by Sovaida Maani Ewing | Feb 20, 2026 | Disarmament, UN Reform

In 2011, the New START Treaty, which had been signed by the United States and Russia the previous year, came into effect. The Treaty aimed to restrict the number of nuclear warheads the two nations could deploy. It also provided for a verification system to ensure that both sides were complying with the Treaty rules by providing for on-site inspections of their respective nuclear sites. This month, the Treaty expired.

With the end of the New START Treaty, the nuclear arms race is likely to heat up again. This time, it will be more complicated and dangerous than it was during the Cold War, given that another big power China—has already vigorously entered the race. She has been determinedly and steadily growing her nuclear arsenal, particularly since 2012. Consequently, one of America’s great fears is that, instead of having to defend herself against Russia alone, she might have to face both China and Russia, especially if they choose to join forces.

The problem is that if, in anticipation of such danger, America starts to deploy more nuclear weapons, Russia will follow suit and China will likely step up her efforts even further, setting off a domino effect: China’s neighbor India, with which it has long had slow-burning border conflicts, is also likely to become nervous about a steady increase in nuclear deployments and so follow suit. Such a move would most probably trigger Pakistan to react in kind, to protect herself against her nuclear neighbor, India. And so the dominoes fall.

The problem will be compounded: those countries in Europe and Asia which have been relying on the American nuclear umbrella to shield them against aggression may well conclude that in an increasingly nuclear insecure world, the only effective way to bolster their own protection is to seek their own nuclear capabilities.

As smaller nations seek to acquire nuclear arms, their larger and more powerful neighbors may feel increasingly threatened and evince more aggressive tendencies to quash such nascent nuclear ambitions, leading to a world that is increasingly unstable and insecure.

We must act swiftly and decisively to arrest this dangerous descent into nuclear chaos, which can only result in a nuclear war that, however limited in geographic scope or duration, will have a devastating impact on the entire planet. The most effective path is for nations to create a world parliament that is democratically elected by the people of each country and therefore truly represents the interests of the collective whole. This parliament should be granted the authority to pass international laws on the basis of some sort of majority vote, that are binding on all the nations of the world. No nation can be allowed to opt out for any reason. The law must apply equally to all nations, great or small, powerful or weak. A suitable enforcement mechanism must also be devised and agreed upon, so that nations are suitably deterred from any temptation to flout the Parliament’s international law with impunity.

The time has come for humanity to take this next, inevitable step in its collective evolution. It is an idea whose time has come!

