Mondial Article (Winter 2025)

A Tale of Two Summits: Civil Society’s Role in the UN’s Summit of the Future

Hannah Fields

Hannah Fields is the Communications Officer at CGS. She is also a communications and digital content specialist with over ten years of experience working in the nonprofit, global health, and higher education sectors. She has supported organizations, such as Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Political and Social Science, with editorial projects, digital content management, and a broad range of communications outreach.

In the last issue of Mondial, we brought you a preview of the United Nations (UN) Summit of the Future. Conceptualized by UN Secretary General António Guterres in his 2021 Our Common Agenda report, the Summit was labeled as a “once-in-a-generation opportunity to reinvigorate global action, recommit to fundamental principles, and further develop the frameworks of multilateralism so they are fit for the future.”

Overcoming threats that it might be sidelined entirely, 130 heads of state and government convened for the Summit at the UN headquarters in New York City in September 2024 to reinvigorate multilateralism and reform global governance. They also met in the shadow of devastating conflicts in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, and with looming urgency to address compounded environmental crises faced globally.

Despite the grim geopolitical outlook, an energetic buzz of advocacy preceded the Summit itself. While the Summit was originally foreseen as concurrent with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) conference the previous September, a longer onboard ramp allowed civil society to step up throughout the process despite obstacles.

Official access to Member State negotiations was limited throughout the lead-up to the Summit, and travel limitations (including visa restrictions and financial implications) further curtailed civil society participation. Yet, thanks to the commitment and mobilization of coalitions, such as the Coalition for the UN We Need (C4UN), a ripple spread from New York to Nairobi, where the first-ever UN Civil Society Conference to be convened in Africa was held in May 2024.

The Nairobi conference was the first to be directly connected to a UN intergovernmental process and the first to occur in the Global South. Throughout the conference, dissatisfaction with the organizational inertia of institutions to enact meaningful change in the wake of polycrisis, permacrisis, and planetary crises was clear, ruling the global response as fundamentally broken. However, through wide-ranging delegations and conversations, multilateralism emerged as the key to ushering in a global collective response to current and future global challenges. This idea took shape in the creation of 20 multistakeholder ImPACT Coalitions (ICs) leading to the Summit of the Future. These coalitions represent civil society, international organizations, governments, and the business community meeting to address peacebuilding, international financial reform, funding community building, and more. These ICs also show the need for civil societies to regularly convene with multilateral institutions to ensure those institutions and their members progress effectively on commonly agreed priority goals and commitments.

Ultimately, more than 10,000 civil society representatives gathered on September 20 and 21 for the Summit of the Future Civil Society “Action Days.” During this time, many ImPACT Coalitions (several of which Citizens for Global Solutions (CGS) is actively involved) and other groups hosted dozens of side events, engaged in critical advocacy with Member States, and met—often for the first time—with fellow advocates worldwide. A day or two before the conference, civil society could no longer realistically expect to influence its primary outcome documents: the Pact for the Future and its annexes, the Declaration on Future Generations and Global Digital Compact, together meant to “protect the needs and interests of present and future generations.”

Conversely, this civil society meeting allowed participants to discuss the many themes outlined in the first two revisions of the Pact for the Future, which included 56 proposed actions and commitments by the UN’s 193 Member States. In these revisions, Namibian and German co-facilitators sought to ensure dedicated actions on gender equity, human rights, and sustainable development in the Pact’s five chapters. As demonstrated by the Action Days, the utilization and participation of civil society reveals an essential key for the UN to effectively go further in these areas and create future pathways to bringing about a more effective, accountable, and inclusive global governance architecture.

While addressing these ideals seems like a Sisyphean task, former UN Deputy Secretary General Mark Malloch Brown reflected on his years of experience, sharing that some ideas may take decades to implement but can still be implemented in the most unlikely situations: “There is a lazy default assumption that when the world’s politics are broken down, there is no point in trying to reform the multilateral institutions because they are going to mirror that political discord. As a veteran of this thing, I’ve seen that you can squeeze through interesting reforms precisely because of that conflict.”

And conflict there was—notably in the form of the dramatic 11th-hour threat to derail the Pact led by Russia. A representative from the Russian Federation preceded the amendment by stating that “no one is happy with this text,” before presenting its objection to 25 provisions in the draft pact. This included asserting primacy of national jurisdiction and rejection of language on universal access to sexual and reproductive health rights, as well as gender empowerment more broadly. The amendment was immediately met with backlash, with the representative for the Republic of Congo, speaking for the African Group, stressing that the adoption of such an amendment would not meet the Summit’s expectations of reaching solutions to today’s multiple, complex challenges through unity. He then proposed the amendment be rejected. His motion was adopted by a recorded vote of 143 in favor to seven against (Belarus, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Iran, Nicaragua, Russian Federation, Sudan, Syria), with 15 abstentions.

