by Lawrence Wittner | Dec 14, 2023 | Peace

Although the unfolding humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza has captured the world’s horrified attention, the war in Ukraine has had even more terrible consequences. Grinding on for nearly two years, Russia’s massive military invasion of that country has taken hundreds of thousands of lives, created millions of refugees, wrecked Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure and economy, and consumed enormous financial resources from nations around the world.

And yet, despite the Ukraine War’s vast human and economic costs, there is no sign that it is abating. Russia and Ukraine are now bogged down in very bloody military stalemate, with about a fifth of Ukraine’s land occupied and annexed by Russia.

Meanwhile, polls show that an overwhelming majority of Ukrainians remain determined to continue the struggle to free all of Ukraine from Russian captivity. Indeed, an opinion survey in the fall of 2023 found that 80 percent of Ukrainians polled believed that under no circumstances should Ukraine give up any of its territory.

Similarly, in Russia, polls have found that a majority of the public appears content with the Putin regime’s military conquest of Ukraine and is opposed to any peace settlement that would relinquish Russian control of conquered Ukrainian land. Of course, the accuracy of Russian polls on the Ukraine War remains deeply suspect, for professing opposition to the war could easily lead to arrest, as it did for 20,000 Russians in 2022. Perhaps for this reason, numerous Russians polled refused to answer the question of where they stood on the war. One participant responded: “Thank you for the opportunity not to testify against myself.” In any case, in increasingly authoritarian Russia, public sentiment against war seems unlikely to alter the Putin administration’s determination to triumph on the battlefield.

Admittedly, in the United States, the major supplier of military and economic aid to beleaguered Ukraine, some developments point to declining enthusiasm for that role. The Republican Party has revived its 1930s policy (once termed “isolationism”) of appeasing military aggression by rightwing dictatorships, while leftists with an anti-American slant see a Russian victory as a useful way of somehow destroying “U.S. imperialism.” Nonetheless, unless Donald Trump and his MAGA followers sweep into power in 2024, it seems unlikely that the U.S. government or its NATO partners will entirely abandon Ukraine to a future under the jackboot of Russian military occupation.

Given these obstacles, is there a way to secure a just settlement of the Ukraine War?

There is, but it will take some creative action by the United Nations, the global organization that has been authorized to enforce international security.

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the overwhelming majority of the world’s nations have repeatedly used their participation in the UN General Assembly to condemn the Russian invasion and to call for a just peace in Ukraine. For example, on the eve of the one-year anniversary of the war, the General Assembly, by a vote of 141 nations to 7 (with 32 abstentions), demanded that Russia “immediately, completely, and unconditionally” withdraw its military forces from Ukraine and called for a “cessation in hostilities” and a “comprehensive, just and lasting peace” based on the principles enshrined in the UN Charter. The UN Charter, of course, constitutes international law and bans “the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State.”

Even so, it is the UN Security Council that is tasked with enforcing international security, and Russia has used its veto in that UN entity to block UN action to end the Ukraine War.

The paralysis of the UN Security Council, however, need not continue. As Louise Blais, Canada’s ambassador to the United Nations from 2017 to 2021, has recently pointed out, Article 27 (3) of the UN Charter states that a party to a dispute before the Security Council shall abstain from voting in connection with the dispute. But, when it came to the Security Council’s votes on the Ukraine War, as Blais noted, “none of the 10 elected Security Council members had the courage, vision or backing to put forward a resolution” demanding abstention. According to Blais, the unwillingness of the four other veto-wielding members (Britain China, France, and the United States) to avoid a crippling Russian veto and, thereby, empower the Security Council to act, reflected their “zero interest in supporting such a move for fear it would limit their own power in the future.”

But there is ample precedent for limiting the veto in this fashion. The United Nations has a history of veto-wielding nations abstaining from Security Council voting when they are parties to a dispute. As Blais observes, between 1946 and 1952, Security Council members “regularly adhered to the obligatory abstention rule.” Only in later years did the five permanent Security Council members curtail the application of this practice.

In short, based on both international law and precedent, the UN Security Council has the authority to impose a settlement of the disastrous Ukraine War. What kinds of international action this would require would need to be determined by the world organization, just as the final terms of a peace agreement would ultimately need to be accepted by the contending parties. But, given the overwhelming support in the UN General Assembly for the withdrawal of Russian military forces from Ukraine and for a lasting peace agreement, such a peace settlement is likely to be a just one.