by Lawrence Wittner | Feb 17, 2026 | Disarmament

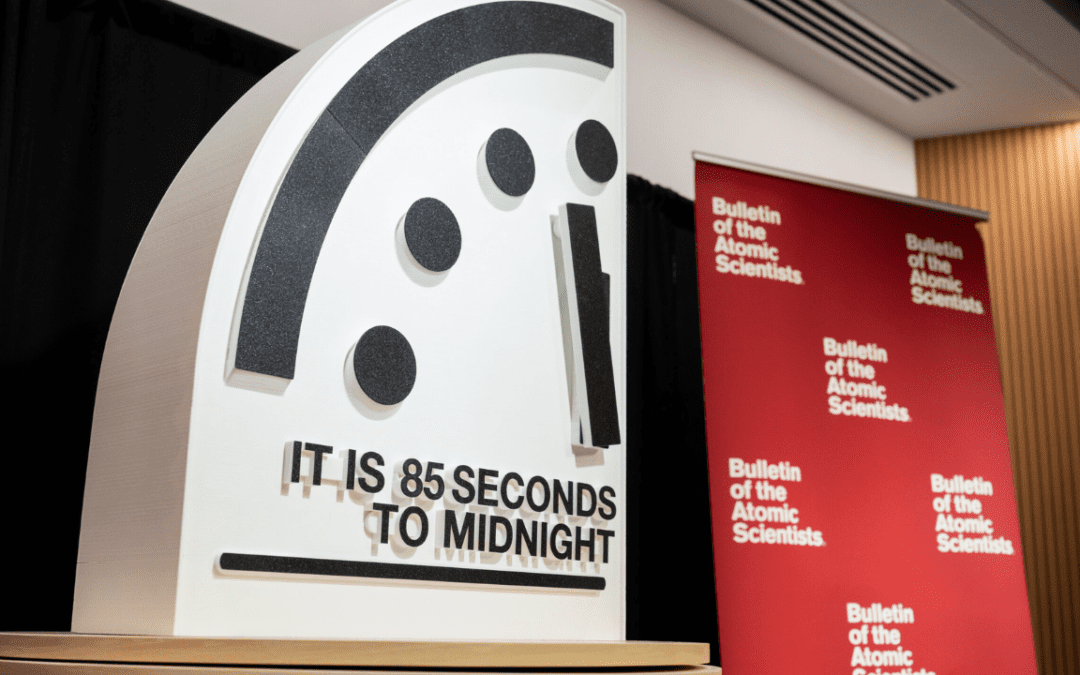

On January 27, 2026, the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved the hands of their famous “Doomsday Clock” to 85 seconds to midnight―the closest setting, since the appearance of the clock in 1946, to nuclear annihilation.

This grim appraisal has impressive evidence to support it.

The New Start Treaty, the last of the major nuclear arms control and disarmament treaties between the United States and Russia, expired on February 5, without any serious attempt to replace it. New Start’s demise enables both nations, which possess about 86 percent of the world’s 12,321 nuclear weapons, to move beyond the strict limits set by the treaty on the number of their strategic nuclear weapons (the most powerful, most devastating kind), thus enhancing the ability of their governments to reduce the world to a charred wasteland.

Actually, a nuclear arms race has been gathering steam for years, as nearly all the governments of the nine nuclear powers (which, in addition to Russia and the United States, include China, Britain, France, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea) scramble to upgrade existing weapons systems and add newer versions. China’s nuclear arsenal is the fastest-growing among them. “The era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world . . . is coming to an end,” observed Hans Kristensen, a highly regarded expert on nuclear armament and disarmament. “Instead, we see a clear trend of growing nuclear arsenals, sharpened nuclear rhetoric, and the abandonment of arms control agreements.”

The U.S. government is currently immersed in a $1.7 trillion nuclear “modernization” program that President Donald Trump has championed and repeatedly lauded. As early as February 2018, he boasted that his administration was “creating a brand-new nuclear force. We’re gonna be so far ahead of everybody else in nuclear like you’ve never seen before.” In late October 2025, to facilitate the U.S. nuclear buildup, Trump ordered the Pentagon to prepare to resume U.S. nuclear weapons testing, which had ceased 33 years before. In line with the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty of 1996, signed by 187 nations (including the United States), no nuclear power (other than the rogue nation of North Korea) has conducted explosive nuclear testing in over 25 years.

Another sign of the escalating nuclear danger is the revival of implicit and explicit threats to initiate nuclear war. Such threats, which declined with the end of the Cold War, have resurfaced in recent years. When angered by the policies of other nations, Donald Trump, Kim Jong Un, and Vladimir Putin have repeatedly and publicly threatened them with nuclear destruction. According to the U.S. government’s Voice of America, the Russian government, in the context of its invasion of Ukraine, issued 135 nuclear threats between February 2022 and December 17, 2024. Although some national security experts have discounted most Russian threats as manipulative rather than serious, in November 2022, Chinese leader Xi Jinping thought the matter serious enough to publicly chide his professed ally, Putin, for threatening to resort to nuclear arms in Ukraine.

Underlying this drift toward nuclear war are the growing conflicts among nations―conflicts that have significantly weakened international cooperation and the United Nations. As the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists put it, rather than heed past warnings of catastrophe, “Russia, China, the United States, and other major countries have instead become increasingly aggressive, adversarial, and nationalistic.” Consequently, “hard-won global understandings are collapsing, accelerating a winner-takes-all great power competition and undermining the international cooperation critical to reducing the risks of nuclear war.”

But this is not necessarily the end of the story―or of the world.

After all, much the same situation existed in the second half of the twentieth century, when conflicts among the great powers fueled a dangerous nuclear arms race that, at numerous junctures, threatened to spiral into full-scale nuclear war. And, in response, a massive grassroots campaign emerged to save the world from nuclear annihilation. Although that campaign did not succeed in banning the bomb, it did manage to curb the nuclear arms race, reduce the number of nuclear weapons by more than 80 percent, and prevent a much-feared nuclear catastrophe.

