Mondial Article (Winter 2025)

The Sword of Damocles Falls: The Impact of US Sanctions on the International Criminal Court (ICC)

Rebecca A. Shoot

Rebecca A. Shoot is the Editor-in-Chief of Mondial and Executive Director of Citizens for Global Solutions. She also serves in a pro bono capacity as Co-Convener of the Washington Working Group for the ICC and the ImPACT Coalition on International Judicial Institutions. She previously directed the Rome Statute Campaign of Parliamentarians for Global Action and held senior leadership positions with the American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative and the National Democratic Institute. She is admitted to practice law in the District of Columbia and speaks frequently on international justice issues. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

On February 6, 2025, as this issue of Mondial was about to go to publication, a proverbial sword of Damocles fell, as the administration of President Donald J. Trump imposed sanctions on the International Criminal Court (ICC), with an individual designation against its Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan shortly following. The long-anticipated maneuver came after months of speculation on whether—and advocacy against—sanctions would be imposed through legislation. While Congressional attempts to pass sanctions legislation ultimately failed, the Trump administration ultimately did so through Executive Order (EO). Primary sanctions target ICC staff and their families, with more individual designations expected to follow. Secondary sanctions target those who assist or provide support to designated persons. The penalty for violating the EO is up to 20 years in prison and/or a fine of US$1 million.

Asset freezes and entry restrictions are tools intended to combat individuals and entities that threat US national security. By applying these measures to a court that 125 countries—and on two occasions, the United Nations (UN) Security Council—have entrusted with providing accountability for atrocity crimes, the US has brought upon itself the stigma of siding with impunity over justice.

It is axiomatic that perpetrators of atrocities should want to undermine the ICC. In response to indictments of himself and senior officials, Russian President Vladimir Putin issued arrest warrants against the Prosecutor and Pre-Trial Chamber judges “merely for having faithfully and diligently carried out their judicial mandate per the statutory framework and international law,” in the words of ICC President Judge Tomoko Akane. What is unfathomable is when governments that purport to be grounded on principles of justice and the rule of law imperil the Court’s existence. This is currently the “extraordinary situation” in which the ICC finds itself; according to President Akane, “being threatened with draconian economic sanctions from three institutions of [a] permanent member of the Security Council as if it was a terrorist organisation. These measures would rapidly undermine the Court’s operations in all situations and cases and jeopardise its very existence.”

The US and the ICC: A Brief Primer

Volumes have been dedicated to the US’s relationship with the ICC. Without attempting a comprehensive exploration of the subject, a brief recapitulation is useful to contextualize recent developments.

Notwithstanding the at-times vociferous American opposition to the ICC, the US has not been monotonal in its policy toward the Court. The US relationship to the ICC is complex and, while often marked by tension, the US has profoundly contributed to the ICC when deemed in its interest. The American Bar Association (ABA) sent an observer to the post-WWII Nuremberg Trials, where a legal team led by Justice Robert H. Jackson worked with allies to prosecute Nazi leadership for crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

The ABA also participated actively as an Observer at the Rome Conference, as did many US nongovernmental organizations that comprise the Coalition for the ICC (CICC). The Rome Statute bears a strong imprint of US jurisprudence, attesting to the deep involvement in its drafting and negotiation by American diplomats and legal experts, including the first US Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes (now styled Global Criminal Justice), David Scheffer, who signed the treaty on behalf of President Clinton in the final hours it was open for signature at the United Nations headquarters.

The US influenced many aspects of the ICC’s design, including the incorporation of the principle of complementarity, which gives precedence to domestic courts over the ICC. While the American Service-Members’ Protection Act (ASPA) sought to protect US nationals from the ICC’s reach, recent years have seen expansion of the “Dodd Amendment,” enabling US cooperation with the Court in certain instances—notably with regard to the situation in Ukraine.

The US has directly or indirectly contributed to the arrest and surrender of suspects when doing so aligned with its foreign policy objectives, particularly in Africa. Broad cooperation with the UN and other partners enabled the arrest and transfer of the first two individuals surrendered to the ICC. More blatantly, in 2013, fugitive Congolese warlord Bosco Ntaganda walked into the US Embassy in Kigali and asked to be transferred to the ICC. Lord’s Resistance Army commander Dominic Ongwen followed suit two years later, surrendering to US forces in the Central African Republic. The US government expanded its Rewards for Justice Program in 2013 to include individuals indicted by the ICC, offering financial incentives for information leading to the capture of ICC fugitives, including Joseph Kony and other warlords.

