by Donna Park | Jul 12, 2024 | Peace

Although I am now a mother and grandmother, when I was in college in the early 1970s I protested against the Vietnam War. Thankfully, all the protests I joined stayed peaceful. I was lucky I wasn’t at Kent State University, where, on May 4, 1970, four unarmed student protesters were shot and killed and another 9 were wounded by the Ohio National Guard, which had opened fire on them with high-powered rifles.

Even though the demonstrations in which I participated were peaceful, we were often told we were “anti-American” if we were against war. “Love it or leave it,” we were told. My dad was a veteran of World War II. He wasn’t happy with my participation in the protests, and he was especially upset when I wrote a letter to the editor of my hometown newspaper, publicly stating I was against the war. Indeed, he threatened to pull me out of college.

But my friends and I were not anti-American. We were anti-war…and many of us still are. I love America, but I do not love the war machine that makes some people wealthy while causing widespread death, suffering, and environmental disasters. I am against war, but still insist we care for our veterans who are injured physically and emotionally by war.

The traditional argument for war is that it makes us safe and secure. But it is hard to see how any war in this century has made us either safe or more secure. One could even argue that wars are making us less secure by creating more enemies. In my opinion, we need more Americans standing up and saying we are against war and need to find a better way to make us safe and secure.

So I am proud of the college students who have protested peacefully against the war in Gaza. Just as I was called anti-American in the 1970s, many of them are being called anti-Semitic 50 years later. I believe the vast majority of them are not anti-Semitic but, rather, are anti-war, against the killing of civilians (especially children), and opposed to the destruction of people’s homes and hospitals. In fact, there are many Jewish students who are protesting the war. Some of them are facing harsh criticism from their parents for failing to defend the state of Israel. I applaud these students for holding onto their convictions that war and killing are wrong, even in the face of criticism from home.

I would like to encourage today’s students―and people in general― to promote an alternative way to solve the conflicts among nations that sometimes lead to wars. Within the United States, we avoid violence and wars among our states by relying on judicial action to resolve disputes. The same peaceful settlement of disputes is possible on the international level through the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the principal judicial organ of the United Nations.

Currently, though, only 74 nations accept the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ. Legal Alternatives to War (LAW Not War) is a recently-launched global campaign to extend this Court’s jurisdiction. The principal objective of the campaign is to increase the number of States accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ, with the goal of achieving universal acceptance of jurisdiction by 2045, the 100th anniversary of the United Nations. In addition, the campaign works to enhance ICJ jurisdiction by promoting greater use by UN bodies of the option to request Advisory Opinions from the ICJ, such as the current requests for opinions on State responsibility for climate change, and encouraging disputing States to make more frequent use of the option of taking cases to the ICJ by mutual agreement.

Relying on the force of law instead of the law of force is a better way to address conflicts among nations and, in this fashion, keep us all safe and secure.

by Sovaida Maani Ewing | Jul 2, 2024 | Peace

We live in a global family of more than 190 countries. Disputes and squabbles inevitably arise in all families; what matters is how we settle them. Just as immature families might see bullying and violence, at the global level we see countries threatening and waging war, paying dearly in unnecessary death and suffering. By contrast, a mature family resolves its disputes peacefully, often with the help of a dispassionate third party. Providing the world family such a dispassionate dispute settler was the driving purpose for creating the International Court of Justice (ICJ) (colloquially known as the World Court) in the aftermath of the Second World War. Unfortunately, the Court suffers from fundamental flaws that have hindered its ability to preserve peace and avoid violent conflict between countries.

The first flaw is that the World Court does not have compulsory jurisdiction over all disputes arising between countries. When such disputes arise, it can only obtain jurisdiction in one of three ways: if a country chooses to grant it permanent jurisdiction for all disputes (although even this jurisdiction can be limited in time or type of dispute by “reservations” registered by a state); if a country grants it ad hoc jurisdiction over a specific issue; or if the Court is granted jurisdiction under the terms of a treaty agreed between countries. In other words, the World Court does not automatically have jurisdiction over all disputes between states; the disputing countries must have opted to grant it such jurisdiction.