Furthermore, in the early twenty-first century, there have been new and important developments. The worldwide remnants of the nuclear disarmament movement regrouped as the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons and, joined by farsighted officials in smaller, non-nuclear nations, drew upon the United Nations to sponsor a series of antinuclear conferences. In 2017, by a vote of 122 to 1 (with 1 abstention), delegates at one of these UN conferences adopted the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). Although all nine nuclear powers strongly opposed the TPNW―which banned the use, threatened use, development, manufacture, acquisition, possession, stockpiling, stationing, and installation of nuclear weapons―the treaty secured sufficient national backing to enter into force in January 2021. Thus far, it has been signed by 99 countries―a majority of the world’s nations.

In addition to the efficacy of public pressure for nuclear disarmament and the existence of a treaty banning nuclear weapons, at least one other factor points the way toward a non-nuclear future: the self-defeating nature—indeed, the insanity―of nuclear war. With even a single nuclear bomb capable of killing millions of people and leaving the desperate survivors crawling painfully through a burnt-out, radioactive hell, even a nuclear “victory” is a defeat. In the aftermath of a nuclear war, as Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev is believed to have said, “the survivors would envy the dead.” It’s a lesson that most people around the world have learned, although not perhaps the lunatics.

Lunatics, of course, exist, and some of them, unfortunately, govern modern nations and ignore international law.

Even so, although we are on the road to nuclear war, there is still time to take a deep breath, think about where we are going, and turn around.

by Lawrence Wittner | Oct 30, 2025 | Disarmament

Early this year, legislators in the U.S. House of Representatives and in the U.S. Senate introduced resolutions that call upon the U.S. government to lead a global effort to halt and reverse the nuclear arms race. Co-sponsored by 36 members of the House and 5 members of the Senate, H. Res. 317 and S. Res. 323 urge the U.S. government to pursue nuclear disarmament, renounce the first use of nuclear weapons, end sole presidential authority to launch them, cancel plans for new, enhanced nuclear weapons and delivery systems, maintain the current moratorium on nuclear testing explosions, and provide a just economic transition for impacted communities.

The context for these antinuclear measures is an escalating nuclear arms race that is rapidly spiraling out of control. In recent years, Russia and the United States, which together possess 87 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons, have scrapped nearly all their nuclear arms control agreements. The only exception is the New Start Treaty, which is scheduled to expire in February 2026. Meanwhile, all nine nuclear powers (Russia, United States, Britain, France, China, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea) have committed themselves to dramatically upgrading their nuclear arsenals. The U.S. government, for example, at the enormous cost of $1.7 trillion, is currently engaged in revamping its entire nuclear weapons complex and building an array of new, more devastating nuclear weapons.

This worldwide nuclear weapons buildup has been accompanied by a revival of public threats by the leaders of nuclear-armed nations to initiate nuclear war―threats that have been issued, repeatedly, by Donald Trump, Kim Jong Un, and Vladimir Putin. Not surprisingly, the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists currently stands at 89 seconds to midnight, the most dangerous setting in its history.

The House and Senate resolutions seeking to halt and reverse this race toward catastrophe are primarily the product of the Back from the Brink campaign. Founded in 2017 by the leaders of two U.S. national organizations, Physicians for Social Responsibility and the Union of Concerned Scientists, Back from the Brink has emerged as an impressive coalition of organizations, individuals, and public officials working together to create a world free of nuclear weapons.

At this point, the Back from the Brink campaign has secured the endorsement of a significant number of additional national organizations, including peace and disarmament groups like the American Friends Service Committee, the Federation of American Scientists, Pax Christi USA, Peace Action, and Veterans for Peace, religious organizations like the Episcopal Church, the Presbyterian Church, the Unitarian Universalist Association, and the United Church of Christ, environmental groups like 350.org, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and the Sierra Club, political activist groups like the Hip Hop Caucus and Indivisible, and governmental organizations like the United States Conference of Mayors.

In addition, the campaign has attracted the support of hundreds of local peace, academic, civic, environmental, health, policy, religious, and other organizations, as well as endorsements from 78 municipalities and counties, 8 state legislative bodies, 488 municipal and state officials, and 53 members of Congress.

