Mondial Article (Summer 2024)

The Forgotten Crime:

Forging a Convention for Crimes Against Humanity in 2024

Leila Sadat

Leila Sadat was the Special Adviser on Crimes Against Humanity to the International Criminal Court Prosecutor from 2013-2023 and is the Director and founder of the Crimes Against Humanity Initiative. She is a member of the CGS National Advisory Council.

The international legal order is awash with treaty mechanisms – for terrorism, corruption, and even cutting submarine cables – that offer “horizontal systems” for addressing crime. Shockingly, no equivalent system exists for crimes against humanity, leaving a major legal and impunity gap. In 2024, that could change with the culmination of years of work by civil society, legal experts, supportive Member States, and UN officials, notably including the UN International Law Commission’s Special Rapporteur on Crimes Against Humanity, Sean D. Murphy. It is imperative that these efforts come to fruition to achieve a system of accountability capable of confronting the gravest crimes.

Background on Crimes Against Humanity

The history of crimes against humanity can be traced back to the 19th century, but they became prominent in 1945 during the Nuremberg trials, when Nazis were prosecuted for their crimes during the Holocaust. Since then, there has been piecemeal codification of crimes against humanity through several international treaties. The most prominent of these is the Genocide Convention, which is often what we think about when we think about mass atrocity.

The contemporary definition of crimes against humanity comes from the 1998 Rome Statute that established the International Criminal Court (ICC). Having participated in the Rome Conference, I witnessed the miracle that gave the world a court that is permanent and operates in real-time. The ICC’s definition of crimes against humanity was premised on customary international law, taking into account the precedents of the ad hoc international criminal tribunals, including the Nuremberg Tribunal and the UN Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. It was challenging to develop it during the Rome Conference, because no treaty on crimes against humanity was yet in force, unlike genocide and war crimes.

Crimes against humanity are especially critical to the ICC’s capacity for prevention, creating a mechanism to halt what I call “atrocity cascades” of increasingly severe violence. Often, a situation that begins with human rights violations that can develop into a case of crimes against humanity, then war crimes, and ultimately genocide (sometimes all three happen at the same time). Because the ICC works in real-time, it can hold perpetrators accountable for human rights violations that escalate up to a certain level without waiting for armed conflict to break out. Accordingly, crimes against humanity have accounted for 30 percent of ICC cases, as opposed to the ad hoc tribunals, where independent charges for crimes against humanity were rare.

If the ICC has the means to effectively investigate and prosecute crimes against humanity, one might ask why a stand-alone treaty is necessary.

The Importance of a Crimes Against Humanity Treaty

The ICC has jurisdiction over individual perpetrators of the crimes under its jurisdiction: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the Crime of Aggression. Conversely, human rights treaties and other multilateral instruments governing international crimes concern State conduct. They provide a mechanism for victims to achieve justice against government actors for violations of their legal obligations. The ICC also takes very few cases, leaving most mass atrocities to be addressed by national systems.

A Crimes Against Humanity Treaty would require States Parties to take affirmative action to prevent and punish crimes against humanity – obligations that are not imposed by existing legal regimes. This would entail domesticating crimes against humanity in national law and taking steps to prosecute perpetrators in national courts. Such steps would stimulate and support the national-level pursuit of atrocity crimes.

The treaty could also include a monitoring body of some kind that would help with preventing crimes against humanity and with State capacity building. The dispute settlement provisions of the treaty could vest jurisdiction in the International Court of Justice relating to disputes between States regarding the interpretation, application, or fulfillment of the treaty.