It is obvious that such a system is untenable if we are to have any prayer of maintaining law and order. Consider the uproar that would ensue were we to propose a similar system domestically, in our localities, cities, and countries. None of us would stand for it. Law and order would be impossible to maintain. Would anyone who commits murder opt in to trial before a court? If we are serious about ending war, and about resolving our intra-state disputes amicably, it is high time that we reform our international system of justice and the rules governing it. All countries must agree to renounce war as an instrument of resolving disputes and instead submit themselves to compulsory jurisdiction of the World Court.

We see the urgent need for compulsory jurisdiction in countries’ tortured work-arounds to obtain justice in major breaches of world peace today. One example is the recent case brought by South Africa against Israel about the latter’s treatment of residents of Gaza. In a properly functioning system, South Africa should have been able to challenge potential violations of the Geneva Conventions for the treatment of non-combatants in war in the World Court. Yet, it resorted to bringing this case under the Genocide Convention instead, for two reasons. First, Israel had not granted the Court either permanent or ad hoc jurisdiction over the case. Second, the Geneva Conventions do not confer jurisdiction upon the Court, whereas the Genocide Convention does. This sort of work-around is not unusual: countries resort to suing each other under the Genocide Convention, or the Convention against Torture, or the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, because they each grant the World Court jurisdiction. By contrast, none of the International Humanitarian Law Treaties, like the Hague Conventions or Geneva Conventions, confer mandatory jurisdiction.

But this work-around leaves the Humanitarian Law Treaties a dead letter and reduces the chances for international justice to be done, at the ultimate cost of failing to resolve international disputes. For the Genocide Convention outlaws an extremely serious crime that, appropriately, requires South Africa to meet an extremely high and difficult standard, as demonstrated by the Court’s prior case law. For example, when Croatia took Serbia to the World Court for genocide, the Court in its 2015 decision found that Serbia had engaged in actions that satisfied the physical element of the crime of genocide, but there was insufficient evidence of mental intent to commit genocide—the second element required to prove the crime of genocide. Moreover, it found that while Serbia had engaged in the forced displacement of large numbers of Croats, such actions did not rise to the level of genocide. These actions might well have violated the Geneva Conventions’ rules for treating non-combatants, but the Court did not have jurisdiction to decide. The South Africa / Israel case will face the same hurdle and similarly risks leaving bitterly disputed events unadjudicated by peaceful means.

The second fundamental flaw in the design of the World Court is that, although its decisions are binding under Article 94 of the UN Charter, no effective means have been provided to enforce them. Consequently, nations often disregard the decisions of the Court with impunity. It is crucial that we apply all the ingenuity with can muster to come up with an effective system of enforcement or else resign ourselves to a world in which nations have carte blanche to act in defiance of a rules-based order. In the case of our murderer, even if he could be tried and convicted, it would be nonsensical to expect him to enforce his own sentence.

Recent decisions of the World Court, including its recent ruling demanding that Israel halt its military assault on Rafah and its 2022 ruling directing Russia to immediately suspend its military operations in Ukraine, demonstrate the bankruptcy of our international judicial system. In both cases, defendants have been able to flout the Court’s rulings with impunity due to the absence of an adequate enforcement capability.

The time has come to cure these defects in our international system of justice by amending the UN Charter to grant the World Court compulsory jurisdiction over all disputes between nations and to create a viable mechanism for enforcing its judgments against recalcitrant states.

Image source: International Court of Justice; originally uploaded by Yeu Ninje at en.wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

by John Vlasto | Jun 22, 2024 | World Federation

Most people do not benefit from wars or from degradation of our global environment. Allowing them to continue year after year carries existential risk through unconstrained conflict or environmental catastrophe. So, given the fact that the risk far exceeds the reward, why don’t we stop this self-destructive behavior?