Despite this array of support, Back from the Brink’s immediate prospects are not good. Its antinuclear resolutions, now awaiting action by the Republican-controlled House and Senate, seem unlikely to pass, as not a single Republican legislator has signed on as a co-sponsor of them thus far. Nor is it likely that President Donald Trump, who seems enamored with U.S. military “strength,” will champion halting, much less reversing, the nuclear arms race.

Longer term, however, the prospects are brighter. Unlike the Republican Party of recent decades, the Democratic Party has championed a variety of nuclear arms control and disarmament measures. Thus, if the Democrats do well in the 2026 midterm elections and, thereby, retake control of the House and the Senate, there is a reasonable chance that they will pass Back from the Brink’s antinuclear resolutions. Also, if the Democrats hold on to Congress and win the presidency in 2028, it’s quite possible that nuclear arms control and disarmament will appear once again on the U.S. government’s public policy agenda.

Of course, even if there are public policy advances along these lines, as there have been in the past, it will not end the immense danger of worldwide nuclear annihilation―a danger that emerged with startling clarity in 1945 with the advent and use of nuclear weapons to obliterate two Japanese cities. Ultimately, a secure future for civilization will be attained only when these weapons of mass destruction are abolished.

Is that feasible?

It’s certainly a possibility. After all, when directly confronted with the issue of human survival, most people have displayed an appropriate concern for it by demanding an end to the nuclear menace. And that goal could be attained by seeing to it that all nations sign and ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. That landmark treaty, which was hammered out painstakingly at the United Nations in 2017 and which entered into force in 2021, has already been signed by 95 countries (a majority of the world’s nations) and ratified by 74 of them.

Admittedly, the nine nuclear powers, still clinging doggedly to their nuclear weapons, are not among them. But, if there were a mobilization of substantial public pressure and the development of international security guarantees enforced by a strengthened United Nations, the reluctance of these holdouts could be overcome and a nuclear weapons-free world established.

Meanwhile, to provide us with the time it will take to get to this state of affairs, we do need to focus on turning back from the brink of nuclear war.

by Lawrence Wittner | Aug 6, 2025 | Disarmament

Ever since the atomic bombings of Japanese cities in August 1945, the world has been living on borrowed time.

The indications, then and since, that the development of nuclear weapons did not bode well for human survival, were clear enough. The two small atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killed between 110,000 and 210,000 people and wounded many others, almost all of them civilians. In subsequent years, hundreds of thousands more people around the world lost their lives thanks to the radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing, while substantial numbers also died from the mining of uranium for the building of nuclear weapons.

Most startlingly, the construction of nuclear weapons armadas against the backdrop of thousands of years of international conflict portended human extinction. Amid the escalating nuclear terror, Einstein declared: “General annihilation beckons.”

Despite the enormity of the nuclear danger, major governments, in the decades after 1945, were too committed to traditional thinking about international relations to resist the temptation to build nuclear weapons to safeguard what they considered their national security. Whatever the dangers, they concluded, military power still counted in an anarchic world. Consequently, they plunged into a nuclear arms race and, on occasion, threatened one another with nuclear war. At times, they came perilously close to it―not only during the 1963 Cuban missile crisis, but during the October 1973 Arab-Israeli war and on numerous other occasions.

By contrast, much of the public found nuclear weapons and the prospect of nuclear war very unappealing. Appalled by the nuclear menace, they rallied behind organizations like the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy in the United States, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in Britain, and comparable groups elsewhere that pressed for nuclear arms control and disarmament measures. This popular uprising secured its first clear triumph when, in the fall of 1958, the governments of the United States, the Soviet Union, and Britain agreed to halt nuclear weapons testing as they negotiated a test ban treaty. As the movement crested, it played an important role in securing the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963 and a cascade of nuclear arms control measures that followed.

Even when U.S. and Soviet officials revived the nuclear arms race in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a massive public uprising halted and reversed the situation, leading to the advent of major nuclear disarmament measures. As a result, the number of nuclear weapons in the world’s arsenals plummeted from about 70,000 to about 12,240 between 1986 and 2025. At a special meeting of the UN Security Council in 2009, the leaders of the major nuclear powers called for the building of a nuclear weapons-free world.