At the least, this would be a far better method of dealing with international conflict than the current full-scale war currently raging in Ukraine. And it could serve as a model for resolving other intractable disputes, such as the brutal Israel-Palestine conflict, as well.

This article was originally published in International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War’s Peace and Health Blog

Image Credits: UN Photo/Evan Schneider

by David Gallup | Dec 8, 2023 | World Citizen

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the World Citizenship Movement (WCM).

As a response to the devastation of World War II, the drafters of the UDHR sought to ensure that human rights would be protected by the rule of law. The Declaration provides a statement of our civil, cultural, economic, political, and social rights.

The WCM links our universal rights to our identity as citizens of the world. Former WWII bomber pilot Garry Davis gave up his US citizenship in favor of world citizenship, launching the World Citizenship Movement in 1948 to promote peace and human unity.

The UDHR and the WCM offer a framework of universal rights and universal identity to achieve the peaceful and governed world envisioned in 1948 by both the drafters of the UDHR and World Citizen Garry Davis.

Although we have enumerated our rights over the past 75 years, we have not yet fully implemented them. To paraphrase Rousseau from The Social Contract, humans are born free, but everywhere we are in chains. We have empowered a governing system — the nation-state — that because it is partial, can never fully affirm our rights and duties. The nation-state system where states maintain absolute sovereignty enslaves us to corporate interests and national security at the expense of human needs and world security.

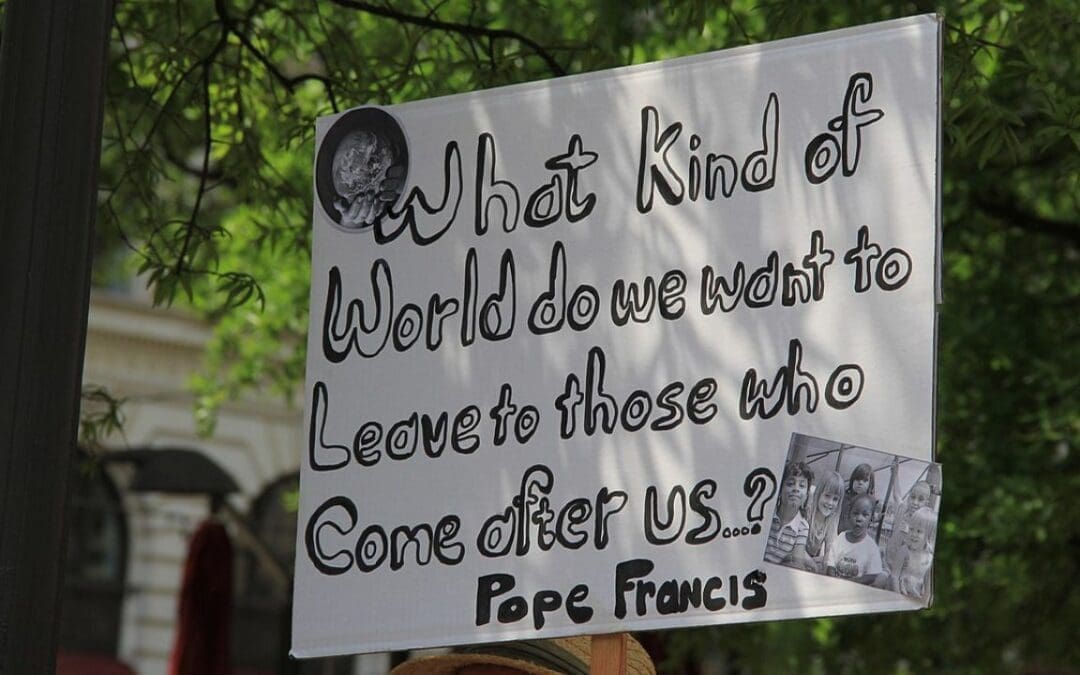

As we celebrate how far humanity has come in the past seventy-five years, and simultaneously recognize the many existential challenges we currently face — war, climate destruction, injustice – let’s consider what kind of world we want for humanity in 2098, seventy-five years from now on the cusp of the 22nd Century.