The reason is that our global institutions are inadequate to the task. The United Nations was founded after the Second World War as a club of sovereign nations, with the five winners of that long-ago conflict given a veto in the Security Council. As the renowned physicist Albert Einstein (a founder of the movement we continue today) warned at the time, “With all my heart I believe that the world’s present system of sovereign nations can only lead to barbarism, war, and inhumanity.” And so it has proved. War, inhumanity, and barbarism towards our environment continue unabated.

The solution is to create global governance that is fit to handle modern challenges – governance that is effective, equitable, accountable to the people, and strictly limited to global issues that are beyond the reach of individual nations, such as the planetary environment, pandemics, and war.

We know how to do this. The European Union provides one example, the United States of America another. In 1788, George Mason, speaking against the state of Virginia joining the newly proposed U.S. federal government, asked: “Is it to be supposed that one National Government will suit so extensive a country, embracing so many climates, and containing inhabitants so very different in manners, habits, and customs?” As it turns out, yes – despite many challenges, under its federal government the U.S. has grown to be one of the richest and most powerful countries on Earth. The European Union, too, has had its challenges, but is unquestionably preferable to the two world wars that catalyzed its creation.

A federal system, with governance at different levels to tackle challenges at different levels from local to global, has been proposed for generations. President Harry Truman remarked in 1945: “If Kansas and Colorado have a quarrel over a watershed they don’t call out the national guard in each state and go to war over it. They bring suit in the Supreme Court and abide by its decision. There isn’t a reason in the world why we can’t do that internationally.” Such a federal system works in the United States, it works in Europe, it works in many diverse countries and regions around the world, and it could work equally well at the global level.

A global federation of nations would not threaten national sovereignty over national concerns, it would enhance it. In a rules-based international order, nations would be free to do their own thing, subject to not harming others. In our current system, where multinational corporations run rings round national governance, nations are forced into a damaging race to the bottom. No country can afford to move first on reducing carbon emissions when other countries can simply freeride. It is a classic tragedy of the commons. Such tragedies are resolved by agreeing to and enforcing rules that serve the common good.

All this is known, which begs the question why nothing is done. Recently I asked this question of an experienced UN diplomat. Did he think that humanity is taking an existential risk with its future? Yes. Is the solution to create more effective, equitable and accountable global governance? Yes. How? To which he replied “I despair” – not the answer I was looking for. When pushed, he quoted what is known as Juncker’s Curse (named after a former European Commission president): “We all know what to do, but we don’t know how to get re-elected once we have done it.”

Although there are many politicians who know that we need to strengthen global governance to tackle urgent global challenges, the people are not demanding it. People are demanding a ceasefire in Gaza, preservation of the Amazon rainforest, and lower carbon emissions. But the common thread – strengthening global governance – so that countries can go to court to settle their differences rather than resort to war, can put a global price on carbon so there is a financial incentive to preserve the rainforest and lower emissions – this is not widely perceived or, therefore, demanded.

If you agree with this analysis – that the solution to the existential global challenges we face is to create global governance that is effective, equitable and accountable, while protecting national sovereignty over national issues – then the best thing you can do to save humanity from itself is to promote this understanding. Talk to your family and friends. Write to your political representatives, demanding meaningful engagement with current international governance institutions, and calling for a new and reformed global system. Get involved in the campaign to strengthen global governance towards democratic world federation.

Many Americans are already involved in this campaign through Citizens for Global Solutions, the U.S. member organization of the World Federalist Movement.

If people demand the global governance we need, then politicians can act. If politicians do not act soon, it may be too late.

by Sovaida Maani Ewing | Jun 18, 2024 | Disarmament

The threat of nuclear war is at the highest level it has been since the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. However, there is a crucial difference: in 1962, most of us were alert to the threat and its existential nature. Today, by contrast, many of us are oblivious to our history or have simply forgotten it, which poses a huge danger: that of sleepwalking our way into a nuclear war with catastrophic consequences for our country and all of humanity.

This danger is exacerbated by three factors.