In recent decades, however, the dwindling of the popular movement and the heightening of international conflict have led to a revival of the nuclear arms race, now well underway. As three nuclear experts from the Federation of American Scientists reported this June: “Every nuclear country is improving its weapons systems, while some are growing their arsenals. Others are doing both.” The new nuclear weaponry currently being tested includes “cruise missiles that can fly for days before hitting their targets; underwater unmanned nuclear torpedoes; fast-flying maneuverable glide vehicles that can evade defenses; and nuclear weapons in space that can attack satellites or targets on Earth without warning.” The financial costs of the nuclear buildup by the nine nuclear powers (the United States, Russia, China, Britain, France, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea) will be immense. The U.S. government will reportedly spend over $1.7 trillion on its nuclear “modernization.”

To facilitate these nuclear war preparations, the major nuclear powers have withdrawn from key nuclear arms control and disarmament treaties. The New START Treaty, the last of the major U.S.-Russian nuclear agreements, terminates in February 2026.

Furthermore, over the past decade, the governments of North Korea, the United States, and Russia have issued public threats of nuclear war. In line with its threats, the Russian government announced in late 2024 that it had lowered its threshold for using nuclear weapons.

In response to these developments, the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has been set at 89 seconds to midnight, the most dangerous level in its 79-year history.

As the record of the years since 1945 indicates, the catastrophe of nuclear war can be averted. To accomplish this, however, a revival of public pressure for nuclear disarmament is essential, for otherwise governments easily slip into the traditional trap of enhancing military “strength” to cope with a conflict-ridden world―a practice that, in the nuclear age, is a recipe for disaster.

This public pressure could begin, as the Nuclear Freeze movement of the 1980s did, with a call to halt the nuclear arms race, and could continue with the demand for specific nuclear arms control and disarmament measures.

But, simultaneously, the movement needs to champion the strengthening of global institutions―institutions that can provide greater international security than presently exists. The existence of these strengthened institutions―for example, a stronger United Nations―would help resolve the violent conflicts among nations that spawn arms races and would undermine lingering public and official beliefs that nuclear weapons are essential to safeguard national security.

Once the world is back on track toward nuclear disarmament, the movement could focus on its campaign for the signing and ratification of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. This treaty, providing the framework for a nuclear weapons-free world, was adopted in 2017 by most of the world’s nations and went into force in 2021. Thus far, it has been signed by 94 nations and ratified by 73 of them.

Given recent international circumstances, none of the nuclear powers has signed it. But with widespread popular pressure and enhanced international security, they could ultimately be brought on board.

They certainly should be, for human survival depends upon ending the nuclear terror.

by Lawrence Wittner | May 22, 2025 | Disarmament

Although the statement that “power grows out of the barrel of a gun” was made by Chinese communist leader Mao Zedong, it’s an idea that, in one form or another, has motivated a great many people, from the members of teenage street gangs to the statesmen of major nations.

The rising spiral of world military spending provides a striking example of how highly national governments value armed forces. In 2024, the nations of the world spent a record $2.72 trillion on expanding their vast military strength, an increase of 9.4 percent from the previous year. It was the tenth year of consecutive spending increases and the steepest annual rise in military expenditures since the end of the Cold War.

This enormous investment in military might is hardly a new phenomenon. Over the broad sweep of human history, nations have armed themselves―often at great cost―in preparation for war. And an endless stream of wars has followed, resulting in the deaths of perhaps a billion people, most of them civilians. During the 20th century alone, war’s human death toll numbered 231 million.

Even larger numbers of people have been injured in these wars, including many who have been crippled, blinded, hideously burned, or driven mad. In fact, the number of people who have been wounded in war is at least twice the number killed and has sometimes soared to 13 times that number.

War has produced other calamities, as well. The Russian military invasion of Ukraine, for example, has led to the displacement of a third of that nation’s population. In addition, war has caused immense material damage. Entire cities and, sometimes, nations have been reduced to rubble, while even victorious countries sometimes found themselves bankrupted by war’s immense financial costs. Often, wars have brought long-lasting environmental damage, leading to birth defects and other severe health consequences, as the people of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Vietnam, and the Middle East can attest.

Even when national military forces were not engaged in waging foreign wars, they often produced very undesirable results. The annals of history are filled with incidents of military officers who have used their armies to stage coups and establish brutal dictatorships in their own countries. Furthermore, the possession of military might has often emboldened national leaders to intimidate weaker nations or to embark upon imperial conquest. It’s no accident that nations with the most powerful military forces (“the great powers”) are particularly prone to war-making.

Moreover, prioritizing the military has deprived other sectors of society of substantial resources. Money that could have gone into programs for education, healthcare, food stamps, and other social programs has been channeled instead into unprecedented levels of spending to enhance military might.

It’s a sorry record for what passes as world civilization―one that will surely grow far worse, or perhaps terminate human existence, with the onset of a nuclear war.

Of course, advocates of military power argue that, in a dangerous world, there is a necessity for deterring a military attack upon their nations. And that is surely a valid concern.

But does military might really meet the need for national security? In addition to the problems spawned by massive military forces, it’s not clear that these forces are doing a good job of deterring foreign attack. After all, every year government officials say that their countries are facing greater danger than ever before. And they are right about this. The world is becoming a more dangerous place. A major reason is that the military might sought by one nation for its national security is regarded by other nations as endangering their national security. The result is an arms race and, frequently, war.

Fortunately, though, there are alternatives to the endless process of military buildups and wars.

The most promising among them is the establishment of international security. This could be accomplished through the development of international treaties and the strengthening of international institutions.

Treaties, of course, can establish rules for international behavior by nations while, at the same time, resolving key problems among them (for example, the location of national boundaries) and setting policies that are of benefit to all (for example, reducing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere). Through arms control and disarmament agreements they can also address military dangers. For example, in place of the arms race, they could sponsor a peace race, in which each nation would reduce its military spending by 10 per cent per year. Or nations could sign and ratify (as many have already done) the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which would end the menace of nuclear annihilation.

International institutions can also play a significant role in reducing international conflict and, thus, the resort to military action. The United Nations, established in 1945, is tasked with maintaining international peace and security, while the International Court of Justice was established to settle legal disputes among nations and the International Criminal Court to investigate and, where justified, try individuals for genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of aggression.

Unfortunately, these international organizations are not fully able to accomplish their important tasks―largely because many nations prefer to rely upon their own military might and because some nations (particularly the United States, Russia, and Israel) are enraged that these organizations have criticized their conduct in world affairs. Even so, international organizations have enormous potential and, if strengthened, could play a vital role in creating a less violent world.

Rather than continuing to pour the wealth of nations into the failing system of national military power, how about bolstering these global instruments for attaining international security and peace?

by Lawrence Wittner | Apr 7, 2025 | Disarmament

Amid growing international chaos, it should come as no surprise that nuclear dangers are increasing.

The latest indication is a rising interest among U.S. allies in enhancing their nuclear weapons capability. For many decades, remarkably few of them had been willing to build nuclear weapons―a result of popular opposition to nuclear weapons and nuclear war, progress on nuclear arms control and disarmament, and a belief that they remained secure under the U.S. nuclear umbrella. But, as revealed by a recent article in London’s Financial Times, Donald Trump’s public scorn for NATO allies and embrace of Vladimir Putin have raised fears of U.S. unreliability, thereby tipping the balance toward developing an expanded nuclear weapons capability.

This growing interest in nuclear weapons is especially noticeable in Europe, where Trump’s berating of NATO and Putin’s threats of nuclear attack are particularly unsettling. Although Friedrich Merz, Germany’s chancellor-in-waiting, dismissed any notion of Germany developing its own nuclear weapons, he has stated that it must explore “whether nuclear sharing, or at least nuclear security from the U.K. and France, could also apply to us.” Furthermore, several German think tank experts have floated the idea of building the infrastructure that, if necessary, could produce German nuclear weapons.

In Poland, too, a nuclear weapons capacity has become increasingly appealing. Prime Minister Donald Tusk has recently raised the idea of pursuing nuclear weapons or, at least, seeking an agreement for sharing France’s nuclear arsenal. A board director of PGZ, Poland’s state-controlled military manufacturer, remarked: “There are suddenly a lot of words and different opinions about what to do, but they all show Poland believes in stronger nuclear deterrence against Russia.”