Over the next 75 years, we must build a human rights institutional architecture that affirms our universal rights. That framework must be built on the global rule of law, world law that applies to everyone, everywhere. We must recognize the importance of seeing ourselves as world citizens and must legalize this status.

To achieve the peaceful and just world that the drafters of the UDHR and the advocates of the World Citizenship Movement envisioned, we must build the law, citizenship and governing structures at the world level that will help humans live together peacefully with each other and sustainably with the earth based on the principles of universal rights and universal citizenship.

How do we arrive at 2098, 75 years from now, having built a peaceful, just, sustainable, and united world?

- The UDHR must become a universal bill of human rights incorporated into a world constitution legally binding on everyone, everywhere. This would ensure that all governments, ranging from local town councils and nation-states to the world federal government would place rights above self-interest and the force of law above the law of force.

- World citizenship must become a recognized legal status for everyone, everywhere. This would mean that no one would be stateless anymore. Everyone would be able to exercise all rights no matter where they are or where they go throughout the world.

- We, humanity, must create a World Parliament to participate in governing the world as one united planet. This would put the rights of individuals above the power of states.

- A World Court of Universal Rights must be established where individuals and groups could seek redress when local judicial systems fail them. A global judicial system with subsidiary regional courts would provide venues for people to resolve conflicts peacefully.

- To secure our peacebuilding efforts, we must outlaw war and weapons manufacturing. We must use resources sustainably for peaceful means. Because war and its preparation are the biggest wasters of resources, we need to develop peace and indigenous-based economies that will protect the Earth and ensure humanity’s survival.

Ultimately, we must fulfill human needs, affirm rights, resolve conflict, and protect the environment. We must build an ethical identity and governing system that allows us to accomplish these human and planetary requirements and manage our human and environmental interactions equitably and peacefully.

In 1948, the UDHR and the World Citizenship Movement provided a vision of a united world as an alternative to absolute national sovereignty that perpetuates war and continues to fracture humanity. The UDHR and world citizenship together provide the ethical framework we need to have a thriving Earth community in 2098.

By fully implementing the Declaration of Human Rights and world citizenship, in 75 years from now, we will have transcended the “Divide and Conquer” approach in favor of a “Unite and Prosper” paradigm.

by Augusto Lopez-Claros and Daniel Perell | Oct 29, 2023 | UN Reform

It seems each day provides us a fresh reason for pessimism. A new demonstration of the fraying social contract, especially at the international level. The pillars upon which the international order was built seem to be rapidly deteriorating—from territorial integrity to the laws of war to the breaking of promises—and we find ourselves asking: what is to be done? There is no need to provide a comprehensive summary here of the risks we face; compelling diagnoses exist of what ails the world and there is no shortage of sensible prescriptions. The UN Secretary General’s Our Common Agenda is a good recent example as are many other reports and analyses with a narrower focus, touching upon issues of climate and the environment, security, poverty and inequality, financial sector vulnerabilities, and other such risk factors.

There is also growing acceptance of the view that these problems are generally global in nature; they are transnational. Solutions to them can best be framed in a context of much stronger international cooperation. It is for this reason that the debate about actions to confront them often ends up with a focus on the system of multilateral institutions that emerged out of the ashes of World War II.

UN Reform a nonstarter?

One aspect of this debate is whether, against the current geopolitical background, it would even be prudent to talk about reforms to our global governance architecture. With the “abysmal political climate for international cooperation, with deep rifts and mistrust” some argue that “reform is a nonstarter,” that it is Alice in Wonderland to “discuss reforming the UN while ignoring the brutal contemporary political realities.”

Implicit in this position is the notion that time is on our side, that we can afford to wait for the ‘right’ geopolitical moment. And, until the stars align again, our task lies in making minor adjustments. Secretary-General Kofi Annan told the General Assembly in 2003 “we have reached a fork in the road.” This thought has been repeated countless times by other Secretaries-General, by well-meaning heads of state and, it is assumed, will continue to be repeated through 2045, the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the UN Charter.

But insights coming from systems science about the breaching of planetary boundaries—to take just one example—demonstrate that time is not on our side, that we have a rapidly narrowing window of opportunity to address and hopefully mitigate the worst effects of the coming environmental calamities. Or, likewise, to reduce the likelihood of the use of nuclear weapons in one of the many unresolved conflicts bubbling around the world. What, then, is to be done?