The US also strongly supported the two situations referred to the ICC by the UN Security Council—Darfur and Libya—and has called for others to be committed to the Court’s justice, including the Syrian Arab Republic. The US joined 65 states to co-sponsor a resolution led by France to refer the ongoing alleged atrocities to the ICC, acting upon the recommendation of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, among others. It was ultimately vetoed by the Russian Federation and People’s Republic of China.

Perhaps less visibly the US has made voluntary contributions to the Trust Fund for Victims, an independent institution with a dual mandate to dispense reparations and provide assistance to victims, survivors, and communities affected by the atrocity crimes in the Court’s jurisdiction. Except on occasions during the Trump administration, the US has utilized its Observer Status to participate in the Assembly of States Parties (ASP), the ICC’s management oversight and legislative body (the US delegation attended but did not take the floor for a public statement at the 23rd ASP in December 2024). US nationals count among the approximately 1000 staff members from 109 different countries serving in all of the Court’s three organs, including as judicial clerks (such as the author did through the ICC’s Visiting Professional Programme). And US government and private sector actors have provided expertise and capacity building in the face of cybersecurity threats, including a major attack on the Court linked to Russian malfeasance.

The Road to Sanctions Against the ICC

The United States’ sanctions policy is a critical tool in its foreign policy arsenal, used to influence the behavior of foreign governments, entities, and individuals. Sanctions are basically intended to isolate an individual from their property as a punitive measure; they can target a variety of activities, including human rights violations, terrorism, cyberattacks, nuclear proliferation, and corruption. Well-known examples include “Magnitsky sanctions,” which target the worst abusers of human rights. Typically implemented by the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, they can include asset freezes, trade restrictions, financial transaction bans, and travel prohibitions. These measures aim to exert economic and diplomatic pressure without resorting to military intervention, and are often designed to be dynamic, with mechanisms to lift or tighten restrictions depending on the target’s behavior, thereby incentivizing compliance with US or international demands.

After months of fulmination by then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in retaliation primarily for pursuing investigations in Afghanistan that could potentially implicate US nationals, the US announced the imposition of sanctions and travel restrictions on the Chief Prosecutor and a senior member of her team under the previous Trump administration. At that time, human rights organizations, legal experts (including the President of the ABA), policy makers, and former diplomats from both US political parties cautioned that it was “uniquely dangerous, extreme, and unprecedented to utilize a mechanism designed to penalize criminals, their aiders, and abettors, against an independent judicial institution.” A task force commissioned by the American Society of International Law, led by the current and a former US Ambassador for Global Criminal Justice, Beth Van Schaack and Todd Buchwald, concluded that sanctions had “backfired” and Amb. Buchwald subsequently explained why “even a strong US reaction [to the ICC arrest warrants for Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant] should not include sanctions.”

With the precedent established, in 2024, following the Court’s announcement of potential arrest warrants for Israeli officials for alleged crimes committed in the context of the armed conflict between Israel and Hamas, the House of Representatives passed the so-called “Illegitimate Court Counteraction Act.” Although the bill’s full scope was ambiguous, the legislative intent was to punish foreign persons who aid, materially assist, or provide financial support for efforts by the ICC to undertake certain investigations and prosecutions. The bill’s passage was the culmination of Congressional anti-ICC efforts after previous abortive legislative attempts and rhetorical grandstanding, including a bipartisan open letter to the President led by the nominee for the next Secretary of State, in which he and co-authors from both parties called upon Biden to use “any means necessary” to thwart prosecution of US or allied personnel for war crimes.

The Biden administration strongly opposed the bill while also criticizing the ICC’s engagement in the Palestine situation. The previous Senate did not vote on the legislation, amid contentious negotiations between Democratic leaders and Republican supporters in the Foreign Relations Committee, which contributed to obstruction of that body’s work for months.

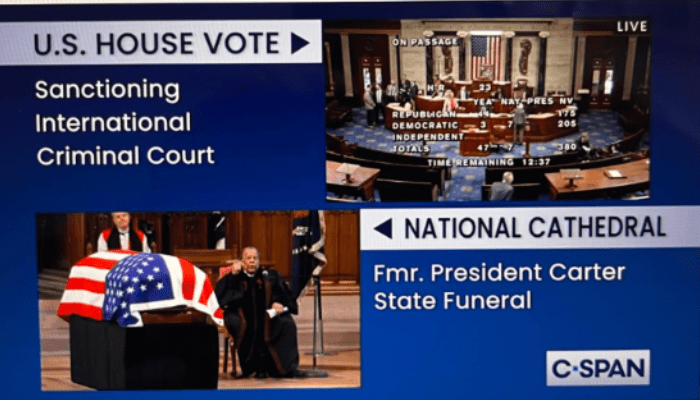

At the outset of the 118th Congress, Republican leadership announced the intent to take up the legislation once again. Despite vociferous opposition, including statements by the American Branch of the International Law Association’s Humanitarian Law Committee and the powerful New York City Bar Association, HR 23, passed the House of Representatives 243 to 140 (with one present vote). In an ironic twist, the floor debate coincided with the official state funeral of human rights champion President Jimmy Carter.

The juxtaposition of the House vote on ICC sanctions and President Carter’s funeral was stark for many observers. Photo courtesy of Elizabeth Evenson.

A flurry of advocacy coalesced as the bill reached the Senate. The Washington Working Group for the ICC coordinated an open letter signed by more than 130 civil society groups, faith-based organizations, and legal associations and held a press conference featuring a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and eminences from situation countries attesting to the impact of the ICC for victims and survivors. A group of European Member States penned a leaked démarche, urging against a “yay” vote. Even Microsoft, a partner of the Court, stepped up to lobby Democratic Senators.

Thanks in part to these efforts, the legislation failed to pass the necessary next hurdle in the Senate, with all but one Democrat voting against proceeding with the measure in a vote of 54-44 (Sen. John Fetterman, D-PA, was the lone exception with Sen. Jon Ossoff, D-GA, abstaining).

This was to be a short-lived and Pyrrhic victory. Not only would the Trump administration promulgate the EO just over a week after the failed Senate vote, but some Senate Democrats have indicated their willingness to accept a deal that would preserve much of the sanctions bill, with carve outs for US tech companies working with the ICC (but notably, not human rights defenders or victims advocates). Per Politico, Senior US Senator Lindsey Graham is “optimistic the Senate could still pass a bill that would sanction the International Criminal Court … [Senate Majority Leader John] Thune has also signaled that the sanctions bill isn’t totally dead.”

The Potentially Deleterious—and Perhaps Devastating—Impact of the New Sanctions on the ICC

The earlier imposition of sanctions targeting the ICC was narrow—denoting two officials—and short-lived. Enacted just four months before Biden was sworn-in, there was the expectation (and eventual reality) that the Trump administration’s Executive Order imposing sanctions would be rescinded. Even in that brief period of time, the policy had profoundly detrimental consequences for the ICC’s ability to operate and serious legal questions were raised regarding its constitutionality.

Given the primacy of US banking and financial institutions—as well as the tendency of foreign institutions toward “over-compliance” with US policies—the ability of the Court to keep up its operations was hindered. For example, the Prosecutor’s mandated reporting to the UN was jeopardized amid uncertainty on her permissible travel to New York—even as state officials with outstanding arrest warrants traveled to participate in the same meetings with impunity. Later, reports also surfaced of personal threats against the safety of Madam Fatou Bensouda, then-ICC Chief Prosecutor, and her family.

Flouting of international law and direct opposition to the ICC may already be having a corrosive ripple effect. States Parties may have been emboldened to defy their legal obligation to arrest suspects-at-large, as exemplified by President Macron of France, an ICC State Party, announcing shortly before the last ASP (with its focus on State cooperation), that he would not comply with his country’s obligations regarding the arrest warrant on Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Mongolia, a State Party, recently failed in its obligation to arrest Putin on its soil. The UN Secretary General also has met with Putin while the latter is under indictment, raising questions of “non-essential contacts.” There may not be a direct causal thread between the US actions and those of other States; however, there is a pattern of attrition in respect for the rule of law.