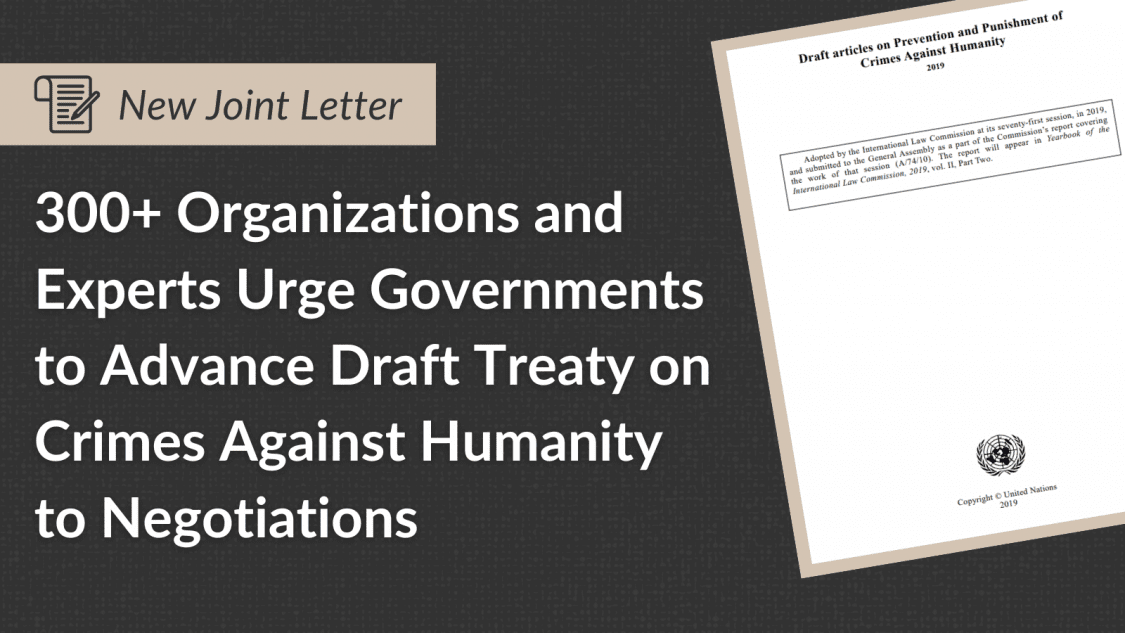

Progress Toward a Crimes Against Humanity Treaty

In 2008, I launched the Crimes Against Humanity Initiative to put the need for a new treaty on crimes against humanity back on the global map. The Initiative is directed by a Steering Committee of global experts, and for the next three years, we consulted more than 250 experts worldwide on the need for and content of a new treaty. We published the world’s first model treaty on crimes against humanity in 2010, which is now available in eight languages. This provided the necessary academic work and momentum for the ILC to take up the topic, and, over a six year period, the Commission developed a set of Draft Articles for a new treaty that was submitted to the U.N. General Assembly’s Sixth (Legal) Committee in 2019. When first submitted to the Sixth Committee, the ILC’s 2019 draft was greeted with widespread support. Nevertheless, the opposition of a small but powerful minority prevented its immediate adoption because the Sixth Committee works on the basis of consensus (meaning that any opposition can prevent a project from moving forward).

For three years, the ILC’s draft stagnated in the Sixth Committee but in 2022, a cross-regional group of States broke the stalemate by submitting a Resolution that would move negotiations forward. After much negotiation, Resolution 77/249 was adopted that provided a two-year process for the Sixth Committee to meet in “resumed session” to discuss the substance of the Draft Articles and the ILC’s recommendation that they be the basis for the negotiation of a new treaty.

Under the auspices of Resolution 77/249, the Sixth Committee has been meeting for the past two years and will decide whether to move to negotiations in October 2024. I am cautiously optimistic about the likely outcome of negotiations this fall, as, due to the hard work of treaty proponents over the past two years, it seemed evident during the April 2024 resumed session that States had not only absorbed the text more fully but have begun to develop positions regarding its provisions and can see the utility and importance of this new convention. Civil society has also moved into high gear, and in 2024, a “Joint Statement in Support of Progress toward a Crimes Against Humanity Treaty” was issued by more than 400 organizations and individuals from around the world.

Overall, more than 70 States urged the adoption of a new treaty in April. Including interventions in the Sixth Committee in 2022 and 2023, this brings the total number of positive States over the past two years to 120, with nine remaining neutral. Notably, however, because Resolution 77/249 only provided a basis to discuss the Draft Articles not to negotiate a common text, no formal negotiations will occur until States decide whether to do so. In October 2024, States will decide whether to proceed to formal negotiations on the document at the Sixth Committee Session.

Credit: FIDH

What Comes Next

Even after two years of comprehensive discussions, the significant support expressed for the new treaty is not enough to move it to negotiations under the framework provided by Resolution 77/249, although it is a promising indicator for the future. To move forward will require skillful leadership to overcome the objections of a handful of States that have successfully used the Sixth Committee’s consensus tradition to block the treaty’s advancement.

One source of this support is a growing consensus that the treaty might gently amend the Rome Statute definition of crimes against humanity to take into account developments over the past 25 years. Proposals from civil society have included adding gender apartheid and forced marriage as new crimes. States also advanced a variety of proposals. Sierra Leone and the African Group support the addition of the slave trade. Nigeria has proposed to include colonialism, and Rwanda suggested adding starvation of a civilian population. There also have been proposals to include ecocide, unilateral coercive measures against civilians, terror-related acts, use of nuclear weapons, exploitation of natural resources, and crimes against Indigenous peoples. Finally, suggestions were made to adjust the definition of persecution. The other source of this support, is, alas, the sorry state of the world today, where crimes against humanity are frequently committed.

In a time of rising authoritarianism and anti-liberal movements, advocacy for a new international treaty can be an uphill battle. Nonetheless, at a difficult time for international justice, with multiple courts seized of atrocity cases, it is incredibly important. Those of us who are engaged in this are determined to put an end to impunity for the perpetrators of these crimes and thus contribute to the prevention of crimes against humanity. Given the significant number of conflicts in the world, and the desperate need of victims for justice, not to mention the imperative of prevention, UN Member States should press hard to advance this critically important new treaty to negotiations in October.

How You Can Take Action

The Crimes Against Humanity Initiative Fund, created in 2008, has supported research, hiring staff, travel, convening meetings, producing promotional materials – including the film Never Again – and other activities related to the work of the Crimes Against Humanity Initiative and the Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute. To date, more than 400 organizations and individuals have signed a “Joint Statement of Support for Progress Toward a Crimes Against Humanity Treaty” mobilized by the Global Justice Center.

The documentary Never Again: Forging a Convention for Crimes Against Humanity (directed by Leila Nadya Sadat, 2017) produced by presents a compelling case for a stand alone treaty. Visit the Initiative’s website to attend an upcoming screening or book a screening.

Mondial is published by the Citizens for Global Solutions (CGS) and World Federalist Movement — Canada (WFM-Canada), non-profit, non-partisan, and non-governmental Member Organizations of the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Government Policy (WFM-IGP). Mondial seeks to provide a forum for diverse voices and opinions on topics related to democratic world federation. The views expressed by contributing authors herein do not necessarily reflect the organizational positions of CGS or WFM-Canada, or those of the Masthead membership.