In South Korea, North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and its growing military relationship with Russia, combined with Trump’s unreliability, have contributed to growing support for the nation’s acquiring its own nuclear weapons. Although neither of the two major parties has announced this policy, Cho Tae-yul, the foreign minister, informed parliament that acquiring nuclear weapons was “not off the table,” for “we must prepare for all scenarios.”

Similarly, the idea of developing nuclear weapons is drawing increasing scrutiny in Japan. Sharing South Korea’s fear of a North Korean attack and Trump’s unreliability, Japanese leaders also worry about China’s growing assertiveness. If a North Korean or Chinese nuclear strike occurred, Japan would have only five minutes of warning time. Moreover, thanks to its nuclear power plants, Japan already holds enough plutonium to build several thousand nuclear bombs.

In addition, of course, a nuclear arms race is well underway among the nuclear weapons-producing nations: the United States, Russia, China, Britain, France, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea. All of them are either expanding their nuclear arsenals, building a new generation of nuclear weapons, or both. Most of the nuclear arms control and disarmament agreements of the past have been abandoned, while the remaining agreements are on life support. The New Start Treaty between Russia and the United States, the two nations possessing almost 90% of the world’s 12,331 nuclear weapons, is scheduled to expire in February 2026, and there are no negotiations underway to replace it. Meanwhile, in recent years, the top officials of three nuclear-armed nations―Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, and Kim Jong Un―have issued numerous statements threatening nuclear war.

Against this backdrop, this January the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists reset their “Doomsday Clock,” established in 1946, at 89 seconds to midnight, the closest ever to human extinction. The following month, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres, deploring the unraveling of international security arrangements, warned that nuclear weapons provided a “one-way road to annihilation.”

These escalating nuclear dangers suggest that, if nuclear weapons, whether possessed by an alliance or by individual nations, are unable to safeguard humanity from total destruction, then a different approach to survival in the nuclear age is needed: one grounded in international security.

With this in mind, the official representatives of most of the world’s nations, gathering in 2017 under U.N. auspices, met and crafted the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Endorsed by a vote of 122 to 1 (with one abstention), it banned the use, threatened use, development, manufacture, acquisition, possession, stockpiling, stationing, and installation of nuclear weapons. The treaty entered into force in January 2021, and has been signed, thus far, by 94 nations. Opinion polls and declarations by hundreds of cities in a variety of nations indicate that it has substantial public support.

Although the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons provides a useful framework for creating a nuclear weapons-free world, it has not, as yet, rolled back the nuclear menace. The reason is that its provisions are only binding on the nations that have signed it. And the nine nuclear weapons-producing nations, joined by the nations under their nuclear umbrella, refuse to do so―at least so far. Convinced that, in a world of independent and often hostile nations, their security rests upon possession of nuclear weapons, they remain unwilling to abolish them.

Even so, their resistance to the treaty might be overcome by a further step toward international security: the strengthening of international organizations. At present, the United Nations lacks the power to effectively enforce its primary mission of maintaining international peace and security. But that power could be expanded by providing the global organization with an independent source of income, restricting the role of the veto in the Security Council, and expanding the role of the General Assembly. International security would also be enhanced by increasing the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice and of the International Criminal Court.

Both Citizens for Global Solutions (CGS) and the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Global Policy have teamed up with many other concerned civil society organizations to champion “Common Security” as an alternative to nuclear deterrence. In a joint statement to the 2023 Preparatory Committee for the 11th Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference, they argued that the primary reason a significant number of nations continued to rely on nuclear weapons was “because nuclear deterrence is perceived by them as providing security.” But adopting a Common Security approach―one that took into account not only one’s own security needs, but the security needs of other nations, including adversaries―could provide a sound basis for abandoning nuclear weapons, they maintained. During the meeting in late April and early May of the 2025 Preparatory Committee for the NPT Review Conference, CGS will be holding a side event on “Common Security and Nuclear Deterrence in a Turbulent World,” as well as another on “The International Court of Justice and the Climate-Nuclear Nexus.”

Strengthening international security might seem impractical at this time of overheated nationalist claims and the global chaos they produce. Even so, times of crisis sometimes produce historic breakthroughs, and the prospect of nuclear annihilation might have that effect.