The first is the proliferation of nuclear arms and the renewed interest on the part of non-nuclear weapons states to acquire nuclear weapons. The war in Gaza has stirred fears that Iran will race for the bomb and join the nuclear weapons’ club. There are good reasons for such a fear: Recent reports quote the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as saying that Iran is now enriching uranium up to 60 percent, considerably more than the 3.67% permitted under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The IAEA also believes Iran already possesses enough fissile material to make three nuclear weapons. Moreover, the breakout time (the time required to produce enough fissile material at the 90 percent concentration needed for nuclear weapons, not taking into account the time needed to build a deliverable nuclear warhead) is now zero. The fact that the Iran has prevented the IAEA, the world’s nuclear watchdog, from properly monitoring its nuclear activities since early 2021 only exacerbates these concerns. Added to all this are Iran’s own threats that she will reconsider her nuclear stance if her nuclear facilities are threatened.

These fears have a potentially cascading effect: they are likely to spur other countries in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia and the UAE, to seek nuclear capabilities of their own starting with civilian capabilities. Indeed, Saudi Prince Mohammad has already stated that were Iran to build nuclear weapons, Saudi would follow suit. Alas, the more nuclear weapons the world has, the greater the chance they will be used intentionally or accidentally.

A similar scenario is playing out further afield in Asia where China’s assertion of territorial claims to disputed islands in the South China Seas like the Paracels and Spratlys and their adjacent waters rich in reserves of natural resources and its claims to the islands of Senkaku/Diaoyu in the East China Sea, coupled with China’s stated desire to absorb Taiwan, are making other countries in the region fearful of China’s power. Japan and South Korea are particularly nervous, especially given the nuclear threat from North Korea. Their fears have been exacerbated by America’s uneven support of Ukraine in the face of Russian territorial aggression. Even though the United States is bound by a trilateral cooperation agreement to defend Japan and the Republic of Korea under its nuclear umbrella they are worried that the support they have been promised may not be forthcoming. These factors taken together are leading both countries to float the idea of acquiring their own nuclear weapons.

The second factor exacerbating the threat of nuclear war is that the guardrails in the form of a treaty regime so painstakingly crafted by the international community designed to reduce the number of nuclear weapons have been crumbling. The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty collapsed in 2019. The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty is defunct; and while the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START Treaty) — the last Treaty governing nuclear weapons between the U.S. and Russia– is theoretically in effect until 2026, Russia has suspended its participation in the Treaty and has allegedly not complied with her obligations under it since 2023.

The third factor enhancing the threat of nuclear war is the escalating rhetoric of countries like Russia. In early May of this year, Russia sent a clear warning that its arsenal of nuclear weapons was always in a state of combat readiness and announced that it would be holding military drills with troops based near Ukraine to prepare for the possible use of tactical nuclear weapons. This was Russia’s most explicit threat to date that it might use such weapons in Ukraine.

The combination of these three factors should serve to wake us up to the reality facing us before it’s too late. We can no longer afford to be complacent about the dangers of nuclear war, especially as we know, from past experience, that conflicts can escalate rapidly, spin beyond our control and lead to unintended consequences. It’s time we stopped and considered the price humanity would have to pay if we had even a “limited” nuclear war – limited geographically or in time. Experts suggest that using even one percent of our nuclear weapons would have a severe impact on the world’s climate, leading to a nuclear winter and a global famine in which 2 billion people―a quarter of the world’s population―would be at risk of starvation. These are unacceptable costs. Are we really willing to pay them?

As we stand on the precipice of unprecedented horror and untold suffering, we have a choice to make: we can continue our self-destructive dive into the abyss or work assiduously as a community of nations to build a global system of collective security that will ensure global peace and security. Such a system should be grounded in collectively agreed-upon international rules which are enforced even-handedly against any nation that threatens the peace using an international standing force that acts at the behest of, and in service to, the international community.

Image source: Photo courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration / Nevada Site Office, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

by Lawrence Wittner | Jun 18, 2024 | Peace

International law―the recognized rules of behavior among nations based on customary practices and treaties, among them the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights―has been agreed upon by large and small nations alike. To implement this law, the nations of the world have established a UN Security Council (to maintain international peace and security) and a variety of international courts, including the UN’s International Court of Justice (which adjudicates disputes between nations and gives advisory opinions on international legal issues) and the International Criminal Court (which prosecutes individuals for crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression).

