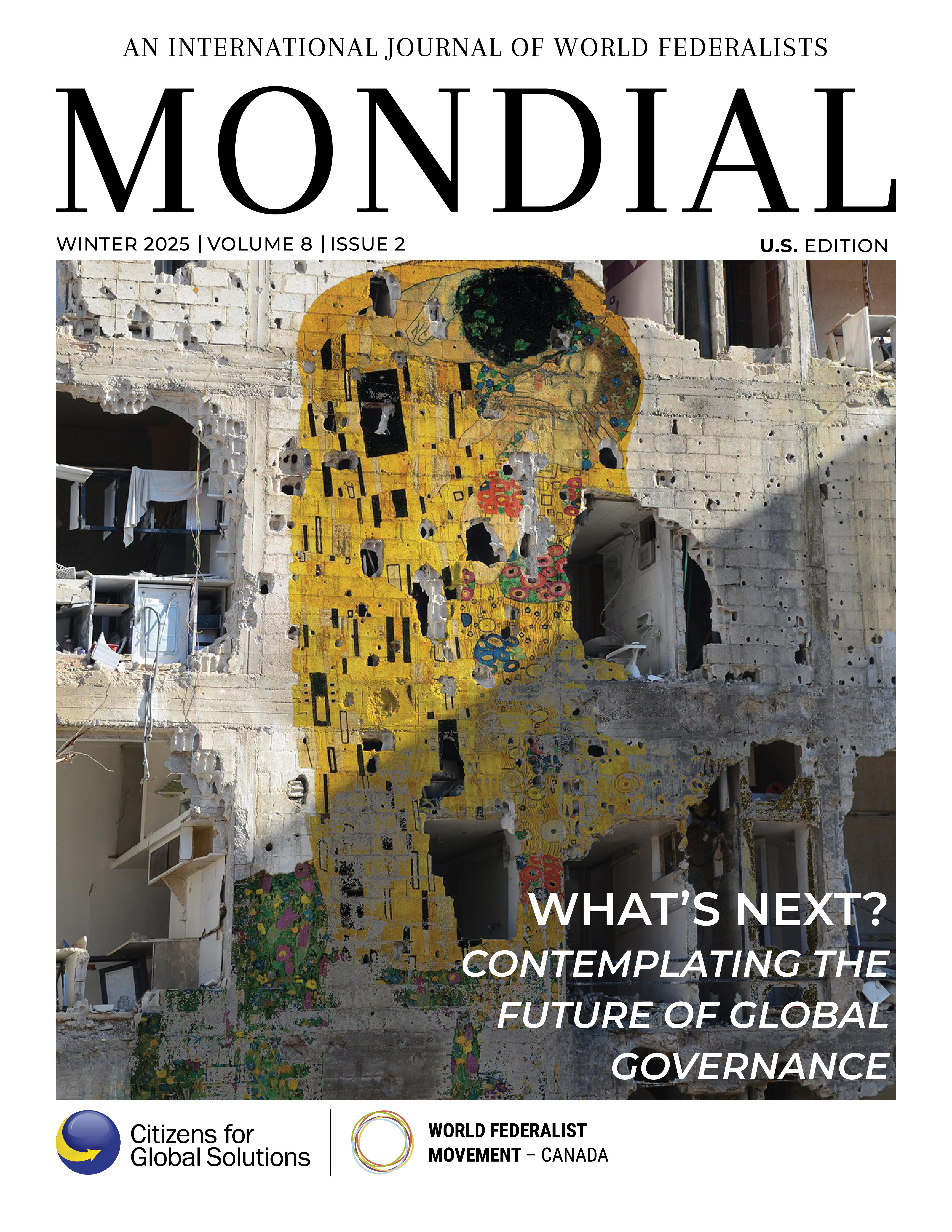

Mondial Article (Winter 2025)

Solving the UN’s Liquidity Crisis: Radical Thinking

David Woollcombe

David Woollcombe is the founder of Peace Child International. He has championed youth engagement for more than 40 years and specializes in making complex topics understandable to young people and others. Among his contributions to youth engagement in the vital issues of our time, David wrote and produced the play “Peace Child,” created the children’s edition of the Rio Agenda 21 “Rescue Mission: Planet Earth,” and organized the six World Youth Congresses. David now works as a consultant on youth employment, citizen diplomacy and climate change issues for a number of organizations in the United Kingdom and globally. He has stood three times as a Green Party candidate for Hertfordshire and represents East Herts as a Local Councillor.