Three viable paths

There seem to be three viable paths, which can be pursued concurrently. The first path is to recommit ourselves to the system we have. There are tremendous benefits to this—most notably that it would be a return to consensus. At this moment of great crisis, there is a legitimate case to be made that the safest route is the surest route—at least in the short term. However, that is also a limiting prospect and runs the risk of determining that the best we can do is to continue doing what we have already done. Perhaps more importantly, if we are conscious that the system as it stands is increasingly insufficient, by choosing only this path we are in a way admitting defeat at the outset.

The second course of action is to take the model we have and innovate. This is the course of action offered through the upcoming Summit of the Future and its attendant proposals including a New

Agenda for Peace, proposals for financial architecture reform, and even Article 109. There is significant merit in this course of action, as well: it offers an opportunity for questioning the structures we have without undoing the progress they have made. In other words, it allows for organic growth. Yet, there are risks here, too—in that we could end up investing significant time and energy to perpetuate a system ill-suited to our interconnected reality; or that we achieve only marginal progress, or, worse still, the process results in greater political fragmentation and mistrust.

The third course of action is a deeper exploration into the persistent challenges underlying our current systems and a search for new solutions. Essentially, questioning underlying assumptions and finding new answers. This course of action excites us most—in large part because we do not believe that the current frameworks are sufficient for the world of today, let alone tomorrow. In other words, when we imagine a century ahead, we just can’t picture a global governance system where Member States are expected, even required, to prioritize their domestic concerns when discussing international matters. We can’t imagine that a successful governance system would continue to prioritize a profit motive, a power motive, over the wellbeing of citizens and nature. Yet the system we have (even if modified as in option two) does just this. We will also be the first to admit that this may not be the most politically realistic course for today, but it will one day be the path we must choose. Why not begin it now given its far-reaching implications?

We do not need to choose merely one of these three options. We are at a moment where many opportunities open before us. The international order is struggling under the weight of the crises we face—both new and old. Let us use this consensus as a starting point to commit to what we have, to see what meaningful change can come from the processes in progress, and to rethink the current order from our starting assumptions. In essence, a little bit of each viable path is the ultimate expression of the precautionary principle for global governance.

Overcoming paralysis

One problem with concluding that the current political impasses make UN reform a nonstarter is that it leads to paralysis. It results in proposals that are the intellectual equivalent of rearranging the deckchairs as the ship is sinking. We are not suggesting ignoring the political realities of this moment but trying to see what the future holds. One day, we will need to move beyond traditional paradigms, beyond “reinforcing the crumbling foundations” of the current system. Humanity will need to articulate a new architecture, better suited to the needs of a rapidly changing humanity.

Importantly, it is not only governments who can advance this conversation—in fact this might be a key to overcoming some of the seemingly intractable obstacles to reform. As was noted in A Second Charter: Imagining a Renewed United Nations, numerous global governance innovations over the past quarter century were not initiated by governments. They started with civil society organizations: the Land Mines Treaty, the creation of the International Criminal Court, and the adoption of the Treaty on the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons, to cite some recent examples. At a later stage, many governments adopted them. This is the “new diplomacy” in action.

At the end of World War II, and because of the destruction created by that conflagration, humanity had an opportunity to imagine something better suited to the needs of, in particular, the European continent. If in 1945 one had ventured to suggest that within a generation Europe would be advancing a project of economic and political integration, that by the late 1970s there would be direct elections for members of an increasingly influential European Parliament, and that by end of the century the broad parameters of monetary policy would be set by a European Central Bank based in Germany managing a single currency, one might have been accused of “Wonderland thinking”. And yet, it was the very political turmoil of that moment which allowed for this evolution to take place.

Today, we cannot afford to wait for what is called a “San Francisco” moment. Recall how that gathering came only after a global catastrophe prompted humanity to dare to think differently and engage in a reform process. Yet, today’s generation is carrying the legacy of the imperfections bequeathed to it. Let us not wait for another catastrophe before we engage in meaningful reform processes. In addition to recommitting to promises made, in addition to technical modifications, let us take that leap of imagination necessary to prevent future global catastrophes. Who knows, perhaps in a few decades, like the European case, future generations will be amazed at what we were able to achieve.