Yet nations continue to defy international law.

In the ongoing Gaza crisis, the Israeli government has failed to uphold international law by rebuffing the calls of international organizations to end its massive slaughter of Palestinian civilians. The U.S. government has facilitated this behavior by vetoing three UN Security Council resolutions calling for a ceasefire, while the Israeli government has ignored an International Court of Justice ruling that it should head off genocide in Gaza by ensuring sufficient humanitarian assistance to the Palestinian population. The Israeli government has also refused to honor an order by the International Court of Justice to halt its offensive in Rafah and denounced the International Criminal Court’s request for arrest warrants for its top officials.

Russia’s military assault upon Ukraine provides another example of flouting international law. Given the UN Charter’s prohibition of the “use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state,” when Russian military forces seized and annexed Crimea and commenced military operations to gobble up eastern Ukraine in early 2014, the issue came before the UN Security Council, where condemnation of Russia’s action was promptly vetoed by Russia. Similarly, in February 2022, when the Russian government commenced a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia again vetoed Security Council action. That March, the International Court of Justice, by an overwhelming vote, ordered Russia to halt its invasion of Ukraine—but, as usual, to no avail.

Unfortunately, these violations of international law are not unusual for, over many decades, numerous nations have ignored the recognized rules of international conduct.

What is lacking is not international law but, rather, its consistent and universal enforcement. For decades, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the United States, Russia, China, Britain, and France) have repeatedly used their veto power in that entity to block UN action to maintain international peace and security. Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of the world’s nations do not accept the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, while more than a third of the world’s nations (including some of the largest, such as Russia, the United States, China, and India) have resisted becoming parties to the International Criminal Court. Indeed, responding to the International Criminal Court’s request for arrest warrants for Israeli officials, the U.S. House of Representatives promptly passed legislation to sanction that international organization.

Despite such obstacles, these international organizations have sometimes played very useful roles in resolving international disputes. The UN Security Council has dispatched numerous peacekeeping missions around the world―including 60 alone in the years since the dissolution of the Soviet Union―that have helped defuse crises in conflict-ridden regions.

For its part, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) paved the way for the Central American Peace Accords during the 1980s through its ruling in Nicaragua v United States, while its ruling in the Nuclear Tests case helped bring an end to nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific. In addition, the ICJ’s ruling in Chad v Libya resolved a territorial dispute between these two nations and ended their military conflict.

Although the International Criminal Court has only been in operation since 2002, it has thus far convicted ten individuals of heinous crimes, issued or requested warrants for the arrest of prominent figures charged with war crimes (including Vladimir Putin, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the leaders of Hamas), and conducted or begun investigations of yet other notorious individuals.

But, of course, as demonstrated by the persistence of wars of aggression and massive violations of human rights, enforcing international law remains a major problem in the contemporary world.

Therefore, if the world is to move beyond national impunity―if it is finally to scrap the long and disgraceful tradition among nations of might makes right―it is necessary to empower the world’s major international organizations to enforce the international law that nations have agreed to respect.

This strengthening of global governance is certainly possible.

Although provisions in the UN Charter make outright abolition of the UN Security Council veto very difficult, other means are available for reducing the veto’s baneful effects. In many cases ―including those of the Ukraine and Gaza conflicts―simply invoking Article 27(3) of the UN Charter would be sufficient, for it states that a party to a dispute before the Security Council shall abstain from voting in connection with that dispute. Furthermore, 124 UN nations have already endorsed a proposal for renunciation of the veto when taking action against genocide, crimes against humanity, and mass atrocities. Moreover, the UN General Assembly has occasionally employed “Uniting for Peace” resolutions to take action when the Security Council has failed to do so.