Despite the agitation of spoilers, the Pact was secured. Most notably, the Summit’s 26-page outcome document (on its third revision) recognized the need to redress the historical injustice and underrepresentation of Africa in the UN Security Council and laid out a roadmap for Security Council reform; it committed to protecting the needs and interests of future generations; it included the first international agreement on governance of artificial intelligence; and it called for increasing the voice of developing countries in the decision-making governance of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

Even so, multilateralism and the much-hoped-for ambitions of the Pact were only preserved with modest advances toward reform with room for improvement. Some disappointments included a watering down of language concerning international environmental governance (Actions 9 and 10) and the removal of Action 32, which would have facilitated critical tech transfers to developing countries while safeguarding intellectual property rights. The cutting of the term “Emergency Platforms” (Action 54) also came as a setback, as this hinders the use of a true multilateral system capable of convening both States and non-State actors to respond to global crises.

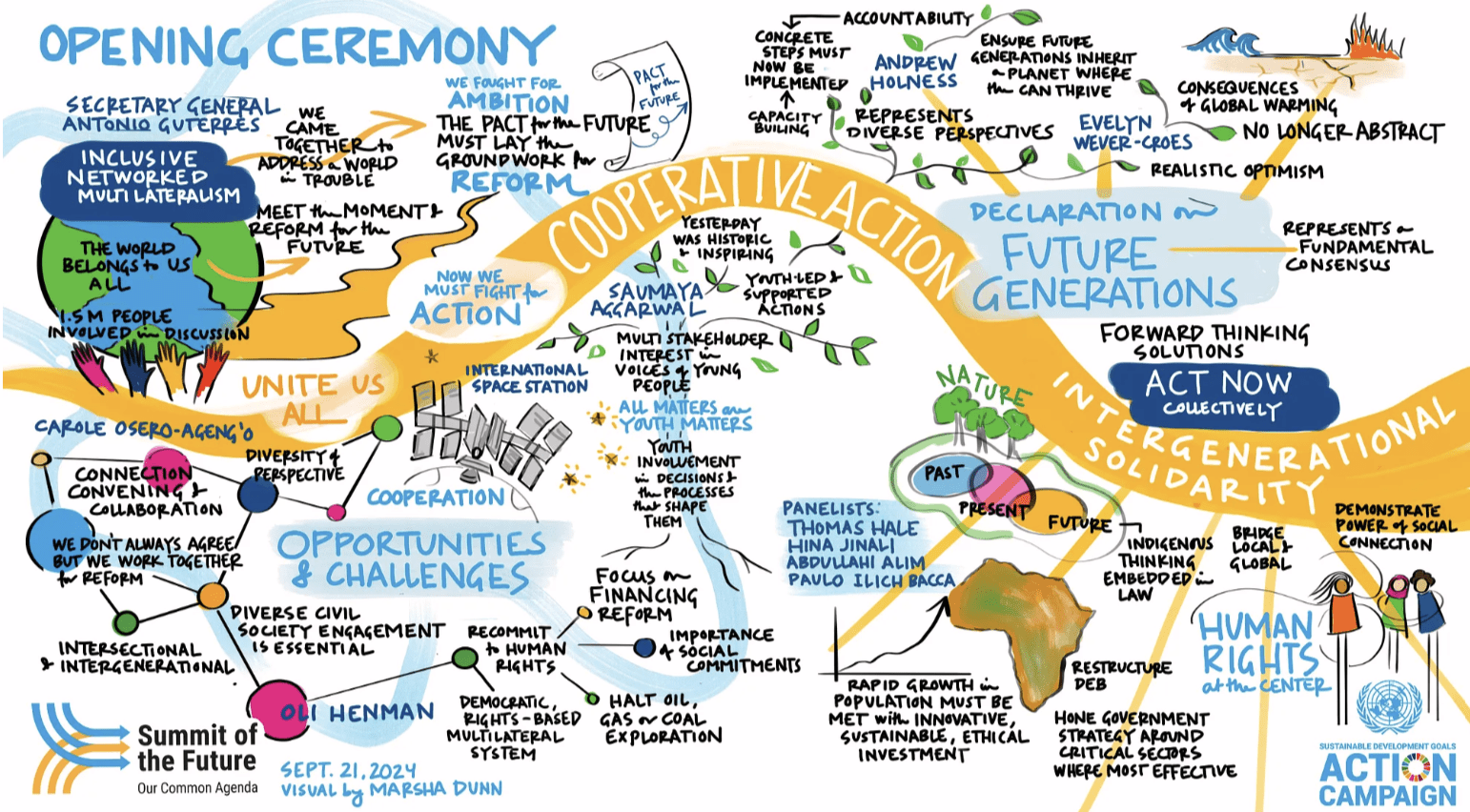

Visual summary of the Opening Ceremony of the Summit of the Future. Source: UN SDG Action Campaign.