This article was originally published in Global Governance Forum’s blog.

Image Source: Palácio do Planalto from Brasilia, Brasil, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by David Oughton | Oct 28, 2023 | Climate Justice

Pope Francis released this apostolic exhortation “to all people of good will on the climate crisis” on October 4, the feast day of St. Francis of Assisi. Its Latin title refers to the message of St. Francis to “praise God for all of God’s creatures.” (#1) This letter to the world is an addendum to his 2015 encyclical “Laudato Si” (“Praise Be,” the beginning words of a canticle by St. Francis). That encyclical is known as “On Care for Our Common Home.”

Pope Francis decided to write Laudate Deum because “climate change is one of the principal challenges facing society and the global community” (#3) but he is gravely disappointed that “our responses have not been adequate.” (#2) The acceleration of global warming is evident now. “Despite all attempts to deny, conceal, gloss over or relativize the issue, the signs of climate change are here and increasingly evident.” (#5)

According to Pope Francis, “it is no longer possible to doubt the human–‘anthropic’–origin of climate change.” (#11) He says that it is a fact that the average global temperature has risen dramatically with the increase use of fossil fuels. The consequence is the melting of glaciers and the polar regions, the acidification of the oceans, and the rising of sea level. He concludes that “the change in average surface temperatures cannot be explained except as the result of the increase of greenhouse gases.” (#14) He believes that some effects of the climate crisis are already irreversible.

What has gotten us to this point? Pope Francis argues that a growing technocratic paradigm that exploits nature because of unbridled power and economic ambition is the underlying issue. Humans have forgotten that we are part of nature and that how we interact with the rest of nature affects our future. Therefore, “we need to rethink among other things the question of human power, its meaning and its limits.” (#28) We need to reassess an economic mentality about maximum gain at minimal cost because such an attitude has serious consequences about care of our common home and care for the poor and needy.

The 2015 Paris Agreement has ambitious goals that are not currently being met. Pope Francis hopes that the next climate conference will lead to the “necessary transition towards clean energy sources such as wind and solar energy, and the abandonment of fossil fuels.” (#55)

Pope Francis also addresses the weakness of international politics. Individual nations acting alone cannot solve the climate crisis or any of our other global problems. He says that we need multilateral agreements based on the principle of subsidiarity. Solving global problems requires “establishing global and effective rules” (#42) and “increased ‘democratization’ in the global context.” (#43)

The reason why humanity has been unable to solve major global problems is because of our current international system of sovereign nation-states. International law is a system of non-binding treaties. No nation is required to become a party to any international treaty. National governments that enter into treaties can withdraw from them or ignore them based on their perceived national interest.

In Laudato Si, Pope Francis agreed with several previous popes that “there is urgent need of a true world political authority.” (#175) Many Catholic leaders have been arguing that outlawing war and genocide as well as solving global problems such as climate change will require a truly effective democratic world public authority that can create and enforce world laws and prosecute individuals who violate them. Until such a system is created, Pope Francis says that it is imperative that national governments become parties to effective environmental treaties and that they keep their treaty obligations.

With this letter to the global community, Pope Francis continues his warning about the existential crisis caused by climate change. He emphasizes the physical and spiritual dimensions of this crisis. This letter needs to be studied by members of the world community because it concerns the future of our common home.

Image credit: Dcpeopleandeventsof2017, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Lawrence Wittner | Oct 25, 2023 | Peace

In December 1934, Arthur Henderson, a leader of the British Labour Party, declared in his speech accepting the Nobel Peace Prize that the immense human suffering caused by World War I “led to the very clear realization that international anarchy must be abandoned if civilization was to survive.”

Unfortunately, that realization did not go very far or very deep. Although, since that time, international law has been refined, nations remain far from adhering to its provisions or accepting its enforcement by the United Nations.

The Arab-Israeli Conflict

The lengthy, bloody conflict between the Israelis and their Arab neighbors provides a dramatic illustration of this point.

On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted a plan to replace the British Mandate in Palestine with a partition of that land between a Jewish state and a Palestinian state. The UN decision was fiercely resented by the surrounding Arab nations, which launched a war against the new Jewish state, Israel—a war from which Israel emerged victorious in 1948.