Improving the effectiveness of the international judicial system has also generated attention in recent years. The LAW Not War campaign, championed by organizations dedicated to improving global governance, advocates strengthening the International Court of Justice, principally by increasing the number of nations accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court. Similarly, the Coalition for the International Criminal Court, representing numerous organizations, calls on all nations to ratify the Court’s founding statute and, thereby, “expand the Court’s reach and reduce the impunity gap.”

National impunity is not inevitable, at least if people and governments of the world are willing to take the necessary actions. Are they? Or will they continue talking of a “rules-based international order” while they avoid enforcing the rules?

Image source: International Court of Justice; originally uploaded by Yeu Ninje at en.wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

by Lawrence Wittner | May 2, 2024 | Disarmament

What will it take to end the nuclear nightmare that has gripped the world since the atomic bombings of 1945?

For a time, that nightmare seemed to have abated for, in response to massive popular resistance to the prospect of nuclear war, governments turned to signing nuclear arms control and disarmament agreements. Even previously hawkish government officials proclaimed that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”

In recent decades, however, nuclear-armed nations have scrapped nuclear arms control and disarmament treaties, begun the massive upgrading and expansion of their nuclear arsenals, and publicly threatened other nations with nuclear war. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which has assessed the nuclear situation since 1946, has turned the hands of its “Doomsday Clock” to 90 seconds to midnight, the most dangerous setting in its history.

Why has this renewed flirtation with nuclear Armageddon occurred?

One reason for the nuclear revival is that, in a world of independent, feuding nations, governments turn naturally to arming themselves with the most powerful weapons available and, sometimes, to war. Thus, with the decline of the worldwide nuclear disarmament campaign of the 1980s, governments have felt freer to engage their natural proclivities.

A second, less apparent reason is that the movement and government officials alike have ceased thinking systemically. Or, to put it another way, they have forgotten that the motor force behind nations’ reliance upon nuclear weapons is international anarchy.

In the late 1940s, during the first wave of the popular campaign against the Bomb, the movement recognized that nuclear weapons grew out of the centuries-old conflicts among nations. Consequently, millions of people across the globe, shocked by the atomic bombings of 1945, rallied around the slogan “One World or None.”