Heba Aly, coordinator of the UN Charter Reform Coalition and senior adviser at the Coalition for the UN We Need (C4UN), reflected on these disappointments. “[The Pact] could have been improved by Member States recognizing that the world is in crisis and needs a fundamental reset and that, ultimately, international cooperation and compromise are in the interest of all countries,” Aly explained. “This might have created an environment in which the more ambitious reforms proposed by civil society in the People’s Pact for the Future, organized by C4UN with inputs from a wide array of civil society actors, could have been explored. The Summit could also have been improved by allowing civil society to participate in the negotiations.”

The People’s Pact for the Future represents nearly two years of work among civil society organizations using online, regional, and global consultations to present a multilateral approach to meeting the needs of humanity and the planet today. It contains recommendations driven by five key objectives: a longer-term future orientation, global institution reform, a whole-of-society approach, meeting existing commitments, and building trust. In addition, the pact focuses on seven themes based on a combination of the pillars of the UN and tracks identified in the Our Common Agenda report. They include SDGs and development, UN Charter reform, environmental governance, human rights and participation, the Global Digital Compact, the global economic and financial architecture, peace and security, and UN and global governance innovation.

The People’s Pact also calls on the UN to recommit to the aspirations outlined in the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The document states that the international community must shift from defending state centrism to “rebalancing decision-making to the local, national, regional, and global levels, under the principle of subsidiarity.” The People’s Pact will serve as a critical tool in advocacy and a barometer of progress as the Pact for the Future review conference looms in 2028.

It is in the People’s Pact where the importance of civil society becomes most evident, as a multilateral system cannot exist without its meaningful participation. Since their recognition as Major Groups and Stakeholders in 1992, civil society has played a significant role in the UN system, advocating for marginalized groups, shaping international agreements, and monitoring state compliance with UN resolutions. However, some Member States still view civil society as playing a more consultative role rather than recognizing the critical value of civil society as a partner in policymaking. The UN must be willing to evolve for the multilateral system to evolve, and invite—ideally, encourage—civil society to participate fully in its summits, resolutions, and reforms.

One example is the call for a comprehensive update of the UN Charter by civil society leaders and ImPACT Coalitions, such as the UN Charter Reform Coalition. The UN Charter Reform Coalition urges that Article 109 be invoked to call a charter review conference, thereby starting a deliberate diplomatic process that could fundamentally reshape and federalize relations between Member States. The UN Charter was intended to be a living document, and the Article 109 process is its built-in mechanism for comprehensive reconsideration of the 1945 negotiated text, including, but not limited to, the Security Council.

This Article 109 process should allow civil society to actively participate in what those changes might look like, as civil society is more closely aware and connected to what the world needs from a more equitable, effective, accountable, and inclusive United Nations. And for that, there is hope for a better future beyond the Summit.

“From New York to Nairobi to back again, we’ve seen a coming together of civil society with Member States to advance promises and aspirations of the UN Charter,” reflected CGS Executive Director Rebecca Shoot. “In doing so, we have renewed appreciation that our global governance institutions, indeed even the Charter itself, are not preserved in amber, nor are they so brittle or so fragile that if we touch them, they will break. We are reminded instead that they are human-made works in progress.”

Now that the space for action has been created, it is up to coalitions, Member States, and related organizations to work with the same energy and ambition to ensure the Pact’s most significant proposals and reforms are implemented. With the UN approaching its 80th anniversary in 2025, and a new Secretary General taking office in 2027, there are significant milestones to be both assessed and achieved leading up to the mandated September 2028 Pact for the Future progress review. These milestones can be best achieved when Member States allow broader constituencies, especially civil society, to have a seat at the table.

Mondial is published by the Citizens for Global Solutions (CGS) and World Federalist Movement — Canada (WFM-Canada), non-profit, non-partisan, and non-governmental Member Organizations of the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Government Policy (WFM-IGP). Mondial seeks to provide a forum for diverse voices and opinions on topics related to democratic world federation. The views expressed by contributing authors herein do not necessarily reflect the organizational positions of CGS or WFM-Canada, or those of the Masthead membership.