This victory did not end the violence, however, or the violations of international law. Having fled abroad from the fighting in 1948, over 700,000 Palestinians, in contravention of international law, were denied the right to return to their homes in Israel. Egypt, which, in 1956, had agreed under UN pressure to the demilitarization of the Sinai Peninsula, expelled UN observers in 1967, massed its troops on Israel’s border, and together with Jordan, readied itself to invade Israel. In turn, Israel launched devastating attacks on Egyptian, Jordanian, Syrian, and Iraqi military forces. Victorious in this Six-Day War, Israel gained control of the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights.

Over the ensuing decades, numerous violent clashes followed, with Israel, now the dominant military power in the region, defeating Arab and Palestinian resistance. Meanwhile, Israel defied international law by continuing to occupy the territory conquered in 1967, colonizing it with Jewish settlements, and violating the human rights of its Palestinian residents. For their part, Hamas terrorists, dedicated to unremitting war against Israel, committed horrendous war crimes against noncombatants in clear violation of the 1949 Geneva Conventions. When the Israeli government deprived Gaza’s civilian population of food, water, and other essentials of survival, it, too, defied international law.

The Russia-Ukraine War

The Russian invasion of Ukraine provides another clear example of flouting international law. Article 2, Section 4 of the UN Charter prohibits the “use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” Ukraine had been an independent, sovereign nation since 1991, when the Soviet Union authorized a referendum on whether it wanted to become part of the new Russian Federation or to become independent. In the balloting, 90 percent voted for independence, which was formally accepted. Three years later, in the Budapest Memorandum, the Russian government pledged to “respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing borders of Ukraine” and to “refrain from the threat or use of force” against that nation.

Nevertheless, in 2014 the Putin regime drew upon Russian military power to seize and annex Crimea in southern Ukraine and to arm pro-Russian separatists and unleash its own thinly-disguised military forces in eastern Ukraine. In February 2022, the Russian government, determined to seize full control of Ukraine, launched a massive military invasion. Although fierce resistance by the Ukrainians prevented a complete Russian takeover, that September Putin announced the annexation of four additional regions of Ukraine, declaring that Russia would never surrender them.

Most of the world’s nations assailed this behavior as a flagrant violation of international law. In March 2014, after a Russian veto blocked a UN Security Council rebuke, the UN General Assembly voted by an overwhelming margin to condemn the Russian action that year. In March 2022, amid a new Russian veto of UN Security Council action, the UN General Assembly roundly condemned the full-scale Russian invasion by a vote of 141 to 5 (with 35 abstentions), while the International Court of Justice, the world’s highest judicial authority, voted by 13 to 2 (with Russia’s judge casting one of the negative votes) that Russia should “immediately suspend” its invasion. That October, the UN General Assembly, by a vote of 143 nations to 5 (with 35 abstentions), called on all nations to refuse recognition of Russia’s “attempted illegal annexation” of Ukrainian territory.

The Renewed Nuclear Arms Race

Perhaps the most chilling manifestation of international anarchy is the renewed nuclear arms race. Recognizing the potential for worldwide destruction in a nuclear war and pressed for action by an uneasy public, the nations of the world did, eventually, sign nuclear arms control treaties. Among these agreements was the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty of 1968, in which non-nuclear nations pledged to forgo building nuclear weapons, while the nuclear nations agreed to divest themselves of their nuclear arsenals. Nevertheless, in recent decades, additional nations have become nuclear powers, while existing nuclear powers have scrapped previous nuclear disarmament agreements. Symptomatically, the nuclear powers oppose the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which became international law in 2021.

Indeed, all the nuclear nations are currently engaged in nuclear weapons buildups―planning and developing new, more efficient weapons of mass destruction. Some government officials, among them Vladimir Putin, publicly threaten to launch nuclear war against nations opposing their international policies.

The planet faces a perilous future, indeed, particularly when one considers that, as of early 2023, it was undergoing the largest number of violent conflicts since World War II.

Global Governance

Against this backdrop, it’s tempting to conclude that, thanks to the apparently ungovernable nature of the world, the annihilation of civilization is inevitable. But is the world ungovernable―or merely lacking an effective government?

Given the fact that the United Nations was created to guarantee international security, a logical solution to the problem of effective governance is to strengthen the ability of the world organization to enforce international law. By curbing international anarchy, this action would prevent marauding nations and armed bands alike from indulging their worst impulses. It would also significantly enhance the prospects for peace, justice, and human survival.