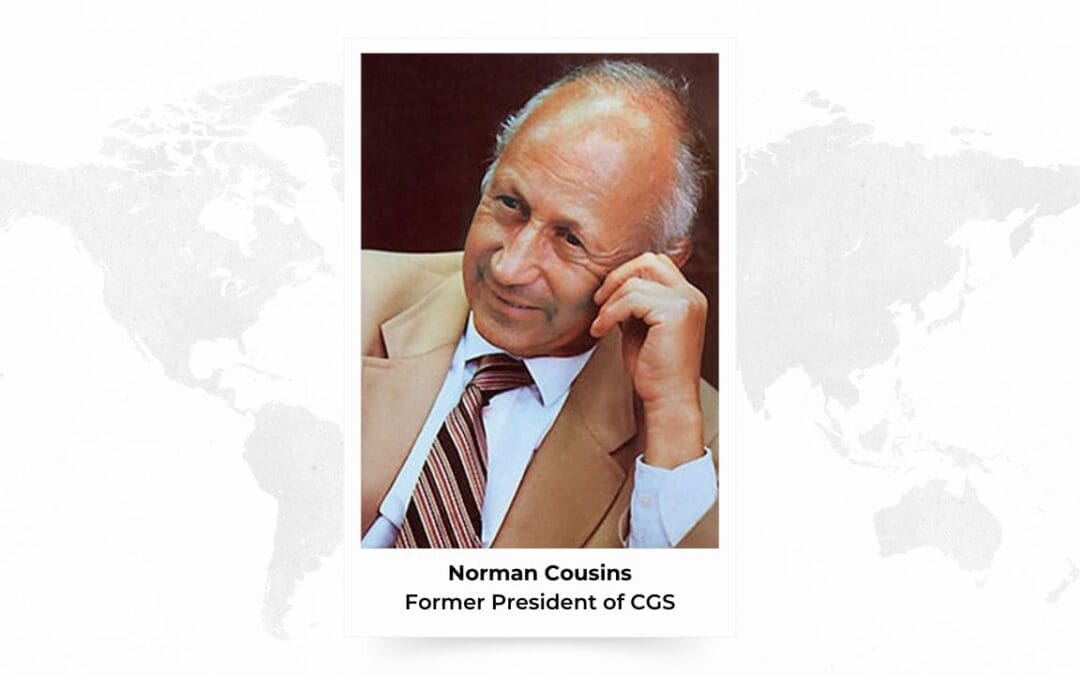

In the United States, Norman Cousins, the young editor of the Saturday Review of Literature, sat down on the evening of the destruction of Hiroshima and wrote a lengthy editorial, “Modern Man Is Obsolete.” The “need for world government was clear long before August 6, 1945,” he observed, but the atomic bombing “raised the need to such dimensions that it can no longer be ignored.” Becoming a key writer, speaker, and fundraiser for the cause, Cousins turned the editorial into a book that went through 14 editions, appeared in seven languages, and had a circulation in the United States of seven million copies. He also became a leader in a new, rapidly-growing organization, United World Federalists, which by mid-1949 had 720 chapters and nearly 50,000 members.

Around the world, the atomic bombing provoked a similar response. Atomic scientists, horrified by the prospect of worldwide destruction, published a book titled One World or None, organized international antinuclear campaigns among scientists, and emphasized the need for a global solution to the nuclear problem. Many, like Albert Einstein, became prominent world federalists or, like Robert Oppenheimer, viewed international control of nuclear weapons as a task that necessitated overriding national sovereignty.

The antinuclear uprising of the late 1940s had some impact upon public policy. Major governments, previously enthusiastic about nuclear weapons, grew ambivalent about their development and use. Indeed, the appearance of the Baruch Plan, the world’s first serious nuclear disarmament proposal, owed much to the postwar agitation.

Nevertheless, as the Cold War emerged, the officials of the great powers rejected the new way of thinking about relations among nations championed by Einstein and other activists. Instead of restructuring international relations to cope with the unprecedented peril of the Bomb, they incorporated the Bomb into the traditional framework of international conflict. The result was a nuclear arms race and a growing sense that agitation for transforming the international order was, at best, naïve, or, at worst, subversive.

These narrowed political horizons meant that, when the antinuclear movement revived in the late 1950s, it championed more limited objectives, beginning with a call for ending nuclear testing. And this goal proved attainable, at least in part, because halting atmospheric nuclear testing did not seriously hinder the great powers, which could move tests underground and, thereby, upgrade their nuclear arsenals. The result was the passage of the world’s first nuclear arms control agreement, the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963.

Admittedly, ban-the-bomb movements also sprang up in numerous countries. But, although they were sometimes headed by long-time proponents of world government, including Norman Cousins (chair of America’s National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy) and Bertrand Russell (president of Britain’s Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament), they, too, focused on weapons rather than on reforming the international system. The result was a welcome surge of nuclear arms control treaties in the late 1960s and early 1970s that quieted the fears of activists and led to the movement’s decline.

When the Cold War revived in the late 1970s and early 1980s, so did an outraged antinuclear campaign. Indeed, this third wave of the nuclear disarmament movement proved the largest and most successful yet, securing substantial decreases in nuclear arsenals and significantly reducing the danger of nuclear war.

Of all the major actors of that era, though, only Mikhail Gorbachev seemed ready to move beyond weapons cutbacks to advocate the development of a new international security system. But with the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Gorbachev was swept from power. And, in recent decades, rising international tensions have swept away the antinuclear campaign’s hard-won gains, as well.

Those gains, though evanescent, were important, for they helped the world to avoid nuclear war while giving it time to press on toward a nuclear weapons-free future.

But this history also suggests that, in the struggle for survival in the nuclear age, confronting the continued anarchy of nations cannot be avoided. Indeed, given the severity of our current international crises and the escalating nuclear menace that they generate, the time has come to revisit the forgotten issue of strengthening the international security system.