In January 2024, United Nations (UN) Secretary General António Guterres wrote a letter to all UN Member State representatives that must have been uncomfortable for him to write. He told them: “Over the course of the last year, the cash situation [at the UN] has morphed into a full-blown liquidity crisis. As a result, I am forced to implement aggressive cash conservation measures to avert a default.” The core problem, he explained, was that “not all Member States pay their assessed contributions in full. In 2023, we collected only 82.3% of the assessments, causing our year-end arrears to rise from $330m to $859m. Additionally, we had to return $114m to Member States as credits. We survived because we started the year with $700m in cash reserves. We started 2024 with $60m and now anticipate running out of all cash by August 2024.”

As of late November 2024, there was no confirmation of that dire prediction. One hundred forty-seven Member States have paid their assessed contributions, leaving 46 that have not, of which the largest, the United States and China, owed $3 billion and $2 billion respectively.

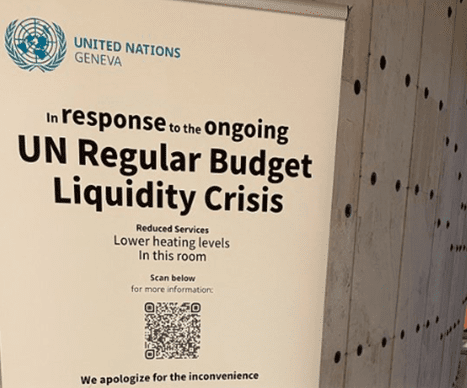

This liquidity crisis comes at a time when the UN system is actually spending more than ever before: $74 billion in 2022 — up from $40 billion a decade ago. The trouble is that over 80% of that budget is in “earmarked funds” that member states and others designate for spending through certain agencies, often on specific projects within those agencies. Administrative overheads and core salaries are paid for by “assessed contributions” — which is where the UN is seriously cash-stressed. The Secretariat has had to impose a hiring freeze and energy saving measures plus severely curtail official travel, use of consultants and construction projects.

Bad as the figures are, the reputational damage for the UN is perhaps worse: every day, staff and visitors to the UN see empty offices, positions unfilled, escalators turned off and meetings cancelled or transferred online to save funds. This gives rise to rumors, such as: “The UN is broke!” Very few Member States want that, and neither does the public. Pew Research found that, in 35 countries, “58% have a favorable, and 31% a negative view of the organization.” Despite the emergence of other entities, like the G20 and BRICS+, most agree that the UN is the only game in town and must be preserved. As the Secretary General says at the end of his letter: “We simply must find a lasting solution for these recurring liquidity problems.”

Let us review what he, and others, have suggested those “lasting solutions” might be.

The UN Premises in Geneva feels the cold of reduced funding.

Currently Consisered Solultions

The Secretary General’s solution is to “urge all Member States to meet their financial obligations in full.” The two words that he, as a diplomat, is far too polite to include are: “or else!” Currently, the “or else” lies in Clause 19 of the UN Charter, which states: “A UN Member State which is two full years in arrears in the payment of its financial contributions shall have no vote in the General Assembly.” This penalty is clearly too timid. In the business world, customers have to settle invoices within 30 days or face penalties and, ultimately, court proceedings. The UN should impose indicative penalties on Member States that fall three or six months in arrears—things like: exclusion from the Members’ dining room, chairmanship of committees or a loss of the right to vote in the General Assembly and Security Council. This might embarrass permanent representatives of non-paying Member-States sufficiently to urge their capitals to pay their dues.

International researchers and think tanks have several other solutions:

1. Regulate earmarking / strengthen assessed contributions: An essential first step. The International Peace Institute’s Global Observatory (IPI Global Observatory) reveals that 88% of the 2022 income of the UN Development Programme (UNDP) income was earmarked. For the UN International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), that number was 87%, and for the World Food Programme (WFP), 97%. This requires UN Agencies to become non-stop fundraisers and to engage in a competitive chase after voluntary contributions, which results in a “more atomized UN family, with more duplication and turf wars.” It also, inevitably, leads UN Agencies to undertake projects for which funding is available, forsaking those that their mandates require. The Secretary General’s proposed “Funding Compact” demands that donors pool their earmarked contributions into interagency funds; but that idea has considerable pushback from both donor and recipient countries that prefer the cozy system of financial patronage that the current system gives them. At the very least, the Secretary General should require earmarked funds pay a higher percentage of their total to overheads.