Image Credits:

Håkan Dahlström from Malmö, Sweden, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Lawrence Wittner | Sep 27, 2023 | UN Reform

Addressing the UN Security Council on September 20, 2023, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky delivered a heartfelt plea “to update the existing security architecture in the world, in particular, to restore the real power of the UN Charter.”

This call for strengthening international security under the aegis of the United Nations makes sense not only for Ukraine―a country suffering from brutal military invasion, occupation, and annexation by its much larger, more powerful neighbor, the Russian Federation―but for the nations of the world.

The Rise of the United Nations

For thousands of years, competing territories, nations, and empires have spilled rivers of blood and laid waste to much of the world through wars and plunder. Hundreds of millions of people have died, while many more have been horribly injured or forced to flee their shattered homelands in a desperate search for safety. World Wars I and II, capped off by the use of nuclear weapons to annihilate the populations of entire cities, brought massive suffering to people around the globe.

In 1945, this mad slaughter and devastation convinced far-sighted thinkers, as well as many government leaders, that human survival was dependent upon developing a framework for international security: the United Nations. The UN Charter, adopted in a conference in the spring of that year in San Francisco by 50 Allied nations, declared that a key purpose of the new organization was “to maintain international peace and security.”

The UN Charter, which constitutes international law, included provisions detailing how nations were to treat one another in the battered world emerging from the Second World War. Among its major provisions was Article 2, Section 4, which declared that “all members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” Furthermore, Article 51 declared that “nothing in the present Charter shall impair the inherent right of individual or collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against a member of the United Nations.”

The Role of the Security Council

Although the UN Charter provided for a General Assembly in which all member nations were represented, action to maintain international peace and security was delegated primarily to a UN Security Council with fifteen members, five of whom (the United States, the Soviet Union, China, Britain, and France) were to be permanent members with the right to veto Security Council resolutions or action.

Not surprisingly, the right of any of these five nations to block Security Council peace efforts, a right they had insisted upon as the price of their participation in the United Nations, hamstrung the world organization from enforcing peace and international security on numerous occasions. The most recent instance has occurred in the case of the Ukraine War, a conflict in which, as Zelensky lamented, “all [Security Council] efforts are vetoed by the aggressor.” As a result, the United Nations has all too often lacked the power to enforce the principles of international law confirmed by its members and enshrined in its Charter.

Some people are perfectly content with the weakness of the United Nations. Fierce nationalists, including some Right-Wing actors, are contemptuous of this or any international security organization, and many would prefer its abolition. Others have little use for the United Nations but, instead, place their hopes for the maintenance of international peace and stability upon public and governmental acceptance of great power spheres of influence. Meanwhile, a segment of the international Left ignores the United Nations and insists that world peace will only be secured by smashing “U.S. imperialism.”

Sadly, those forces opposing international organization and action fail to recognize that their proposals represent not only a return to thousands of years of international strife and mass slaughter among nations, but, in today’s world, an open door to a nuclear holocaust that will end virtually all life on earth.

Proposals to Strengthen the United Nations

Compared to this descent into international chaos and destruction, proposals to strengthen the United Nations are remarkably practical and potentially effective. Zelensky has suggested empowering the UN General Assembly to overcome a Security Council veto by a vote of two-thirds or more of the Assembly’s nations. In addition, he has proposed expanding the representation of nations in the Security Council, temporarily suspending membership of a Security Council member when it “resorts to aggression against another nation in violation of the UN Charter,” and creating a deterrent to international aggression by agreeing on the response to it before it occurs.

Of course, there are numerous other ways to strengthen the United Nations as a force for peace and to help ensure that it works as an effective international agency for battling the onrushing climate catastrophe, combating disease pandemics, and cracking down on the exploitative practices of multinational corporations. Its member nations could also rally behind the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (still unsigned by the nuclear powers), agree on a UN program to handle the burgeoning international refugee crisis, and provide the world organization with substantially greater financial resources to reduce global poverty and mass misery than it currently receives.

Indeed, the horrific Ukraine War is but the latest canary in the coal mine―the danger signal that people of all nations should recognize as indicating the necessity for moving beyond national isolation and beginning a new era of global responsibility, cooperation, and unity.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons