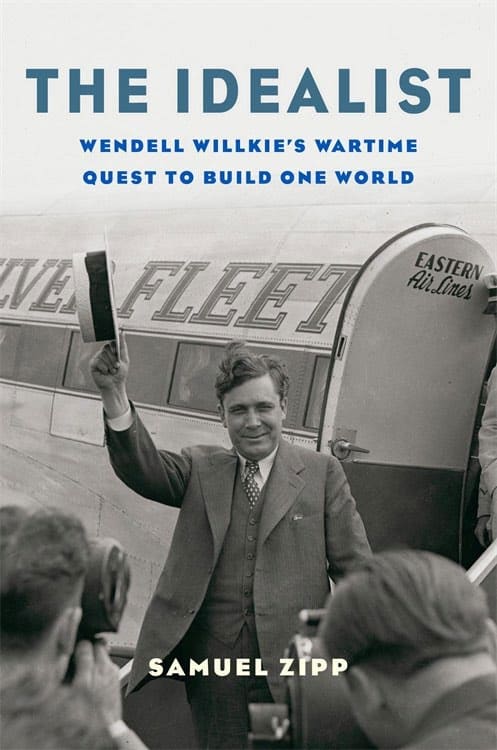

The Idealist:

Wendell Willkie’s Wartime Quest to Build One World

by Samuel Zipp

The Idealist: Wendell Willkie’s Wartime Quest to Build One World by Samuel Zipp

Wendell Willkie – successful lawyer and businessman, as well as a defeated candidate for U.S. President on the Republican Party ticket in 1940 – is a largely forgotten figure today. But, as Samuel Zipp reminds us, Willkie was extremely influential during World War II, when he launched a popular campaign for “global interdependence” or, as it became known, “One World.”

In this beautifully written and well-researched book, Zipp, Professor of American Studies at Brown University, points out that, unlike the conservatives and isolationists in his party, Willkie was a liberal who had backed Woodrow Wilson’s call for a League of Nations, advocated racial equality, and usually supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s policy of collective security.

Indeed, with World War II well underway, he and Roosevelt hatched a plan to have Willkie embark on a worldwide goodwill tour, by aircraft, from August to October 1942. This well-publicized venture was designed to demonstrate America’s political unity in wartime, foster support for the Allied powers, and provide a source of information on governmental and public opinion abroad.

Willkie – an informal, garrulous, likable individual with a common touch – not only had great success along these lines, but was powerfully influenced by what he saw. Appalled by imperialism and racism and impressed by the demand for freedom of colonized or subordinate people in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, Willkie returned, as Zipp notes, convinced of the need to get Americans “to see the wider world through the lens of fraternity and cooperation.” He hoped to convince them that their independence “would require a new form of interdependence with the world,” one in harmony with “global desires for an end to empire and a guarantee of self-determination.”

Back in the United States, Willkie embarked on a round of interviews, speeches, and articles along these lines, capped off by the publication of an immensely popular book, One World. With sales topping 1.6 million copies by July, some observers called it the best-selling book in U.S. history. Furthermore, that June, more than 100 newspapers in the United States and abroad, with a combined circulation of over seven million readers, ran an abridged version in their pages. Using his celebrity status to assail both “narrow nationalism” and “imperialism,” Willkie produced what Zipp calls “a fleeting moment,” when he “showed the country an alternative possible future.”

But, the moment passed. Nationalists and imperialists began to criticize this vision, the Republican Party repudiated his leadership, and in October 1944, Willkie – at only 52 years of age – died of a heart attack. Although, after the atomic bombing of Japan, world federalist and nuclear disarmament groups adopted “One World or None” as their slogan, the idea of egalitarian global interdependence gradually lost favor, despite its occasional revival by environmentalists and others.

Even so, Zipp concludes, Willkie’s “diagnosis of the value of global interdependence has never been more prescient,” while “his warnings about the perils of racially charged ‘narrow nationalism’ have never been more indispensable.”

Dr. Lawrence S. Wittner

Professor Emeritus, State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany; CGS Board Member

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Samuel Zipp, author of The Idealist: Wendell Willkie’s Wartime Quest to Build One World.

Samuel Zipp

Samuel Zipp is a writer and historian. He is the author and co-editor of three books on American culture and history. He has written articles and reviews for The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Nation, n+1, The Baffler, Metropolis, Cabinet, In These Times. He lives in Providence, Rhode Island, where he is Professor of American Studies and Urban Studies at Brown University.

What’s your motivation for writing the book?

“I found my way into The Idealist through the back door. As a cultural and urban historian of the 20th century United States, I had written about the building of the headquarters of the United Nations in New York City, and from that research I had become aware of the intense interest that many middle of the road Americans had in internationalism during and after World War II. I was curious about the origins and fate of these ideals, and their place in the larger political culture of the time, surrounded as they were by intense nationalism to their right, and, to their left, a marginalized but prescient form of anti-racist, anti-imperialist criticism of American power and capitalism.

Reading Wendell Willkie’s One World for the first time I was struck by how forthrightly he grappled with nationalism and how much he had borrowed from the campaigners to his left. Willkie himself was usually just written off as an also-ran, a flash in the pan whose role in history was simply to play help-meet to FDR as the President took the US into the war and then to the commanding heights of global power. But One World and its popularity suggested that there was a different history here – of failure and of a vision cut short when Willkie died prematurely in late 1944, of course – but also of a prescient analysis of the way that the US was enmeshed in the world. That’s the lesson I began to see as I told the story of Willkie’s trip around the world in 1942, the “one world” boom of 1943 and 1944 and its partial realization in the founding of the United Nations, and the ultimate eclipse of his ideals under the gathering currents of the Cold War to come. Ultimately, I think Willkie’s rough encounter with the forces of empire and racism during World War II reveal lost possibilities and warnings from an era when his vision of an internationalist US commanded a large popular audience. I’ve hoped to render those times in a broadly accessible narrative that doesn’t shy away from deep political and cultural context, attention to the lives and challenges faced by people in the places he visited in 1942, and a healthy skepticism about the just so stories Americans tell themselves about World War II.”