2. Mergers and “Delivering as ONE”: A FUNDS Report by Stephen Browne and Thomas Weissman recommends setting up an Independent Funding Commission to identify duplication and recommend mergers. They point out that:

- Three UN agencies are responsible for Food & Agriculture: the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and WFP;

- Six UN-related agencies collect data on trade: the International Trade Commission (ITC), UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), as well as the following bodies connected to the UN: the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and the World Trade Organization (WTO);

- Twenty-nine agencies have programs on water; and

- Four agencies have programs on maternal health: UN Population Fund (UNFPA, UNICEF), UN Women, and the World Health Organization (WHO);

This results in meetings at which the leaders of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) leaders like myself watch aghast as hours of debate are wasted on discussions as to which agency has responsibility for what. “Stop it!” We want to cry. Sometimes they do, and talk piously about cost effectiveness and “delivering as one.” An early sign that they might actually do this is the planned move of some UN agencies to an expanded UN campus in Nairobi, as rents there are much lower than in Manhattan.

3. The EU Method: Several interesting ideas for new Funding Mechanisms were raised in a 2020 Publication by Augusto Lopez Claros, Maja Groff, and Arthur Dahl, starting with that used by the European Union. The European Union (EU) system has each member state paying a fixed percentage of their Gross National Income (GNI) plus value added tax (VAT) receipts. Payments are automatically deducted at source and Member States are not allowed to withhold contributions even if they disagree with policy. Also, the Budget is set for seven-year cycles whereas the UN operates on annual budgets. But, the EU is comprised of only 27 countries with long, shared histories, similar economies, culture,s and tax systems. Direct comparisons with the UN are thus probably fanciful.

4. A Tobin Tax: Another possibility explored by Claros, Groff, and Dahl—and many others before them —is the financial transactions tax proposed by James Tobin. It builds on the 1936 proposal of John Maynard Keynes for a general financial transaction tax which, he argued, would dampen the reckless speculation or “casino capitalism” of financial markets. Tobin himself did not give much thought to what to do with the annual revenue raised by the tax on transactions. But the tax’s supporters quickly did the math, and realised that a 0.05% tax on the world’s $1.3 trillion daily transactions would yield approximately $600 billion a year—more than enough to deliver on every UN mandate for peacekeeping, education, health-, shelter, water, and nutrition-for-all.

5. The Schwartzberg Proposal: The most promising proposal we have seen to date is also the simplest. As proposed by Joseph Schwartzberg in his 2013 study, “Transforming the United Nations System: Designs for a Workable World,” the UN would assess Member State contributions at a fixed percent of their peoples’ average per capita income. The result would be that wealthy countries like Liechtenstein, Monaco, and Qatar would contribute a lot more per capita than, say, China, Sierra Leone, or Nigeria. But everyone would consider it to be fair and it would eliminate the complexity that baffles this author and many of the diplomats to whom I have spoken. It would also eliminate the need for “earmarked funds,” which would allow the UN to pursue its core mandates, not the pet projects of wealthy individual Member States and their “donor darling” client states. The World Bank reports that total world income in 2023 was about $100 trillion: 0.01% of this would be $100 billion, considerably more than the UN spent last year.

UN Secretary General António Guterres and President Vladimir Putin met at the BRICS+ Summit, in Kazan, Russia, on October 24, 2024.

Radical Solutions―and How To Make Them Happen

At the first meeting of the UN General Assembly in London in January 1946, the British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, praised the authors of the UN Charter, saying how pleased he was that it was set up in the name of “we the peoples,” not “we the governments.” But he was mistaken; the UN is – and always has been – a “we the governments” organization. So, if “he who pays the piper calls the tune,” “we the peoples” cannot complain that we don’t get much of a say in how the organisation is run or the decisions it takes.

1. Monetizing the UN: In the run-up to the UN Summit of the Future, several calculated that the current global tax revenue is insufficient to meet the budget required to deliver the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, or any of the other great missions that the UN has promised to deliver. So what might we the peoples do to raise the funds needed? Could we the peoples monetize the UN and thus take a bigger role in paying the UN piper and calling its tune?