Adam Keith, Senior Director for Accountability at Human Rights First, cogently outlined the harms of sanctions on the ICC prior to passage of the relevant bill by the House of Representatives, which called out its sweeping scope. As Mr. Keith explains, this could include sanctioning close allied nationals and human rights advocates, creating vast liability beyond those specifically sanctioned, as well as a “long and arbitrary ‘do not investigate’ list.” US citizens who represent victims and survivors could be implicated for their work to help achieve justice for perpetrators of atrocity crimes. It would be a terrible irony if a tool designed to penalize gross violators of human rights could instead contribute to their continued impunity.

Why and How to Defend the ICC

The ICC is not beyond reproach. Critiques of selective justice, administrative shortcomings, and politicization have dogged the institution since its inception. As a human invention, it is imperfect, but the Court is still the only hope for many. Today, the ICC, alongside other tribunals, regional mechanisms, and national courts, carries this hope through investigations and prosecutions that can help realize justice for atrocity victims and survivors from Sudan to Myanmar to Ukraine.

For their part, Court officials appear ready to stand against the intimidation. In her address at the 2024 ASP in December, President Akane delivered a stirring alarum: “We firmly reject any attempt to influence the independence and the impartiality of the Court. We resolutely dismiss efforts to politicise our function . . . “The [current] circumstances . . . are only strengthening our determination. We will never give up to coercive measures, threats, sabotage or outrage. The Court, which upholds the principle of the rule of law, will continue pursuing justice and defending the dignity and the rights of victims of atrocities without fear and favour, while ensuring full respect of the highest standards of defence rights.” As objective determiners of fact and rulers on matters of law, judges should never need to make such an appeal; their independence and autonomy must be upheld as sacrosanct. But when they do, their voices must not echo alone but should form the baseline for a chorus. Here, allies of international justice and believers in the rule of law have a critical role to play.

What Can Be Done

In 1995, the organization I now lead (then under a different name) was one of the first members of a group of approximately 25 human rights organizations advocating for a permanent international criminal court to hold individuals to account for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. It worked. That once scrappy outfit is now the formidable Coalition for the ICC (CICC), which boasts thousands of member organizations in 150 countries.

While only organizations are eligible for CICC membership, individuals can actively oppose a misguided policy that undercuts US principles and interests by contacting your representatives directly, through mobilization such as Peace Action has led for a national advocacy campaign. Legal associations also have an important role to play: here, the American Society of International Law, usually laconic on political questions, has stepped up to the plate.

Two lawsuits were filed in US federal courts challenging the previous sanctions. Although they were rendered moot when the Executive Order was rescinded, they may bear revisiting today. In Sadat v. Trump, plaintiffs challenged former President Trump’s executive order authorizing sanctions against people who assist the International Criminal Court in investigating or prosecuting war crimes and other gross human rights violations. The plaintiffs were human rights and legal professionals working with the ICC in ongoing investigations and prosecutions of gross atrocity crimes. They claimed the EO violated the First Amendment and overreached the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). In OSJI v. Donald J. Trump, et al, the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI), with named plaintiffs who are law professors and international legal professionals, claimed violations of their First Amendment rights, as well as arguments around constitutional vagueness violating due process clauses of the Fifth Amendment, as well as other ultra vires violations of executive authority. These legal arguments bear revisiting now with reference to the new sanctions policy.

Conclusion

At an historical moment when the global rule of law is besieged from multiple fronts, institutions like the ICC are needed more than ever to advance human rights protections and the universal goal of preventing future atrocities. The ICC represents and constitutes part of a global system of international justice of which the United States was a chief architect at Nuremberg and beyond. And yet, never since its inception has the Court faced such palpable existential threats that jeopardize the hope of an end to impunity for the most serious crimes of concern to the international community. Sanctions send a signal that could embolden authoritarian regimes and others with reason to fear accountability and seek to evade justice. Such actions jeopardize the ability of desperate victims to access justice, weakens the credibility of sanction tools in other contexts, and places the United States at odds with its closest allies.

Mondial is published by the Citizens for Global Solutions (CGS) and World Federalist Movement — Canada (WFM-Canada), non-profit, non-partisan, and non-governmental Member Organizations of the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Government Policy (WFM-IGP). Mondial seeks to provide a forum for diverse voices and opinions on topics related to democratic world federation. The views expressed by contributing authors herein do not necessarily reflect the organizational positions of CGS or WFM-Canada, or those of the Masthead membership.