by Lawrence Wittner | Jun 18, 2024 | Peace

International law―the recognized rules of behavior among nations based on customary practices and treaties, among them the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights―has been agreed upon by large and small nations alike. To implement this law, the nations of the world have established a UN Security Council (to maintain international peace and security) and a variety of international courts, including the UN’s International Court of Justice (which adjudicates disputes between nations and gives advisory opinions on international legal issues) and the International Criminal Court (which prosecutes individuals for crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression).

Yet nations continue to defy international law.

In the ongoing Gaza crisis, the Israeli government has failed to uphold international law by rebuffing the calls of international organizations to end its massive slaughter of Palestinian civilians. The U.S. government has facilitated this behavior by vetoing three UN Security Council resolutions calling for a ceasefire, while the Israeli government has ignored an International Court of Justice ruling that it should head off genocide in Gaza by ensuring sufficient humanitarian assistance to the Palestinian population. The Israeli government has also refused to honor an order by the International Court of Justice to halt its offensive in Rafah and denounced the International Criminal Court’s request for arrest warrants for its top officials.

Russia’s military assault upon Ukraine provides another example of flouting international law. Given the UN Charter’s prohibition of the “use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state,” when Russian military forces seized and annexed Crimea and commenced military operations to gobble up eastern Ukraine in early 2014, the issue came before the UN Security Council, where condemnation of Russia’s action was promptly vetoed by Russia. Similarly, in February 2022, when the Russian government commenced a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia again vetoed Security Council action. That March, the International Court of Justice, by an overwhelming vote, ordered Russia to halt its invasion of Ukraine—but, as usual, to no avail.

Unfortunately, these violations of international law are not unusual for, over many decades, numerous nations have ignored the recognized rules of international conduct.

What is lacking is not international law but, rather, its consistent and universal enforcement. For decades, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the United States, Russia, China, Britain, and France) have repeatedly used their veto power in that entity to block UN action to maintain international peace and security. Furthermore, nearly two-thirds of the world’s nations do not accept the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, while more than a third of the world’s nations (including some of the largest, such as Russia, the United States, China, and India) have resisted becoming parties to the International Criminal Court. Indeed, responding to the International Criminal Court’s request for arrest warrants for Israeli officials, the U.S. House of Representatives promptly passed legislation to sanction that international organization.

Despite such obstacles, these international organizations have sometimes played very useful roles in resolving international disputes. The UN Security Council has dispatched numerous peacekeeping missions around the world―including 60 alone in the years since the dissolution of the Soviet Union―that have helped defuse crises in conflict-ridden regions.

For its part, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) paved the way for the Central American Peace Accords during the 1980s through its ruling in Nicaragua v United States, while its ruling in the Nuclear Tests case helped bring an end to nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific. In addition, the ICJ’s ruling in Chad v Libya resolved a territorial dispute between these two nations and ended their military conflict.

Although the International Criminal Court has only been in operation since 2002, it has thus far convicted ten individuals of heinous crimes, issued or requested warrants for the arrest of prominent figures charged with war crimes (including Vladimir Putin, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the leaders of Hamas), and conducted or begun investigations of yet other notorious individuals.

But, of course, as demonstrated by the persistence of wars of aggression and massive violations of human rights, enforcing international law remains a major problem in the contemporary world.

Therefore, if the world is to move beyond national impunity―if it is finally to scrap the long and disgraceful tradition among nations of might makes right―it is necessary to empower the world’s major international organizations to enforce the international law that nations have agreed to respect.

This strengthening of global governance is certainly possible.

Although provisions in the UN Charter make outright abolition of the UN Security Council veto very difficult, other means are available for reducing the veto’s baneful effects. In many cases ―including those of the Ukraine and Gaza conflicts―simply invoking Article 27(3) of the UN Charter would be sufficient, for it states that a party to a dispute before the Security Council shall abstain from voting in connection with that dispute. Furthermore, 124 UN nations have already endorsed a proposal for renunciation of the veto when taking action against genocide, crimes against humanity, and mass atrocities. Moreover, the UN General Assembly has occasionally employed “Uniting for Peace” resolutions to take action when the Security Council has failed to do so.

Improving the effectiveness of the international judicial system has also generated attention in recent years. The LAW Not War campaign, championed by organizations dedicated to improving global governance, advocates strengthening the International Court of Justice, principally by increasing the number of nations accepting the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court. Similarly, the Coalition for the International Criminal Court, representing numerous organizations, calls on all nations to ratify the Court’s founding statute and, thereby, “expand the Court’s reach and reduce the impunity gap.”

National impunity is not inevitable, at least if people and governments of the world are willing to take the necessary actions. Are they? Or will they continue talking of a “rules-based international order” while they avoid enforcing the rules?

Image source: International Court of Justice; originally uploaded by Yeu Ninje at en.wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

by Lawrence Wittner | May 2, 2024 | Disarmament

What will it take to end the nuclear nightmare that has gripped the world since the atomic bombings of 1945?

For a time, that nightmare seemed to have abated for, in response to massive popular resistance to the prospect of nuclear war, governments turned to signing nuclear arms control and disarmament agreements. Even previously hawkish government officials proclaimed that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.”

In recent decades, however, nuclear-armed nations have scrapped nuclear arms control and disarmament treaties, begun the massive upgrading and expansion of their nuclear arsenals, and publicly threatened other nations with nuclear war. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which has assessed the nuclear situation since 1946, has turned the hands of its “Doomsday Clock” to 90 seconds to midnight, the most dangerous setting in its history.

Why has this renewed flirtation with nuclear Armageddon occurred?

One reason for the nuclear revival is that, in a world of independent, feuding nations, governments turn naturally to arming themselves with the most powerful weapons available and, sometimes, to war. Thus, with the decline of the worldwide nuclear disarmament campaign of the 1980s, governments have felt freer to engage their natural proclivities.

A second, less apparent reason is that the movement and government officials alike have ceased thinking systemically. Or, to put it another way, they have forgotten that the motor force behind nations’ reliance upon nuclear weapons is international anarchy.

In the late 1940s, during the first wave of the popular campaign against the Bomb, the movement recognized that nuclear weapons grew out of the centuries-old conflicts among nations. Consequently, millions of people across the globe, shocked by the atomic bombings of 1945, rallied around the slogan “One World or None.”

In the United States, Norman Cousins, the young editor of the Saturday Review of Literature, sat down on the evening of the destruction of Hiroshima and wrote a lengthy editorial, “Modern Man Is Obsolete.” The “need for world government was clear long before August 6, 1945,” he observed, but the atomic bombing “raised the need to such dimensions that it can no longer be ignored.” Becoming a key writer, speaker, and fundraiser for the cause, Cousins turned the editorial into a book that went through 14 editions, appeared in seven languages, and had a circulation in the United States of seven million copies. He also became a leader in a new, rapidly-growing organization, United World Federalists, which by mid-1949 had 720 chapters and nearly 50,000 members.

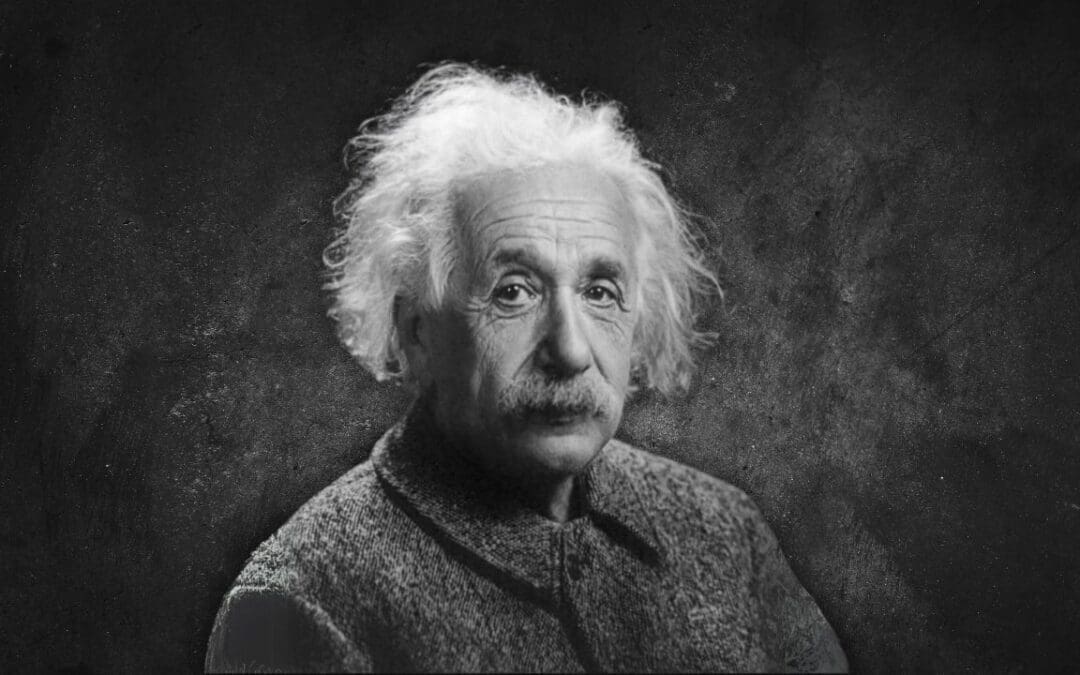

Around the world, the atomic bombing provoked a similar response. Atomic scientists, horrified by the prospect of worldwide destruction, published a book titled One World or None, organized international antinuclear campaigns among scientists, and emphasized the need for a global solution to the nuclear problem. Many, like Albert Einstein, became prominent world federalists or, like Robert Oppenheimer, viewed international control of nuclear weapons as a task that necessitated overriding national sovereignty.

The antinuclear uprising of the late 1940s had some impact upon public policy. Major governments, previously enthusiastic about nuclear weapons, grew ambivalent about their development and use. Indeed, the appearance of the Baruch Plan, the world’s first serious nuclear disarmament proposal, owed much to the postwar agitation.

Nevertheless, as the Cold War emerged, the officials of the great powers rejected the new way of thinking about relations among nations championed by Einstein and other activists. Instead of restructuring international relations to cope with the unprecedented peril of the Bomb, they incorporated the Bomb into the traditional framework of international conflict. The result was a nuclear arms race and a growing sense that agitation for transforming the international order was, at best, naïve, or, at worst, subversive.

These narrowed political horizons meant that, when the antinuclear movement revived in the late 1950s, it championed more limited objectives, beginning with a call for ending nuclear testing. And this goal proved attainable, at least in part, because halting atmospheric nuclear testing did not seriously hinder the great powers, which could move tests underground and, thereby, upgrade their nuclear arsenals. The result was the passage of the world’s first nuclear arms control agreement, the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963.

Admittedly, ban-the-bomb movements also sprang up in numerous countries. But, although they were sometimes headed by long-time proponents of world government, including Norman Cousins (chair of America’s National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy) and Bertrand Russell (president of Britain’s Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament), they, too, focused on weapons rather than on reforming the international system. The result was a welcome surge of nuclear arms control treaties in the late 1960s and early 1970s that quieted the fears of activists and led to the movement’s decline.

When the Cold War revived in the late 1970s and early 1980s, so did an outraged antinuclear campaign. Indeed, this third wave of the nuclear disarmament movement proved the largest and most successful yet, securing substantial decreases in nuclear arsenals and significantly reducing the danger of nuclear war.

Of all the major actors of that era, though, only Mikhail Gorbachev seemed ready to move beyond weapons cutbacks to advocate the development of a new international security system. But with the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Gorbachev was swept from power. And, in recent decades, rising international tensions have swept away the antinuclear campaign’s hard-won gains, as well.

Those gains, though evanescent, were important, for they helped the world to avoid nuclear war while giving it time to press on toward a nuclear weapons-free future.

But this history also suggests that, in the struggle for survival in the nuclear age, confronting the continued anarchy of nations cannot be avoided. Indeed, given the severity of our current international crises and the escalating nuclear menace that they generate, the time has come to revisit the forgotten issue of strengthening the international security system.

by Lawrence Wittner | Mar 2, 2024 | Disarmament

Although the popular new Netflix film, Einstein and the Bomb, purports to tell the story of the great physicist’s relationship to nuclear weapons, it ignores his vital role in rallying the world against nuclear catastrophe.

Aghast at the use of nuclear weapons in August 1945 to obliterate the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Einstein threw himself into efforts to prevent worldwide nuclear annihilation. In September, responding to a letter from Robert Hutchins, Chancellor of the University of Chicago, about nuclear weapons, Einstein contended that, “as long as nations demand unrestricted sovereignty, we shall undoubtedly be faced with still bigger wars, fought with bigger and technologically more advanced weapons.” Thus, “the most important task of intellectuals is to make this clear to the general public and to emphasize over and over again the need to establish a well-organized world government.” Four days later, he made the same point to an interviewer, insisting that “the only salvation for civilization and the human race lies in the creation of a world government, with security of nations founded upon law.”

Determined to prevent nuclear war, Einstein repeatedly hammered away at the need to replace international anarchy with a federation of nations operating under international law. In October 1945, together with other prominent Americans (among them Senator J. William Fulbright, Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, and novelist Thomas Mann), Einstein called for a “Federal Constitution of the World.” That November, he returned to this theme in an interview published in the Atlantic Monthly. “The release of atomic energy has not created a new problem,” he said. “It has merely made more urgent the necessity of solving an existing one. . . . As long as there are sovereign nations possessing great power, war is inevitable.” And war, sooner or later, would become nuclear war.

After the creation, in early 1947, of United World Federalists, the U.S. branch of the growing world federalist movement, Einstein served on its Advisory Board.

Einstein also promoted world federalist ideas through a burgeoning atomic scientists’ movement in which he played a central role. To bring the full significance of the atomic bomb to the public, the newly-formed Federation of American Scientists put together an inexpensive paperback, One World or None, with individual essays by prominent Americans. In his contribution to the book, Einstein wrote that he was “convinced there is only one way out” and this necessitated creating “a supranational organization” to “make it impossible for any country to wage war.” This hard-hitting book, which first appeared in early 1946, sold more than 100,000 copies.

Given Einstein’s fame and his well-publicized efforts to avert a nuclear holocaust, in May 1946 he became chair of the newly-formed Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, a fundraising and policymaking arm for the atomic scientists’ movement. In the Committee’s first fund appeal, Einstein warned that “the unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking, and thus we drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.”

Even so, despite the fact that Einstein, like most members of the early atomic scientists’ movement, saw world government as the best recipe for survival in the nuclear age, there seemed good reason to consider shorter-range objectives. After all, the Cold War was emerging and nations were beginning to formulate nuclear policies. An early Atomic Scientists of Chicago statement, prepared by Eugene Rabinowitch, editor of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, underscored practical considerations. “Since world government is unlikely to be achieved within the short time available before the atomic armaments race will lead to an acute danger of armed conflict,” it noted, “the establishment of international controls must be considered as a problem of immediate urgency.” Consequently, the movement increasingly worked in support of specific nuclear arms control and disarmament measures.

In the context of the heightening Cold War, however, taking even limited steps forward proved impossible. The Russian government sharply rejected the Baruch Plan for international control of atomic energy and, instead, developed its own atomic arsenal. In turn, U.S. President Harry Truman, in February 1950, announced his decision to develop a hydrogen bomb―a weapon a thousand times as powerful as its predecessor. Naturally, the atomic scientists were deeply disturbed by this lurch toward disaster. Appearing on television, Einstein called once more for the creation of a “supra-national” government as the only “way out of the impasse.” Until then, he declared, “annihilation beckons.”

Despite the dashing of his hopes for postwar action to end the nuclear menace, Einstein lent his support over the following years to peace, nuclear disarmament, and world government projects.

The most important of these ventures occurred in 1955, when Bertrand Russell, like Einstein, a proponent of world federation, conceived the idea of issuing a public statement by a small group of the world’s most eminent scientists about the existential peril nuclear weapons brought to modern war. Asked by Russell for his support, Einstein was delighted to sign the statement and did so in one of his last actions before his death that April. In July, Russell presented the statement to a large meeting in London, packed with representatives of the mass communications media. In the shadow of the Bomb, it read, “we have to learn to think in a new way. . . . Shall we . . . choose death because we cannot forget our quarrels? We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest.”

This Russell-Einstein Manifesto, as it became known, helped trigger a remarkable worldwide uprising against nuclear weapons in the late 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in the world’s first significant nuclear arms control measures. Furthermore, in later years, it inspired legions of activists and world leaders. Among them was the Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev, whose “new thinking,” modeled on the Manifesto, brought a dramatic end to the Cold War and fostered substantial nuclear disarmament.

The Manifesto thus provided an appropriate conclusion to Einstein’s unremitting campaign to save the world from nuclear destruction.

Image courtesy of US Govt. Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

by Lawrence Wittner | Feb 20, 2024 | Climate Justice, Disarmament

For some time, it’s been apparent that the world’s nations are not meeting the growing challenges to human survival.

A key challenge comes from modern war.

Over the centuries, as military weapons have grown ever more destructive, war-related devastation has grown accordingly. World War II was the deadliest military conflict in human history, with an estimated 70-85 million people perishing from the war directly or through war-caused disease, famine, and other indirect factors. Most of the dead were civilians. In addition, many millions of people were wounded―blinded, crippled, driven mad, or otherwise ravaged by the vast carnage. Large portions of the globe had become a charnel house, with the battered survivors left to desperately scavenge for food amid the burnt-out rubble and ruin.

Although some scholars have pointed out that warfare has declined since then, and especially since the end of the Cold War, there was a sharp turnabout in 2022, when the wars in Ethiopia and Ukraine contributed to more battle-related deaths than in any year since 1994. By late 2023, Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine alone had produced an estimated 315,000 killed or injured Russian troops, while the number of casualties among Ukrainian troops and civilians, though unknown, is certainly enormous. Among these and the many other wars currently raging―in Sudan, Myanmar, Ethiopia, the Sahel, and Syria, to name only a few―the recent one in Gaza, with the fastest daily death rate of the 21st century, is particularly alarming, having already led to nearly 30,000 deaths and nearly 70,000 injuries.

And then, of course, there’s nuclear war, which emerged in 1945 with the utter annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and which now has the capacity to end virtually all life on earth. Amid public threats from leaders of nuclear-armed nations to launch a nuclear war, the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists have set their “Doomsday Clock” at its closest ever to apocalypse.

War―particularly nuclear war―is probably the fastest way to extinguish the human race, but there are other crises underway that, on a longer-range basis, seem likely to accomplish the same task.

The most serious of these crises is environmental. In recent decades, there has been a rapid loss of biodiversity, with the sixth mass extinction of wildlife clearly accelerating. Pollution has grown dramatically. This includes pollution of land and water caused by chemicals and by plastic (which takes 400 years to decompose) and of the air caused by industrial, motor vehicle, and other emissions (leading to an estimated 4.2 to 7 million human deaths annually). Damage to the soil, caused especially by use of toxic chemicals and other pollutants, as well as by deforestation, has become particularly severe. The United Nations has estimated that some 40 percent of the planet’s soil is now degraded.

A key element in the environmental collapse is the growing climate catastrophe, caused primarily by the burning of fossil fuels. Melting icecaps and rising sea levels, unprecedented hurricanes, floods, and wildfires, and ocean acidification are all well underway. Together with unsustainable farming practices, rising temperatures have produced growing food and water scarcity. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres declared that, unless immediate action is taken, there will be a “global food emergency that could have long term impacts on hundreds of millions of adults and children.” Furthermore, it is estimated that, by 2025, two-thirds of the world’s people might face water shortages. Commenting on the deteriorating climate situation, Guterres declared gloomily in September 2023 that “humanity has opened the gates to hell.”

The rise of rightwing nationalism provides yet another challenge to human survival. In recent years, rightwing political movements―headed by authoritarian demagogues such as Donald Trump (United States), Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil), Vladimir Putin (Russia), Narendra Modi (India), Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Turkey), Marine Le Pen (France), Benjamin Netanyahu (Israel), Viktor Orban (Hungary), and their counterparts in other lands―have transformed the landscape of world politics. Appealing to xenophobia, militarism, racism, and religious prejudice, they have made great strides toward stirring up longstanding hatreds in their ruthless quest for power. A key to their success along these lines has been their call to revive the ostensible glory of their own nations by purging their internal enemies and triumphing over other, ostensibly inferior, countries abroad. Redolent of the fascist movements of the 1930s, this Radical Right approach portends worldwide turmoil, violence, and destruction.

Of course, it might not be too late to head off these developments. After all, in the twentieth century, humanity did manage to defeat the drive of the rightwing maniacs who established fascist regimes and launched vast wars to rule the world. In the aftermath of the chaos and destruction of World War II, humanity did manage to create the United Nations and to extend the range of international law. And, still later, as the planet stood on the brink of nuclear war, humanity did manage to roll back the nuclear menace and, for a time, halt the nuclear arms race and curb the prevalence of war.

Moreover, there are a great many efforts underway―by social movements and some far-sighted governments―to address the contemporary crises. Peace, environmental, and political action movements have flourished and brought forth demands for sweeping changes in public policy. In addition, some social movements, recognizing the global nature of the problems facing humanity, have called for enhanced global governance to cope with the severe threats posed by war, environmental devastation, and violations of human rights. The Summit of the Future on the horizon in September 2024 has been hailed as a “once in a generation” opportunity for meaningful reform of the global governance architecture. This watershed moment could be seized as a chance to correct course and avert disaster for humanity and the planet.

Even so, as the world once again veers toward destruction, it’s clear that it’s getting late―very late―to avert catastrophe.

Image Source: Doomsday Clock சஞ்சீவி சிவகுமார், CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

by Lawrence Wittner | Jan 31, 2024 | Peace

Although, according to the UN Charter, the United Nations was established to “maintain international peace and security,” it has often fallen short of this goal. Russia’s ongoing military invasion of Ukraine and the more recent Israeli-Palestinian war in Gaza provide the latest examples of the world organization’s frequent paralysis in the face of violent international conflict.

The hobbling of the Security Council, the UN agency tasked with enforcing international peace and security, bears the lion’s share of the responsibility for this weakness. Under the rules set forth by the UN Charter, each permanent member of the Security Council has the power to veto Security Council resolutions. And these members have used the veto, thereby blocking UN action.

This built-in weakness was inherited from the UN’s predecessor, the League of Nations. In that body, a unanimous vote by all member nations was required for League action. Such unanimity of course, proved nearly impossible to attain, and this fact largely explains the League’s failure and eventual collapse.

The creators of the United Nations, aware of this problem when drafting the new organization’s Charter in 1944-45, limited the number of nations that could veto Security Council resolutions to the five major military powers of the era―the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, China, and France.

Other nations went along with this arrangement because these “great powers” insisted that, without this acceptance of their primacy, they would not support the establishment of the new world organization. The Charter’s only restriction on their use of the veto was a provision that it could not be cast by a party to a dispute―a provision largely ignored after 1952. Fortifying the privileged position of these five permanent Security Council members, the Charter also provided that any change in their status required their approval.

In this fashion, the great powers of the era locked in the ability of any one of them to block a UN Security Council resolution that it opposed.

Not surprisingly, they availed themselves of this privilege. By May 2022, Russia (which took the seat previously held by the Soviet Union), had cast its veto in the Security Council on 121 occasions. The United States cast 82 vetoes, Britain 29, China 17, and France 16.

As the Council’s paralysis became apparent, proponents of UN action gravitated toward the UN General Assembly. This UN entity expanded substantially after 1945 as newly-independent countries joined the United Nations. Moreover, no veto blocked passage of its resolutions. Therefore, the General Assembly could serve not only as a voice for the world’s nations, but as an alternative source of power.

The first sign of a shift in power from the Security Council to the General Assembly emerged with the General Assembly’s approval of Resolution 377A: “Uniting for Peace.” The catalyst was the Soviet Union’s use of its veto to block the Security Council from authorizing continued military action to end the Korean War. Uniting for Peace, adopted on November 3, 1950 by an overwhelming vote in the General Assembly, stated that, “if the Security Council, because of lack of unanimity of the permanent members, fails to exercise its primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security . . . the General Assembly shall consider the matter immediately with a view to making appropriate recommendations to members for collective measures.” To facilitate rapid action, the resolution created the mechanism of the emergency special session.

Between 1951 and 2022, the United Nations drew upon the Uniting for Peace resolution on thirteen occasions, with eleven cases taking the form of the emergency special session. In addition to dealing with the Korean War, Uniting for Peace resolutions addressed the Suez confrontation, as well as crises in Hungary, Congo, Afghanistan, Palestine, Namibia, and Ukraine. Although, under the umbrella of Uniting for Peace, the General Assembly could have recommended “armed force when necessary” against violators of international peace and security,the Assembly adopted that approach only during the Korean War. On the other occasions, it limited itself to calls for peaceful resolution of international conflict and the imposition of sanctions against aggressors.

These developments had mixed results. In 1956, during the Suez crisis, shortly after the General Assembly held a Uniting for Peace session calling for British and French withdrawal from the canal zone, both countries complied. By contrast, in 1980, when a Uniting for Peace session called for an end to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Moscow ignored the UN demand. It could do so thanks to the fact that General Assembly resolutions are mere recommendations and, as such, are not legally binding.

Even so, global crises in recent years have heightened pressure to provide the United Nations with the ability to take effective action. In April 2022, shortly after the Russian government vetoed a Security Council resolution calling for Russia’s unconditional withdrawal from Ukraine, the General Assembly voted that, henceforth a Security Council veto would automatically trigger a meeting of the Assembly within ten days of the action to cope with the situation.

Meanwhile, numerous nations have been working to restrict the veto in specific situations. In July 2015, the UN Accountability, Coherence, and Transparency Group proposed a Code of Conduct against “genocide, crimes against humanity, or war crimes” that called upon all Security Council members to avoid voting to reject any credible draft resolution intended to prevent or halt mass atrocities. By 2022, the Code had been signed by 121 member nations. France and Mexico have taken the lead in proposing the renunciation of the veto in these situations.

These reform initiatives are likely to be addressed at the September 2024 UN Summit of the Future.

Clearly, as the history of the United Nations demonstrates, if the world organization is to maintain international peace and security, it must be freed from its current constraints.

This article was originally published in PeaceVoice.