Think about it. Although there is massive popular support for addressing the climate crisis, few governments dare to inflict any pain on the public or tax the fossil fuel companies that have been making a billion dollars a day in profit since the 1990s. Some governments also subsidize those companies to continue their fossil fuel production to the tune of $5.23 trillion a year. We the peoples, especially young people, blanch in rage when they hear those numbers. The climate emergency demands that cash mountain be spent on ensuring the survival of future generations. One way of doing this would be to make the UN the hub of a global carbon trading scheme, like the one set up by the European Commission. It would trade government-to-government and business-to-business carbon credits, but it could go further and set up a Personal Carbon Budget (PCB) trading scheme. PCBs would take the current carbon emissions budget recommended by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) required to stay below the 1.5 degree threshold, divide it between the 8 billion inhabitants of planet earth and trade it accordingly. Inhabitants of the industrialized north who want to maintain their high-carbon lifestyles would have to purchase carbon credits from individuals in the global south, thus transferring huge amounts of cash from north to south, and massively incentivising a rapid transition to renewable sources of energy, while simultaneously providing some economic and climate justice duly owed. It would also raise billions in handling fees by the UN. Fanciful? Probably. But the unhappy outcome of the Baku Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP) suggests that, in the lifetimes of the young people going through our schools and universities today, they will have to create new global institutions to deliver the very expensive climate solutions if future generations are to live in the safe, sustainable world that Secretary General Guterres described in his letter to his great granddaughter.

2. Create a new UN that Works! Nowhere in that letter — nor in any of the discussions leading up to the Summit of the Future – did he or anyone raise this radical but obvious idea for a solution: creating a UN that –

- boldly addresses the growing conflict between the unipolar US-led G7/NATO alliance and the multipolar anti-Western BRICS+ alliance led by Russia and China.

- finds a way to override the vetoes of Russia and the US to end the carnage in Ukraine and Gaza;

- delivers a world free of nuclear weapons, as it has tried to do these last 80 years; and

- solves the climate crisis and delivers on its oft-repeated promises of education-for-all, health-for-all, and food & shelter-for-all.

Why should member governments, or anyone else, throw good money after bad at an organization that has so clearly failed to deliver the global services it was set up to provide? Sir Partha Dasgupta began his Biodiversity Review, an independent study commissioned by the government of the United Kingdom, by noting:

The UN, as presently constituted, is clearly not that infrastructure. Secretary General Guterres appeared to acknowledge that fact when he told a panel of young people at the opening of the Summit of the Future: “Our generation messed up,” adding, darkly, “Great powers never give up their power; it has to be taken.” By this he meant, what we all know and which the Summit of the Future did not really address: we have to revise the UN Charter, eliminate the P5 Veto, and recognise the rights and voice of the global south. A UN paid for by the global north is never going to genuinely work for the interests of the majority of the world’s people. Likewise, a UN paid for by the elders of today is never going to prioritize the interests of future generations whatever the UN’s well-meaning Declaration says. So reform or re-invention is imperative. But how?

3. Where to begin? Tell a plausible story of how young people might make UN Reform happen.That is what “Peace Child” has done these last 40 years – and several of our stories have become self-fulfilling prophecies. The original “Peace Child” story told how a friendship between a young American boy and a Russian girl persuaded their presidents to become friends and end the Cold War. Within a decade, Reagan and Gorbachev had done just that and the Iron Curtain fell. In 2008, a “Peace Child” called “Kids on Strike!” was created by a youth group in Rochester, New York. It told a story of how kids came out on strike to force their governments to solve the climate Emergency. Ten years later, Greta Thunberg made the story real.

In the Pact for the Future, our governments promised to “safeguard the needs and interests of future generations.” So next year’s new P5 Peace Child Project will bring young people from each of the P5 nations to co-create a story that has the UN bringing together P5 leaders to explore solutions to the planetary boundary issues which they must solve together. How will they do it? Peace Child has faith that young people, guided by elder professionals, will figure it out. In 45 years, they have never let us down. And, at the heart of every Peace Child story is a UN-like body that is owned, financed and operated by “we the peoples” of the whole world – working to ensure that we are all “good ancestors” who prioritise the needs of generations yet unborn.

Mondial is published by the Citizens for Global Solutions (CGS) and World Federalist Movement — Canada (WFM-Canada), non-profit, non-partisan, and non-governmental Member Organizations of the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Government Policy (WFM-IGP). Mondial seeks to provide a forum for diverse voices and opinions on topics related to democratic world federation. The views expressed by contributing authors herein do not necessarily reflect the organizational positions of CGS or WFM-Canada, or those of the Masthead membership.