while the new UN Security Council would assume the responsibility for enforcing peace. Furthermore, the venerable International Court of Justice (better known as the World Court) would issue judgments on disputes among nations. And the International Criminal Court―envisioned at the time but created nearly four decades later―would try individuals for crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes of aggression. It almost seemed as if a chaotic, ungovernable, and bloodthirsty pack of feuding nations had finally evolved into the long-standing dream of “One World.”

But, as things turned out, the celebration was premature.

The good news is that, in some ways, the new arrangement for global governance actually worked. UN action did, at times, prevent or end wars, reduce international conflict, and provide a forum for discussion and action by the world community. Thanks to UN decolonization policies, nearly all colonized peoples emerged from imperial subjugation to form new nations, assisted by international aid for economic and social development. A Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, set vastly-improved human rights standards for people around the world. UN entities swung into action to address new global challenges in connection with public health, poverty, and climate change.

Even so, despite the benefits produced by the United Nations, this pioneering international organization sometimes fell short of expectations, particularly when it came to securing peace. Tragically, much international conflict persisted, bringing with it costly arms races, devastating wars, and massive destruction. To some degree, this persistent conflict reflected ancient hatreds that people proved unable to overcome and that unscrupulous demagogues worked successfully to inflame.

But there were also structural reasons for ongoing international conflict. In a world without effective enforcement of international law, large, powerful nations could continue to lord it over smaller, weaker nations. Thus, the rulers of these large, powerful nations (plus a portion of their citizenry) were often reluctant to surrender this privileged status.

Symptomatically, the five victorious great powers of 1945 (the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, France, and China) insisted that their participation in the United Nations hinged upon their receiving permanent seats in the new UN Security Council, including a veto enabling them to block Security Council actions not to their liking. Over the ensuing decades, they used the veto hundreds of times to stymie UN efforts to maintain international peace and security.

Similarly, the nine nuclear nations (including these five great powers) refused to sign the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which has been endorsed by the overwhelming majority of the world’s nations. Behind their resistance to creating a nuclear weapons-free world lies a belief that there is much to lose by giving up the status and power that nuclear weapons afford them.

Of course, from the standpoint of building a peaceful world, this is a very short-sighted position, and the reckless behavior and nuclear arrogance of the powerful have led, at times, to massive opposition by peace and nuclear disarmament movements, as well as by many smaller, more peacefully-inclined nations.

Thanks to this resistance and to a widespread desire for peace, possibilities do exist for overcoming UN paralysis on numerous matters of international security. Unfortunately, it would be very difficult to abolish the Security Council veto outright, given the fact that, under the UN Charter, the five permanent members have the power to veto that action, as well. But Article 27(3) of the Charter does provide that nations party to a dispute before the Council must abstain from voting on that issue―a provision that provides a means to circumvent the veto. In addition, 124 UN nations have endorsed a proposal to scrap the veto in connection with genocide, crimes against humanity, and mass atrocities, while the UN General Assembly has previously used “Uniting for Peace” resolutions to act on peace and security issues when the Security Council has evaded its responsibility to do so.

Global governance could also be improved through other measures. They include increasing the number of nations accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and securing wider ratification of the founding statute of the International Criminal Court (which has yet to be ratified by Russia, the United States, China, India, and other self-appointed guardians of the world’s future).

It won’t be easy, of course, to replace the law of force with the force of law. Only this May, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court took a bold step toward strengthening international norms by announcing that he was seeking arrest warrants for top Israeli officials and Hamas commanders for crimes in and around Gaza. In response, the Republican-controlled U.S. House of Representatives passed the “Illegitimate Court Counteraction Act,” legislation requiring the U.S. executive to impose sanctions on individuals connected with the ICC.

Despite the nationalist backlash, however, the time has arrived to consider bolstering international institutions that can build a more peaceful world. And the current U.S. presidential campaign provides an appropriate place for raising this issue. After all, Americans, like the people of other lands, have a personal stake in ensuring human survival.